Class teaches dogs how to avoid rattlesnakes

Tessie was an inquisitive dog with a great nose for game birds. If there were quail or chukar in the neighborhood, she would sniff them out and let me know where they were holed up. The smallish black Lab even pointed, though as a retriever her point was a bit on the rough side by pointing dog standards.

But Tessie knew little about snakes, and early one cold November morning came close to learning the hard way about the business end of a Mojave rattlesnake I had stopped to get a closer look at. Luckily, the cold temperature made the snake quite lethargic because Tessie soon ran over to see what held my attention and began dancing excitedly right on top of the snake while looking at me for direction.

By the time I managed to get Tessie safely behind me, Mr. Mojave was wide awake and sounding his displeasure at having his beauty sleep interrupted.

In the years that followed, I thought often about that encounter, counted my blessings and wondered how one might go about teaching their dog to recognize a snake as something to be left alone. Then someone told me about rattlesnake avoidance training, something John Potash, owner of Reno-based Get Rattled, does for a living.

“Essentially, we train dogs to recognize and avoid the sight, sound and smell of rattlesnakes,” Potash said during a recent pet event in Las Vegas. “Unlike a person that you can say, ‘Hey, stay away from these, they’re dangerous,’ dogs take a little bit more to convince. Plus, a dog’s natural sense of curiosity tends to put them in harm’s way.”

While a dog’s strong sense of smell is one of the things that makes it such a valuable hunting companion, it can quickly lead to trouble with snakes. Outdoorsmen often walk past snakes without realizing it, but a dog’s nose will lead it right to the snake and its hiding place.

One of the challenges with dogs and snakes is that dogs don’t always associate the snake with the bite when they are bitten.

“So a lot of dogs will get bitten time and time and time again,” Potash said.

To illustrate his point Potash told me about one customer who reported that his 10-year-old dog had been bitten by rattlesnakes 11 times, so he finally brought the dog to a training session.

Potash uses an aversion training technique with electronic collars to reinforce the idea that snakes are bad business.

“By doing the e-collar training, it’s instant negative association,” he said. “So the dog puts it together right away. And then by doing it in the different aspects, like I mentioned, they can see it (the snake) and they get a correction, they can hear it get a correction, smell it get a correction. Then they know instantly that ‘OK, this is something I don’t want to mess with.’”

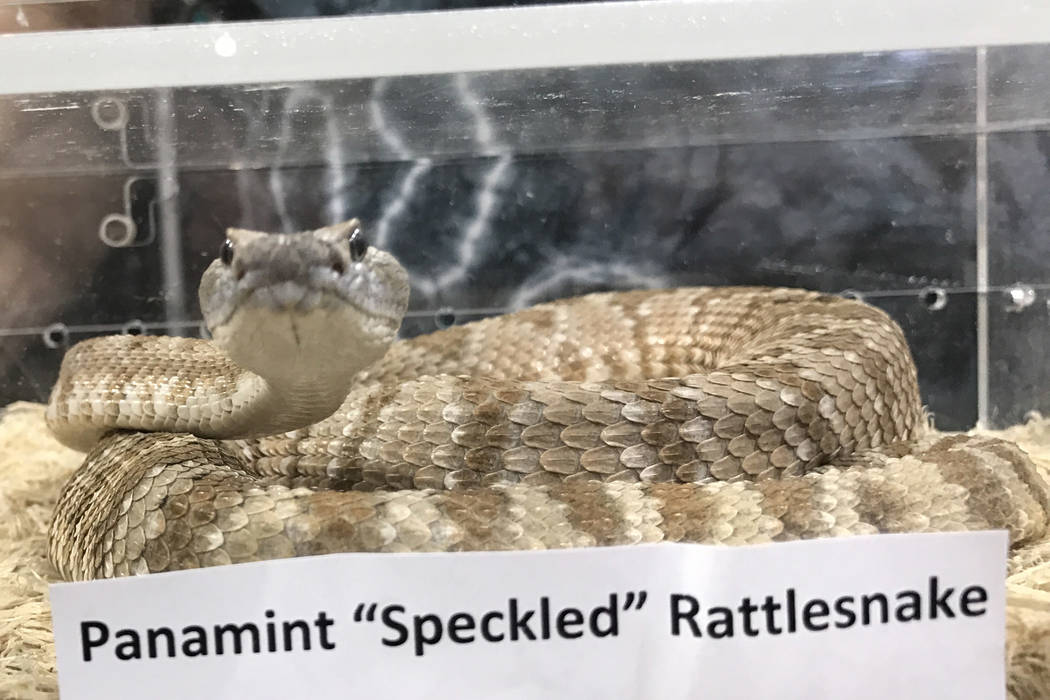

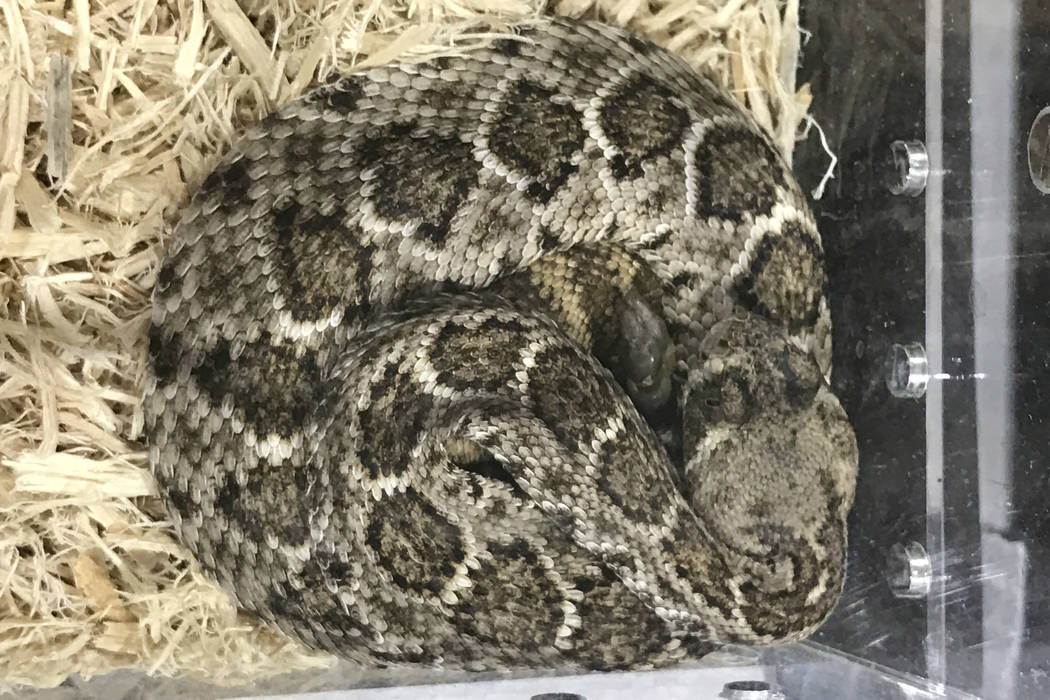

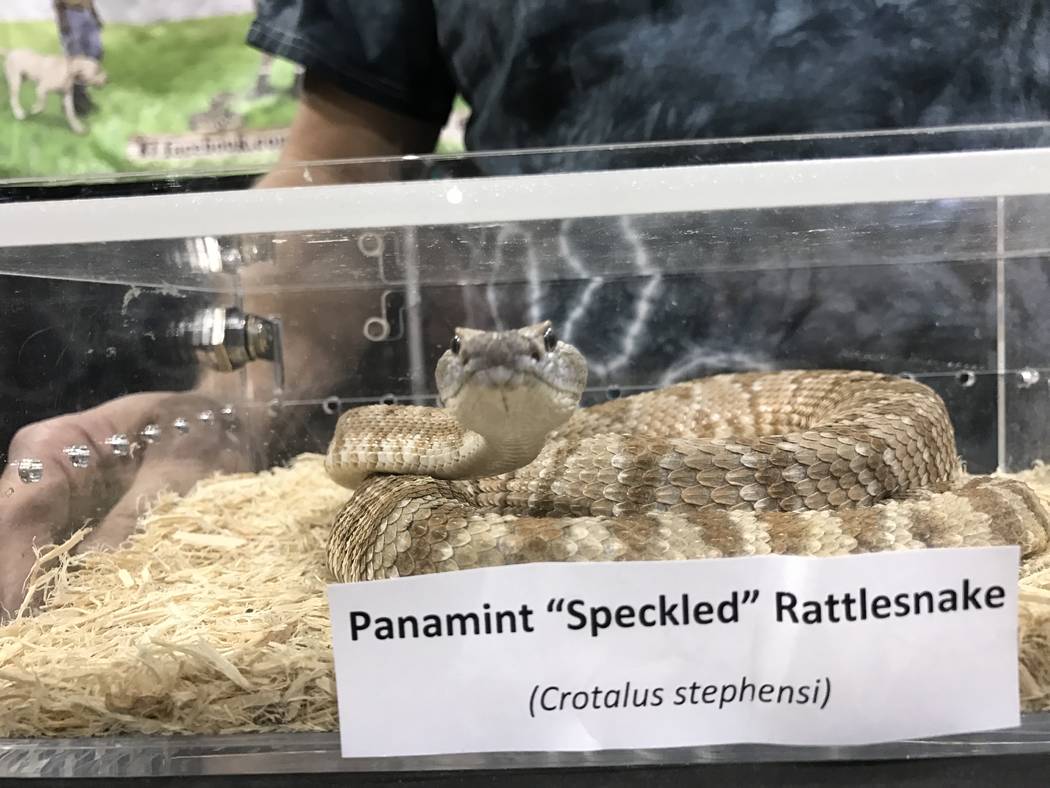

Potash uses live snakes and multiple stations in his training program. The first station involves a live rattlesnake (its venom ducts have been surgically removed) on the ground so the encounter is as natural as possible. Once the dog shows a sign of recognizing the snake’s presence — such as the ears going up, the tail wagging or turning to face the snake — the trainer gives the dog the e-collar correction. The dog is then walked away quickly so it learns that’s the correct response.

Another stage uses a live rattlesnake inside of a cage where it can hide and the dog can smell it without seeing it. In this instance, the snake still has its venom sacks so it can produce venom in case a dog can actually smell the venom and begin to associate that with the animal.

Potash recommends that anyone who takes their dogs outdoors for any recreational activity or who lives on the outskirts of town send their canines to rattlesnake avoidance training. Rattlesnakes can be found in areas throughout the valley with the right kind of habitat. One series of hiking trails in Henderson is marked with signs warning that rattlesnakes often can be found in that area.

A training class will be held from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Saturday at the Bark in the Park event at Cornerstone Park in Henderson. The cost is $85 per dog. For more information, go to getrattled.org.

Freelance writer Doug Nielsen is a conservation educator for the Nevada Department of Wildlife. His “In the Outdoors” column, published Thursday in the Las Vegas Review-Journal, is not affiliated with or endorsed by the NDOW. Any opinions he states in his column are his own. He can be reached at intheoutdoorslv@gmail.com.