NFL draft: How an afterthought became a cultural phenomenon

NEW YORK

This all happened because of Stan Kostka.

He was a star running back when leading the University of Minnesota to a perfect season in 1934. His nickname was King Kong, and all 11 NFL teams wanted to sign him.

He wanted to get paid, so he held out for the highest bidder. Nine months later, even after he lost a bid to become mayor of Inver Grove Heights, Minnesota, he received $5,000 to become a member of the league’s team in Brooklyn.

King Kong lasted just one season, but the NFL wasn’t going to allow such a storyline to repeat itself. The solution: an amateur draft.

Las Vegas, now home to the Raiders and Allegiant Stadium, was scheduled to host its first draft Thursday through Saturday. But those plans were interrupted by the coronavirus pandemic, as the draft and all its expected splendor were canceled in Southern Nevada.

Instead, the three-day event will now be held remotely over its seven rounds, in which teams will make picks from the homes of those team officials making the selections.

Zoom. It’s a whole new world. But the essence of the draft remains the same.

“It ultimately boils down to hope,” said Peter O’Reilly, the NFL’s executive vice president for club business and league events. “That’s what is at its core. It’s a fraternity, a kind of pilgrimage of those who follow the NFL so closely throughout the season. Those who live and breathe it, so it’s nice after a little break following (the season). It’s a chance to come back together.”

There won’t be such a journey of fans this year, no hundreds of thousands of folks partying up and down the Las Vegas Strip, no vast gathering of those wearing jerseys and awaiting their favorite team’s selections.

No — gasp! — booing of commissioner Roger Goodell, at least not in such an open and public setting, which, until a few years ago, wasn’t even a consideration.

In the beginning …

First, some context.

Owners in the mid-1930s, led by Bert Bell of the Philadelphia Eagles, wanted to increase the competitive parity throughout their league so that the Stan Kostkas of the world couldn’t merely decide where to play based on dollar signs or failed mayoral campaigns.

Translation: Let the worst team from the previous season have first opportunity at the best player. The vote was unanimous.

The first draft was held in 1936 in a Philadelphia hotel owned by Bell, later a Hall of Fame inductee who would become the league’s commissioner from 1946-1959. His team, a forgettable 2-9 the previous season, held the first pick.

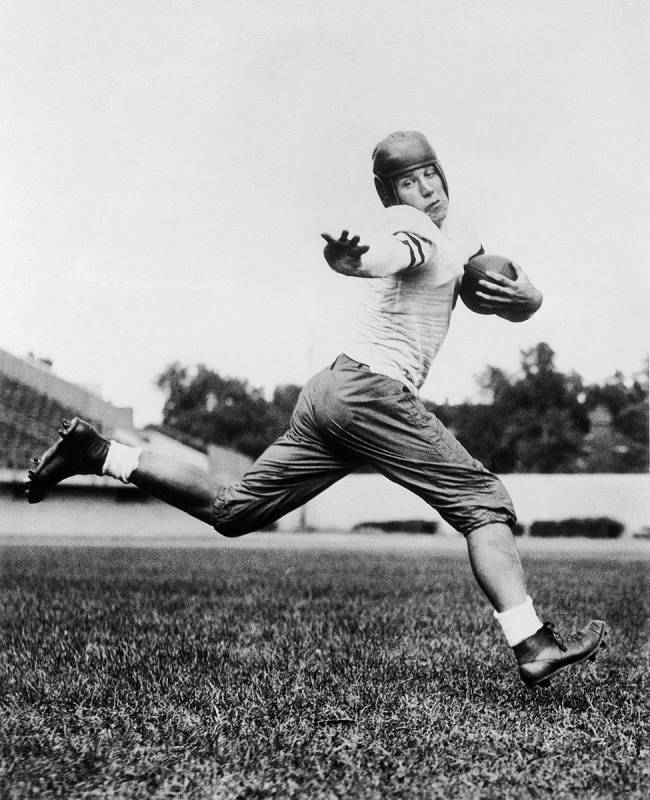

It chose Jay Berwanger, a halfback from Chicago University who was also the first recipient of what became known as the Heisman Trophy. Berwanger decided not to play professionally and left football.

Still, the draft had been established. And away the thing went.

Certain aspects have been revised since its creation. Notably, the draft has lasted as many as 30 rounds to as few as seven (beginning in 1994).

Player scouting began in 1946, but the competition for players did not become so cutthroat until the fourth and most successful version of the American Football League formed in 1960. That year 75 percent of the NFL’s first-round draft choices chose to sign with the rival league, which stole college players and even hid available seniors.

Such competition for the best talent went on until the leagues merged. Their respective championship games would eventually become the Super Bowl.

Think about it: In 1960, there was no credit-card calling. Teams would feed quarters into a telephone to ask college coaches who were the best draft prospects they had coached or competed against.

There also wasn’t a time limit between picks. Dallas, the first team to use computers for evaluating talent, waited six hours to make a second-round selection during the 1964 draft while checking on the health of defensive back Mel Renfro.

During the delay, Packers coach Vince Lombardi walked by the Cowboys’ draft table and asked: “What happened? Did your computer break down?” Probably. The fancy laptops of today were instead monstrosities from IBM.

How much interest was there in those drafts? Judging by the media coverage, not much. It’s estimated five or so media members covered the 1960 draft. Now, more than 1,700 credentials are approved annually.

“We didn’t have high-tech (information),” is how Gil Brandt, Hall of Famer and former vice president of the Cowboys from 1960-88, described those early days. “What we had to do was understand what a football player was made of. Things like strength, explosion, competitiveness, agility and balance.

“Then we’d come up with things that were specific to positions. Mental alertness was high for quarterbacks while strength and explosiveness had to be high for defensive linemen. We had to put a value on what we were looking for … It was never a bad thing to be too smart.”

As decades passed and technology improved, the draft got bigger and bigger. No advancement was more prodigious, however, than when television became involved.

“(The late) Chet Simmons, then with ESPN, approached commissioner Pete Rozelle in 1980 and said they wanted to televise the draft,” O’Reilly said. “And the commissar said, ‘Why would you want to do that?’ ”

Thinking back, maybe because Simmons saw how the obsessive nature of fans could eventually deliver big ratings. Last year, there were more than 76 live hours of draft week coverage. Telecasts combined to reach more than 47.5 million viewers, up 5 percent from 2018.

Held at the base of the Cumberland River adjacent to Lower Broadway in Nashville, Tennessee, more than 600,000 attended over three days. The location of that draft was the continuation of a new-age philosophy by the NFL that began in 2015.

Start spreadin’ the news is right, the draft had left New York.

Big Apple party

It began in 1965, the league’s belief that holding the draft in the city that never sleeps was in everyone’s best interest. It went that way for 50 years.

Five decades of Jets fans booing their team’s every pick. Summit. Gotham. Belmont. Essex. Americana. Hilton. Roosevelt. Waldorf. Marriott. Year after year, different hotels welcomed the draft.

Early on, players located on higher floors would learn which team selected them by waiting for the dial up to ring. It was as if room service was confirming a dinner order.

Much later, things got real fancy. Radio City Music Hall is nicknamed the Showplace of the Nation, sitting on the 1200 block of Avenue of the Americas and within Rockefeller Center. The draft was first held there in 2006, gaining in spectacle each passing year.

But one of the showpieces of Midtown Manhattan is also home to the famed Rockettes, and a scheduling conflict in 2014 between the NFL and the dance company meant the draft was moved from April to May. Which meant the league felt it best to consider other potential locations. Even ones outside.

“The lines were around the corner and it was a red-carpet, star-studded affair at Radio City,” said Stephen Nichols, Sports/Newsroom director for SiriusXM Radio in Manhattan. “It was great for the excitement part of it, but eventually the league wanted to get a little taste of what other (cities) could do.

“The NFL has fans all over the country, all over the world. Obviously, we’ve seen the kind of buzz a draft can create in different places. It has become bragging rights for those who can now get it. There’s nothing like it, the hope it creates.”

Chicago (2015 and 2016) as draft host was followed by Philadelphia, which was followed by Dallas, which was followed by Nashville, which was supposed to be followed by Las Vegas.

Dallas was the first city to host the draft inside an NFL stadium. The others were a bit more creative.

O’Reilly and Bears chairman George McCaskey did a polar plunge into Lake Michigan when 150,000 folks showed up for draft festivities at Grant Park in 2015; Philadelphia used its Museum of Art, with the “Rocky” statue, as a backdrop to the league’s first outdoors draft; Nashville had its honky-tonks alive and rocking.

“I’d be lying if I said we believed staging the (draft outdoors) had this much potential,” O’Reilly said. “When we moved it from New York, there was significant interest. But even then, it was still in our minds and those of different cities that it would be a theater event. But doing what we have (outside) has certainly outdone our expectations.”

They also believed the next city in line would surpass all others for pomp and circumstance and levels of celebration.

Alas, a pandemic put such plans on hold.

Leaving Las Vegas

You can rank the NFL’s most important annual dates as following:

Super Bowl.

Opening weekend.

Draft.

Las Vegas was to be the first NFL draft held in the Pacific Time Zone, set for that enviable prime-time television spot on Thursday that features only the first round. It’s a tradition that began in 2010.

Instead, there will be no boat rides for prospects to the red carpet on the Fountains of Bellagio. No selection stage at Caesars Forum and next to The Linq Hotel. No daily live concerts. No draft experience for fans.

The benefits of hosting a draft, of drawing thousands and thousands of tourists and integrating them into the community, can’t be overstated. But the town that does everything big is now dark, meaning Las Vegas must wait for another time to welcome those football fanatics hoping to hit the jackpot. Be at a casino or with their favorite team’s selections. Or both.

The draft site for 2022 and 2024 has not been determined, and there is every reason to believe the NFL will make up for this year’s cancellation by awarding Las Vegas one of those years. Goodell said as much in March, while also mentioning in a statement the city as a site for a future Super Bowl.

This was O’Neil in November, long before the coronavirus was a reality, busy planning to direct yet another outdoor draft: “We need to do right by Las Vegas. The biggest response we got from fans watching on TV last year was that as they flipped through channels, Nashville looked like it was New Year’s Eve. So even those who weren’t draft fans stopped and watched.

“How do we have that in Vegas? The bones are there for doing something very special.”

All of that now will have to wait.

History, for the moment, has changed course. Come Thursday, a different type of draft war room takes the lead.

Wonder what Bert Bell would have thought about Zoom.

Contact columnist Ed Graney at egraney@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-4618. He can be heard on “The Press Box,” ESPN Radio 100.9 FM and 1100 AM, from 7 a.m. to 10 a.m. Monday through Friday. Follow @edgraney on Twitter.

NFL draft history

Key dates

May 1935: Owners unanimously approve amateur draft.

February 1936: Eagles make halfback Jay Berwanger the first pick in draft history.

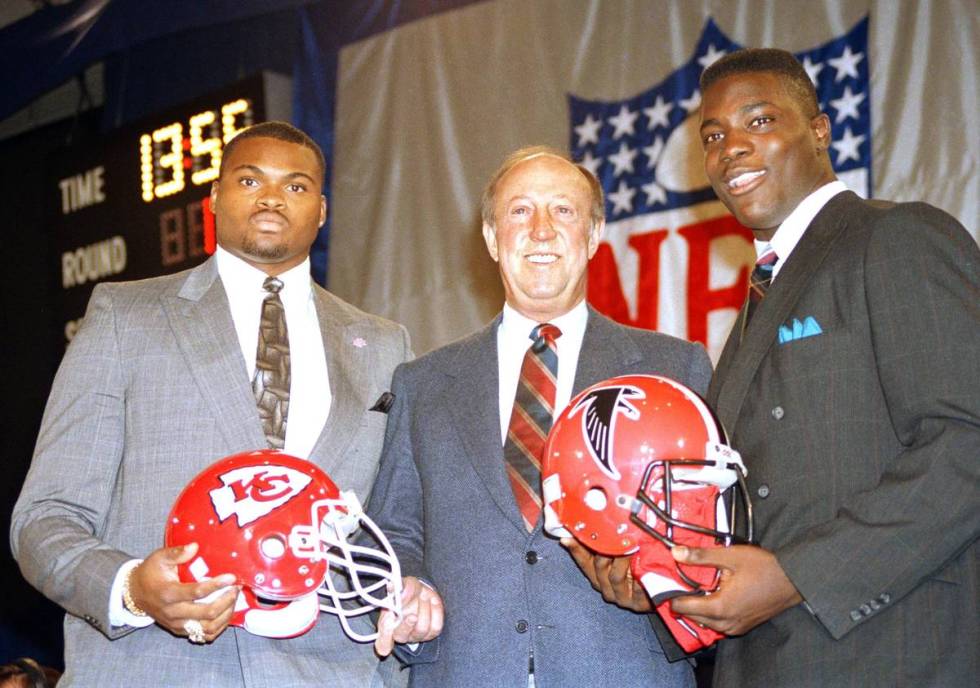

June 1966: NFL and AFL merge, agreeing to a "common draft," ending bidding war for college players.

April 1980: Draft is televised for the first tine (ESPN).

April 2015: Draft set in Chicago, ending a streak of 50 years of being held in New York.

April 2017: For first time, draft is held outside (Philadelphia).

April 2019: Over a three-day span in Nashville, more than 600,000 attend draft.

March 2020: Effects of the coronavirus lead to draft being canceled in Las Vegas.

April 2020: League announces this year's draft will be "fully virtual" as team facilities remain closed.