Quality time can beat quantity time, especially for turkey hunts

For many of us, time is the limiting factor when it comes to hunting and fishing opportunity. Even the best laid plans are frequently disrupted by life’s other demands.

If we are lucky, the worst that happens is our planned adventure gets abbreviated rather than cancelled. The key is making the most of what your available time allows, and it doesn’t hurt if you have a friend who can help.

Such was the case with my spring wild turkey hunt here in Nevada. What started out as a week-long hunt on paper came down to a single afternoon after life got in the way. Luckily, I have a turkey hunting addict for a friend.

“I’m on my way back from Arizona,” wrote Kensen Lee in a text. “Did you want to try to hunt your turkey tomorrow?”

Lee, a Las Vegas resident, was returning from the San Carlos Apache Reservation in Arizona where he and his college buddy, Maynard Ely of Reno, had just finished a successful turkey hunt of their own. Fortunately, they weren’t yet ready to call it a day.

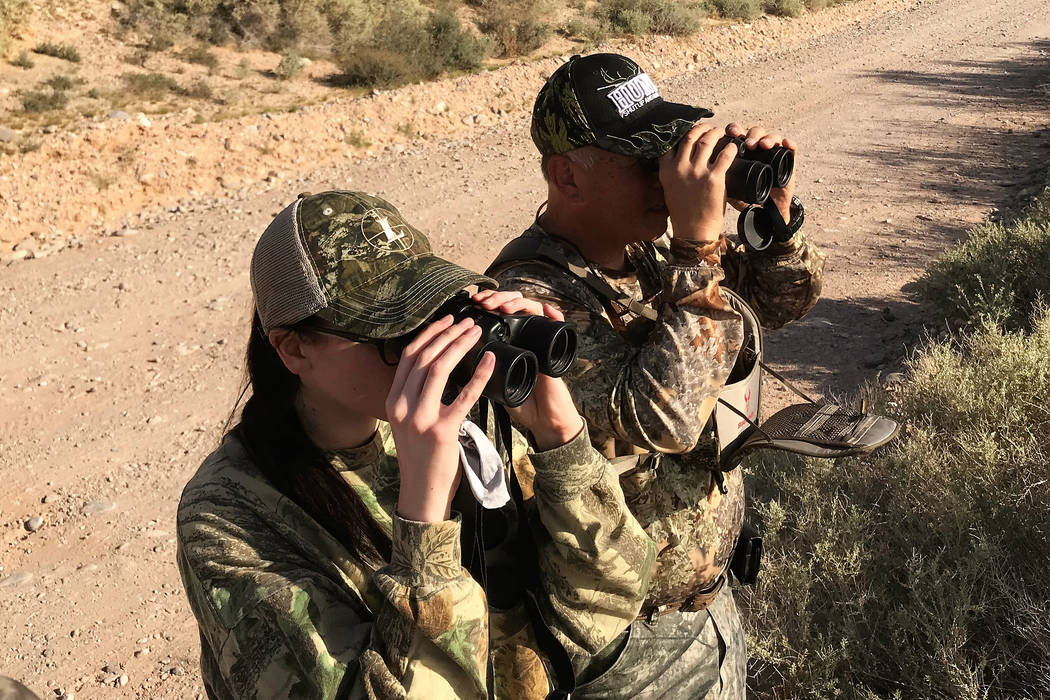

The following afternoon, Calli – my daughter — and I met Lee and Ely at a convenience store in Moapa Valley. From there we drove to a bluff overlooking some fields and started glassing. We soon picked out a handful of birds scratching for bugs. Among them were a couple of mature toms waltzing around in full strut with their tail feathers fanned out wide, body feathers puffed up tall, and their wings held out in an arc along their sides.

Though the birds weren’t very vocal, we did hear a gobble or two. And that was just enough to put us into serious hunting mode.

Since it was late in the day, our goal was to intercept the birds on their way back to their roosting trees. Slipping through the brush we made our way to an overgrown fence line where we donned our camouflage face nets. Suddenly Ely, whispered to get my attention and pointed toward a nearby field. There in the field was a gobbler and a pair of hens.

A close look through the binoculars showed he was a mature bird with a heavy, long beard that drug on the ground as he walked. “He’s a good bird!” I whispered.

Leaving Calli, Lee and Ely on one side of the fence, I crawled through the overgrowth to reach the far side. There I sat down with my back against the trunk of a large tree and began waiting for the birds to make their way back to their roost.

Turkeys are not a stupid bird and have a reputation for detecting the slightest movement a hunter makes, but it seemed like I slipped in undetected. Then, keeping my own eye on the strutting gobbler, I sat as still as possible and waited.

Time ticked by, but neither the gobbler nor the hens moved in my direction. They just seemed to hang up about 80 to 90 yards out, far beyond shotgun range. Then at some point they just moved to the left and out of sight behind some old farm equipment. Every now and then, I heard a hen cluck, so I knew the birds were still there. Hope remained.

Then about 6:30 p.m., with the end of my hunt growing closer, turkeys just started showing up in the field. They came in groups of twos and threes, walking clear of heavy brush and into the field. Their numbers quickly grew to 41, and about half of those were toms. Many were good mature birds, and I would happily take any one of them.

At one point, a young tom looked intently my direction for several minutes. Then he turned and seemed to walk away, but he quickly wheeled around and looked my way again. He repeated this several times. It was as if he were trying to goad me into moving. When that was unsuccessful, he simply faded into the growing flock.

That proved to be about the closest encounter I would have that afternoon. Even with a field full of birds, they all remained well out of shooting range. With two minutes of legal shooting time left, I unloaded my shotgun and walked over to where my friends and Calli were waiting.

“Wasn’t that a great hunt?” Lee exclaimed as I walked up. And he was right. It wasn’t long, but it was indeed a great hunt.

Freelance writer Doug Nielsen is a conservation educator for the Nevada Department of Wildlife. His “In the Outdoors” column, published Thursday, is not affiliated with or endorsed by the NDOW. Any opinions he states in his column are his own. Find him on Facebook at @dougwritesoutdoors. He can be reached at intheoutdoorslv@gmail.com