A look back at the history of NFR — PHOTOS

Las Vegas began hosting the National Finals Rodeo in 1985, but how did it get here?

The rodeo’s transition away from its Oklahoma City home, where the event had been hosted for 20 years, was anything but pretty.

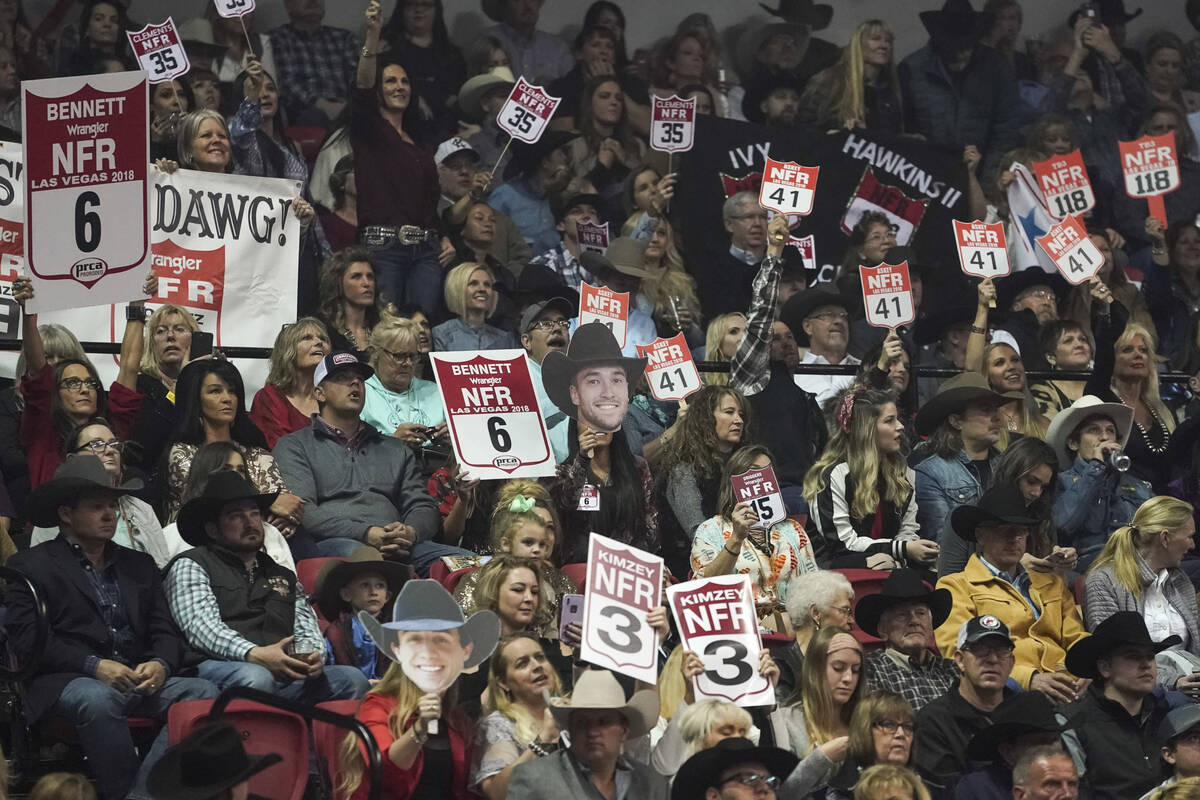

Much like how NFR boosts Las Vegas’ economy today, Oklahoma City’s economy got an $8 to $10 million dollar boost annually from the rodeo (about $22 to 24 million today adjusted for inflation). The rodeo sold out 117 consecutive performances from 1973 to 1984, the year Las Vegas proposed the move to Sin City, and the town was less than pleased about the idea of losing their beloved cowboy tradition.

Herb McDonald, director of the event management company and NFR sponsor Las Vegas Events, told the Review-Journal during the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association’s negotiations “It’s like trying to move the Tournament of Roses from Pasadena.”

Former President of the Oklahoma City Chamber of Commerce Ed Cook called Las Vegas “scavengers.”

“Las Vegas, they’re scavengers. They didn’t want the rodeo when it wasn’t worth anything. Now they’re coming in and trying to flat buy it. We don’t think that’s fair,” Cook said.

On Dec. 13, 1985, the PCRA voted to move the rodeo after the Las Vegas Convention and Visitors Authority promised the PCRA the city would cover the entire budget of the rodeo for the next five years. Las Vegas also had more space, with 44,000 more hotel rooms than Oklahoma City at the time and the Thomas & Mack Center holding 5,000 more fans than Oklahoma City’s venue.

Casino visionary Benny Binion also helped bring NFR to Las Vegas by being one of its main boosters. Binion was known for paying cowboys’ entry fees to the rodeo, earning him a standing ovation at the first-ever Las Vegas NFR and the honor of being PRCA’s Man of the Year in 1985.

As the Associated Press put it, paraphrasing Dave Baldridge, director of media relations for the PRCA, “Twenty years of tradition just cannot compare to the promise of more prize money,” which was another perk the LVCVA promised the association in their rodeo bid.

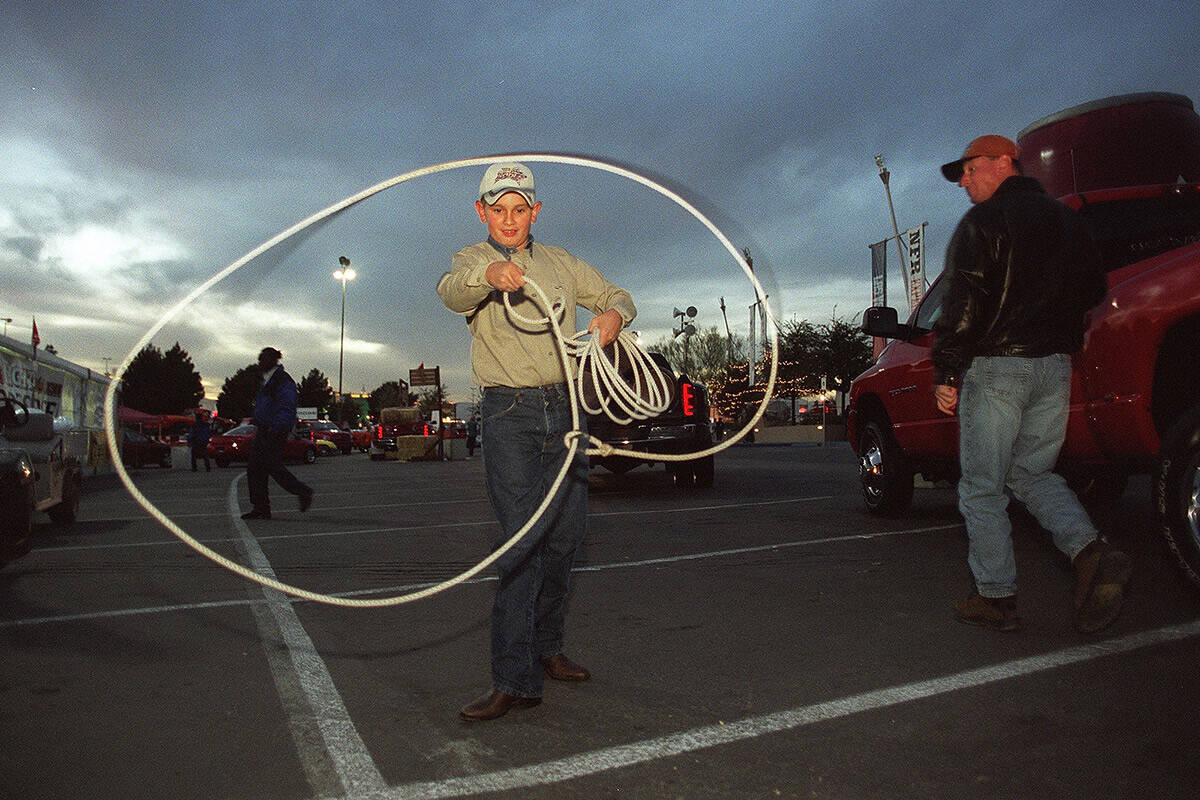

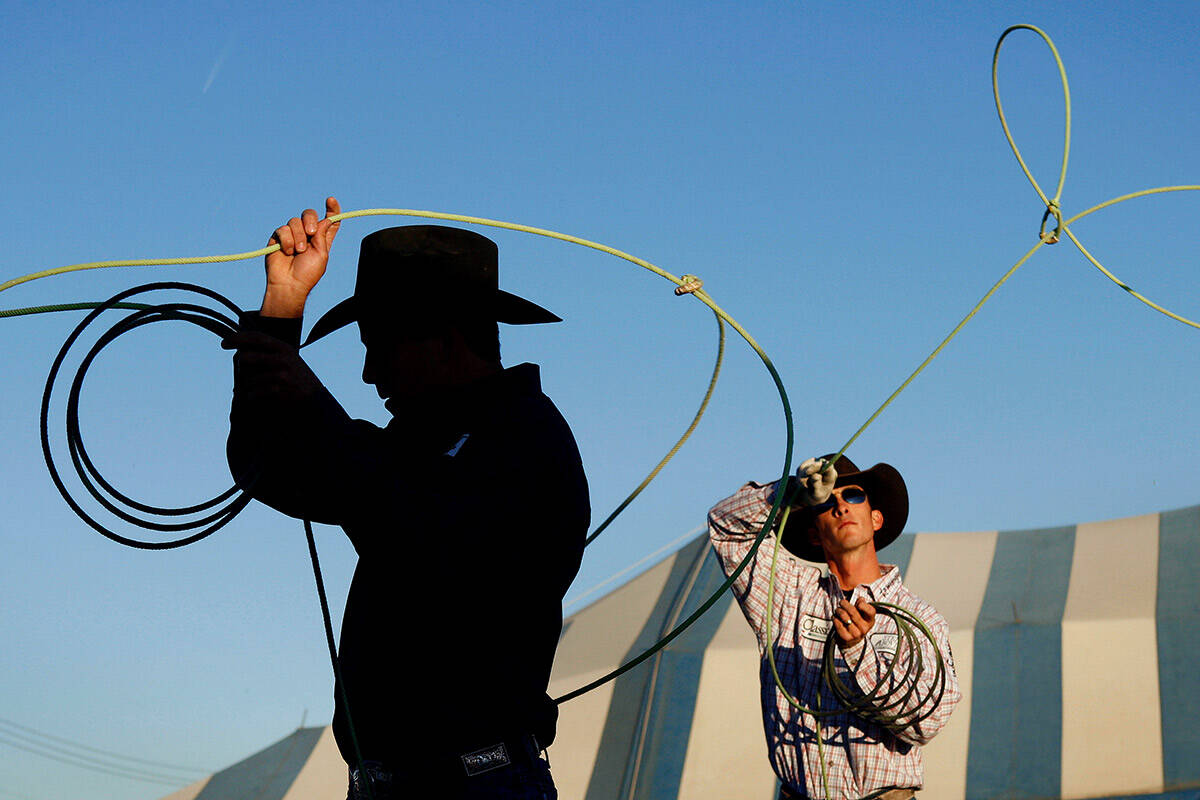

Young competitors didn’t care about tradition, either.

“We have a whole new generation of young cowboys reaching national prominence,” Baldridge said. “Certainly, they would not share the strong ties with Oklahoma City that some of the older members would.”

But, not everyone was happy about how the rodeo got approved.

The LVCVA violated the state Open Meeting Law to approve the city’s decision to pay for the rodeo after board members approved funding in an emergency meeting over the phone. Former Clark County Commissioner and LVCVA board member Manny Cortez called out former LVCVA Executive Director Frank Sain for the impromptu vote.

Sain defended his decision, saying “I realized we were bordering on that but we had a choice — respond within 45 minutes to an hour or forget about it and lose (the bid) by default.”

UNLV fans weren’t happy, either.

The Rebels weren’t excited about sharing Thomas & Mack Center with the rodeo. Bill Morris, a UNLV backer who was instrumental in the T&M’s construction, said the facility was originally built for UNLV athletics.

“Now, they’re keeping everyone, including the Lady Rebels, out for the National Finals Rodeo,” Morris told the Review-Journal in February 1985.

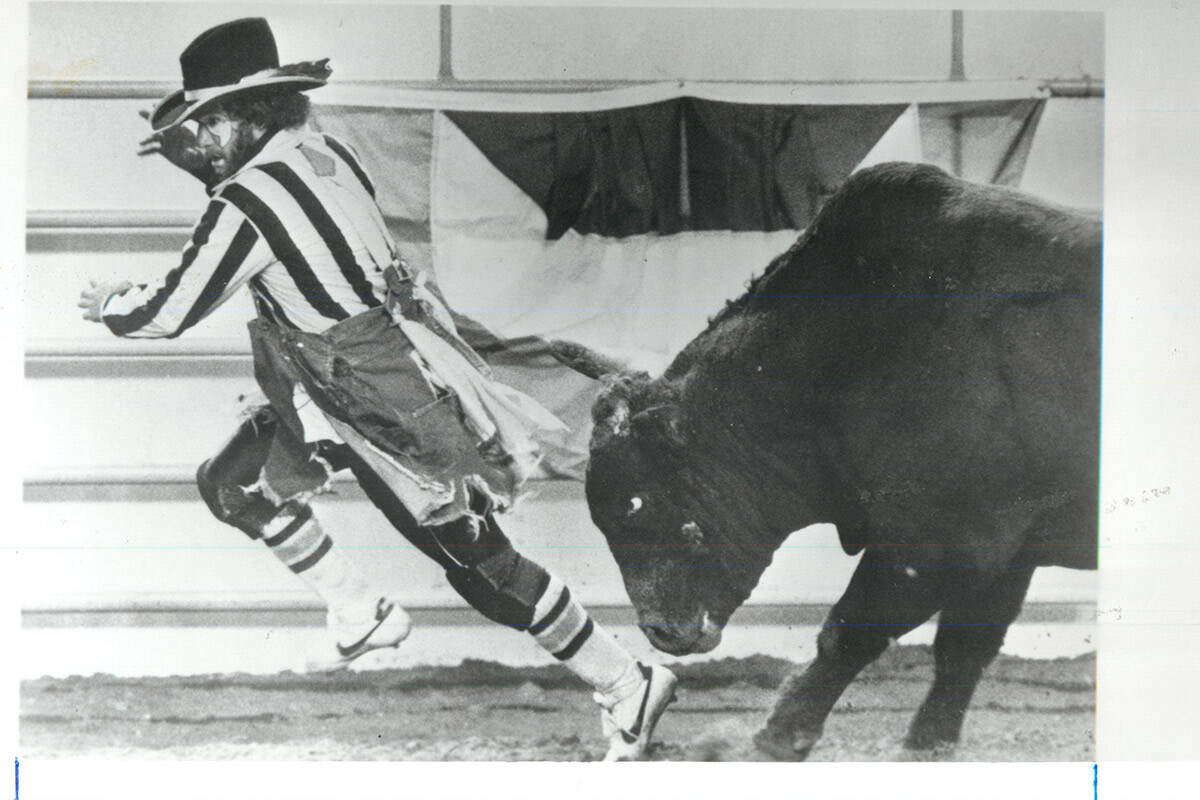

The greatest concern was the rodeo’s set up and take down. The rodeo only lasts 10 days, but moving cow poop in and out would take around three weeks.

Dennis Finfrock, who turned T&M from a basketball-only venue into a multiuse facility, promised Rebels basketball coach Jerry Tarkanian that the rodeo would not interfere with Rebels’ games.

In Finfrock’s 2009 obituary, Review-Journal reporter Jeff Wolf wrote “Without Finfrock’s vision, Las Vegas might not be hosting the National Finals Rodeo.”

Ten months later, the cowboys came, and so did their cash.

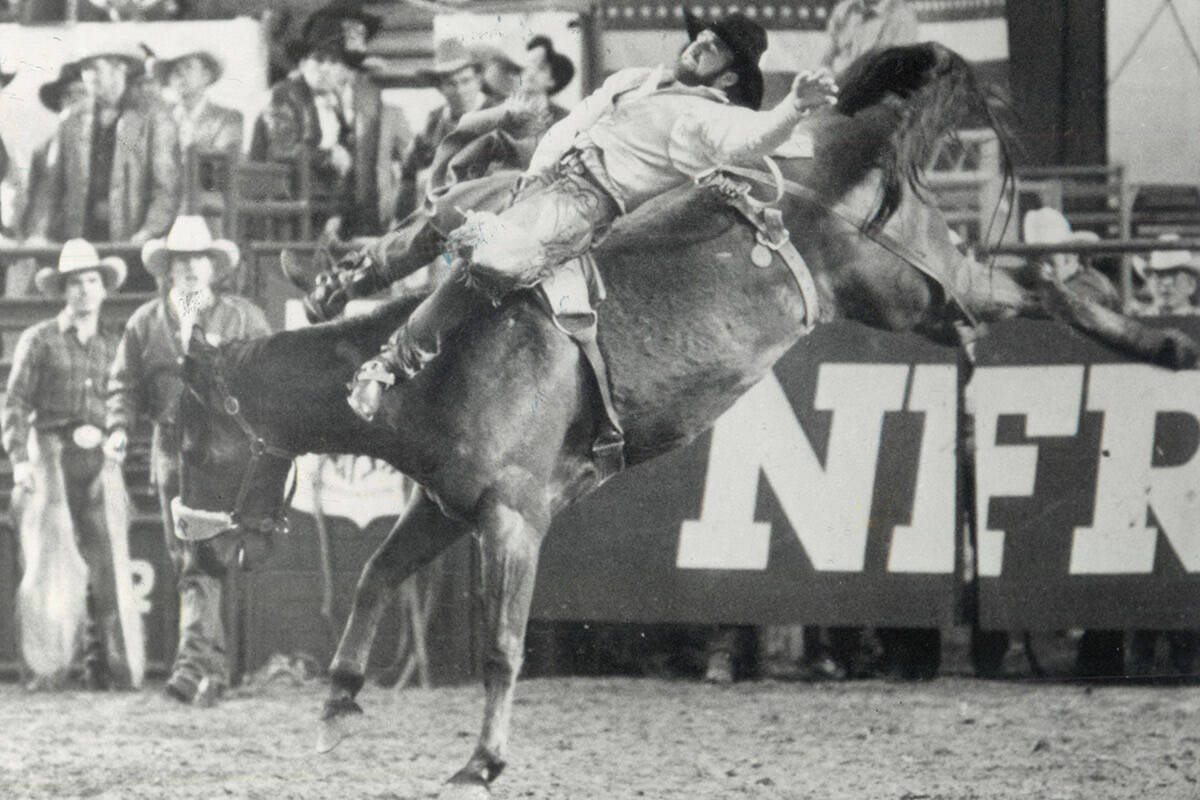

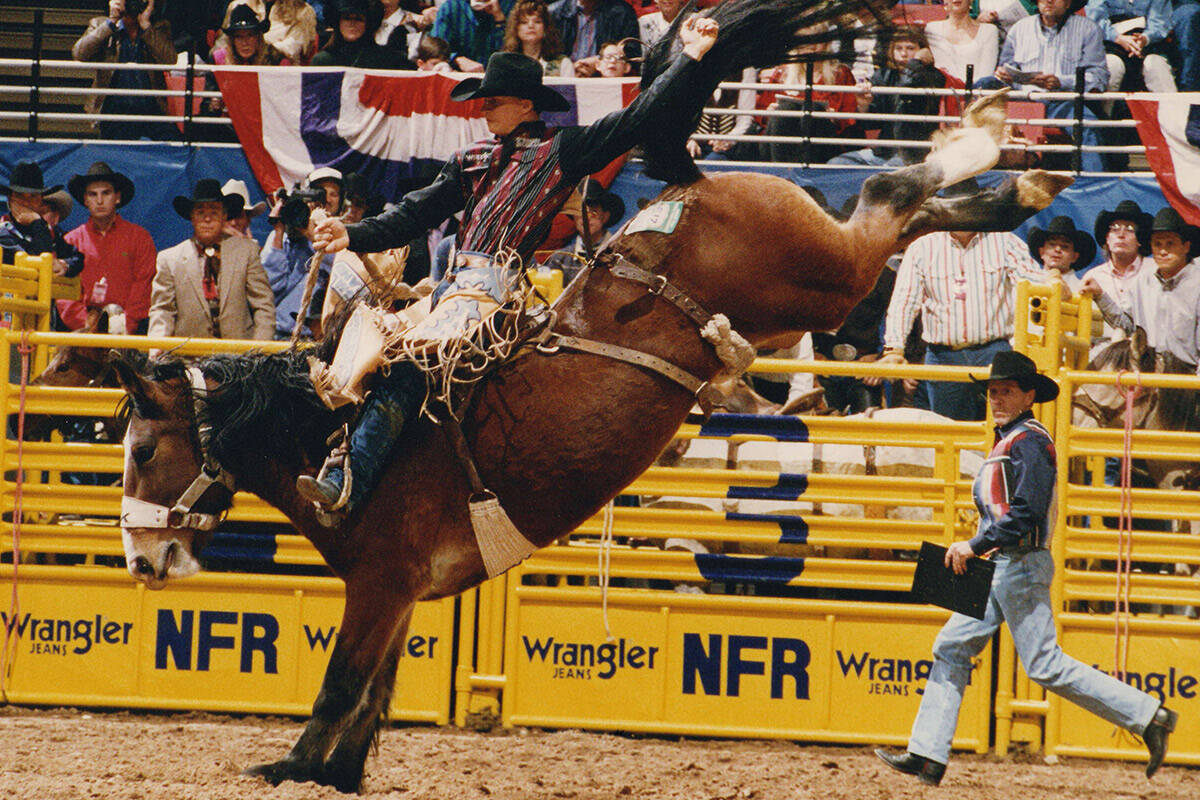

The rodeo, as anticipated, brought the Las Vegas economy an estimated $43 million. McDonald said between 18,000 and 20,000 people came to Las Vegas for the event. T&M attendance was 142,800, with all 10 days of the rodeo sold out. Bareback rider Lewis Field was the finals all-around champion.

Bareback rider Shawn Davis told the Review-Journal “In all of my years, this might just be the most exciting National Finals I’ve ever been to.”

Review-Journal sports reporter Rick Spiritosanto said what made NFR in Las Vegas stand out from its Oklahoma City era was the money put into it.

“It was money that wooed the rodeo here and it was money that provided what many considered to be the fiercest competition ever.” Spiritosanto wrote. “Competition was keen and the world of professional rodeo benefited.”

And the rest is history.