On issues of inequity, CCSD doesn’t have to go it alone

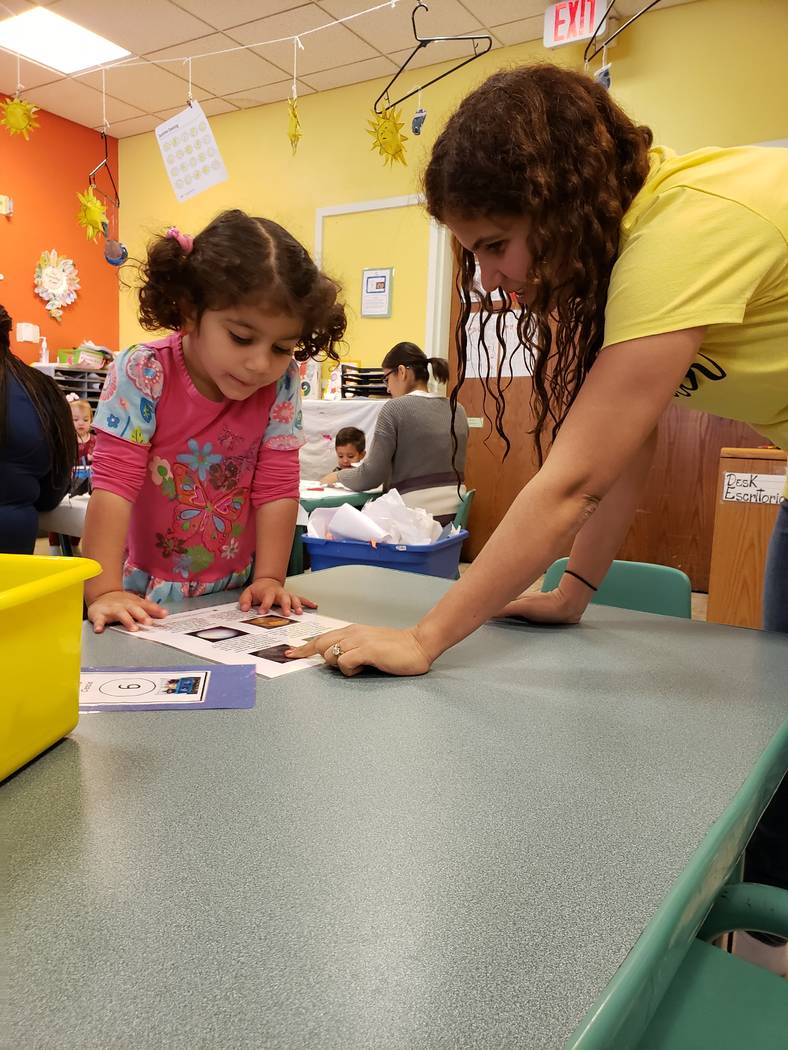

If only all education reporting could be as adorable as the 90 minutes I spent last week in the Family to Family Connection classroom, a soft, sunny space where it’s difficult to turn around without running into a freshly painted model of the solar system.

It’s charming, but it also has a specific purpose, according to Executive Director Dianne Farkas, and that’s to combat inequities that begin at birth for some kids and follow them the rest of their lives.

That topic recently became a focal point for the Clark County School District as well with the release of a report last month from the Superintendent’s Equity and Access Commission that showed African American and Hispanic kids at CCSD have less access to preschool and advanced programs like Gifted and Talented Education, or GATE.

The self-reflection in the report is good, Farkas said. The initiatives that might come from it, like GATE testing for all second-graders, are even better. But in identifying the district’s equity “failure points,” the report missed some obvious ones, according to Farkas.

“By the time we’re talking about GATE, it’s too late,” she said.

One that she’s seen firsthand is transportation. In the Cambridge area, students who reside in a cluster of apartment complexes live just close enough to their schools that bus service is not offered. But their 1.5 mile walk crosses major streets like Maryland Parkway and Flamingo Road — concerning when Metro police recently reported that 36 students have been hit by cars while traveling to and from school in 2019-20 alone.

For parents who work during drop-off or pick-up times, have young children at home or are physically disabled, hungry or otherwise unable to take their children to school have no choice but sending elementary-aged students to make the trek alone. Or, perhaps not sending them at all — the three elementary schools around the Cambridge Community Center report chronic absenteeism rates of eight to 15 points higher than the average for CCSD schools.

Farkas doesn’t expect the district to come up with help for these students, but would like to see a community-based solution in the form of volunteers — possibly from AmeriCorps — who can form what’s known as a “walking bus” to get kids safely to school. Similar programs were started at three other CCSD elementary schools last year through a partnership between UNLV, the city of Las Vegas’ Reinvent Schools program and the Clark County School District’s Safe Routes to School.

The idea is a lot like the Family to Family program itself. Once state-funded, its money ran dry in Recession-era cuts. But by drawing on donors and volunteers, the center has been able to press on as a multifunctional space that serves at times as a birthday party room for kids experiencing housing insecurity, a play area for babies and toddlers and a classroom space for all ages, including adults, teaching topics such as parenting, good nutrition and life skills.

It’s like an auxiliary support system for students, with the kind of boots-on-the-ground perspective that should be invaluable for anyone looking to explore the root causes of inequity, which are more vast and complex than any one report or school district could address. But if Family to Family is any indication, CCSD doesn’t have to go it alone.

“In order to make meaningful improvements in educational success, the day-to-day issues that families encounter need to be understood,” Farkas wrote in a letter to me. “It takes more than a backpack and a new pair of shoes to be ready for school.”

Contact Aleksandra Appleton at 702-383-0218 or aappleton@reviewjournal.com. Follow @aleksappleton on Twitter.