I need to keep him focused. I need to keep him focused. I need to keep him focused.

Tim Hallmark’s mind races in unison with his heart.

He must act faster still: Sweat and blood commingle on his fighter’s shoulders, the big man’s barn-sized trapezoids swiftly turning barn red.

“Don’t mention the blood,” Hallmark thinks to himself, though it’s hard to think at all in here: The crowd of 18,000-plus is making so much noise, it’s as if larynxes have been swapped with tornado sirens.

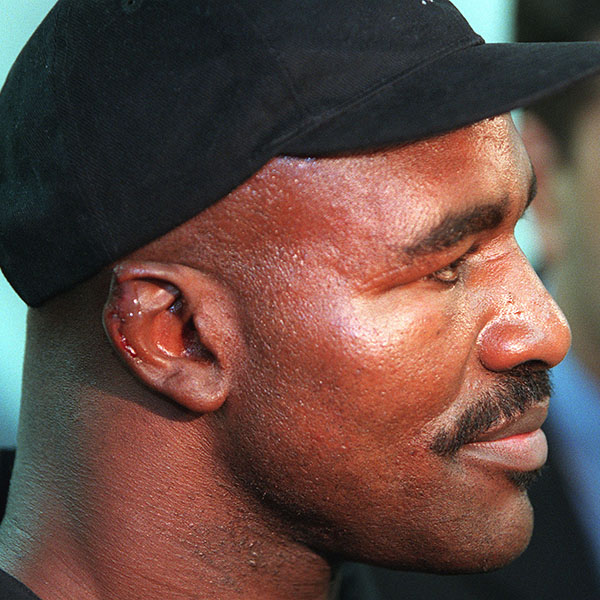

On the canvas somewhere: a hunk of cartilage formerly part of the ear of Evander Holyfield, the heavyweight champion currently fuming before him, pistoning his legs into the ring as if attempting to stomp out a fire of another man’s creation.

The abused glob of flesh wouldn’t be found until hours later.

It had bite marks.

“I looked him straight in the eyes,” recalls Hallmark, one of Holyfield’s trainers, a chiseled-from-granite Texan who, at age 67, can still do more pushups than you. “I didn’t say a thing about his doggoned ear. I didn’t tell him the sucker was bleeding because I knew that would have freaked him out.

“I said, ‘Hey man, that’s no big deal,’ ” Hallmark continues, his voice as punchy as the fighters he’s trained for four-plus decades. “ ‘Forget about that and keep your thoughts, keep your eyes on your job, man.’ I kept saying that: ‘Keep your eyes on the job.’ ”

I didn’t say a thing about his doggoned ear. I didn’t tell him the sucker was bleeding because I knew that would have freaked him out.

Tim Hallmark

Here’s the thing: Evander Holyfield hails from the always-keep-your-head-on-a-swivel Bowen Homes Housing Projects of Atlanta, Georgia. There’s a simple rule of the streets in those parts, at least in Holyfield’s mind: If someone does something to you, you do it right back to them — only harder, way harder.

Else they just might try to do it again.

And so Holyfield fully intends to reciprocate.

Bite me. I bite you.

But Hallmark gets through to him somehow, gets through the fog of adrenaline and vengeance and all these raised voices engulfing Holyfield every which way in a cocoon of full-throated roars.

Keep your eyes on your job, man.

Holyfield regains his composure; the bell rings; action resumes.

Then Mike Tyson does it again.

Shortly thereafter, the then-biggest fight in the history of Las Vegas — a city with a boxing pedigree as outsize as Tyson and Holyfield’s combined $65 million payday for the clash in question — comes to a sudden, crashing end evocative of a freight train jumping its tracks and plowing into the guts of a nuclear power plant, the fallout toxic.

It was supposed to be an epic rematch between polar opposites, the whole good versus evil thing spelled out in all caps: a highly devout man of god going at it with the sport’s greatest intimidator, a sneer incarnate with devilish tendencies; a crazy-lucrative, celebrity-heavy showdown between a guy who prays even more often than he punches people in the face and this frothing hunk of muscle and sinew and anger who once threatened to eat an opponent’s children, who embraces the bad guy role right down to his black trunks — even if, deep inside, he was really only a bully because he himself had been bullied so harshly growing up in his native Brooklyn, New York.

Tyson was feared, but also admired, a snarling symbol of the American dream as realized by a nightmare in the ring.

“He was something that every bad boy, every human could identify with, being that little kid on the street, a guy that just would not take no more,” says 90-year-old boxing maven Don King, who promoted the fight. “He came from the streets. No hand-me-downs, no recommendations, no nothing. He fought his way up to the top.”

And it was at the top that Tyson met Holyfield, their megafight a way more sizable and significant event than just a heavyweight championship boxing match between two superstars of their day.

Boxing’s not the biggest sport in terms of popularity — wasn’t then, isn’t now — but it’s long boasted events capable of eclipsing the bubble of sports to begin with, these enduring pop culture moments that unfold in real time among a galaxy of stars seated at ringside.

It’s theater, it’s drama, and yet it’s real — as evidenced by all the bruises and broken noses and bleeding scalps.

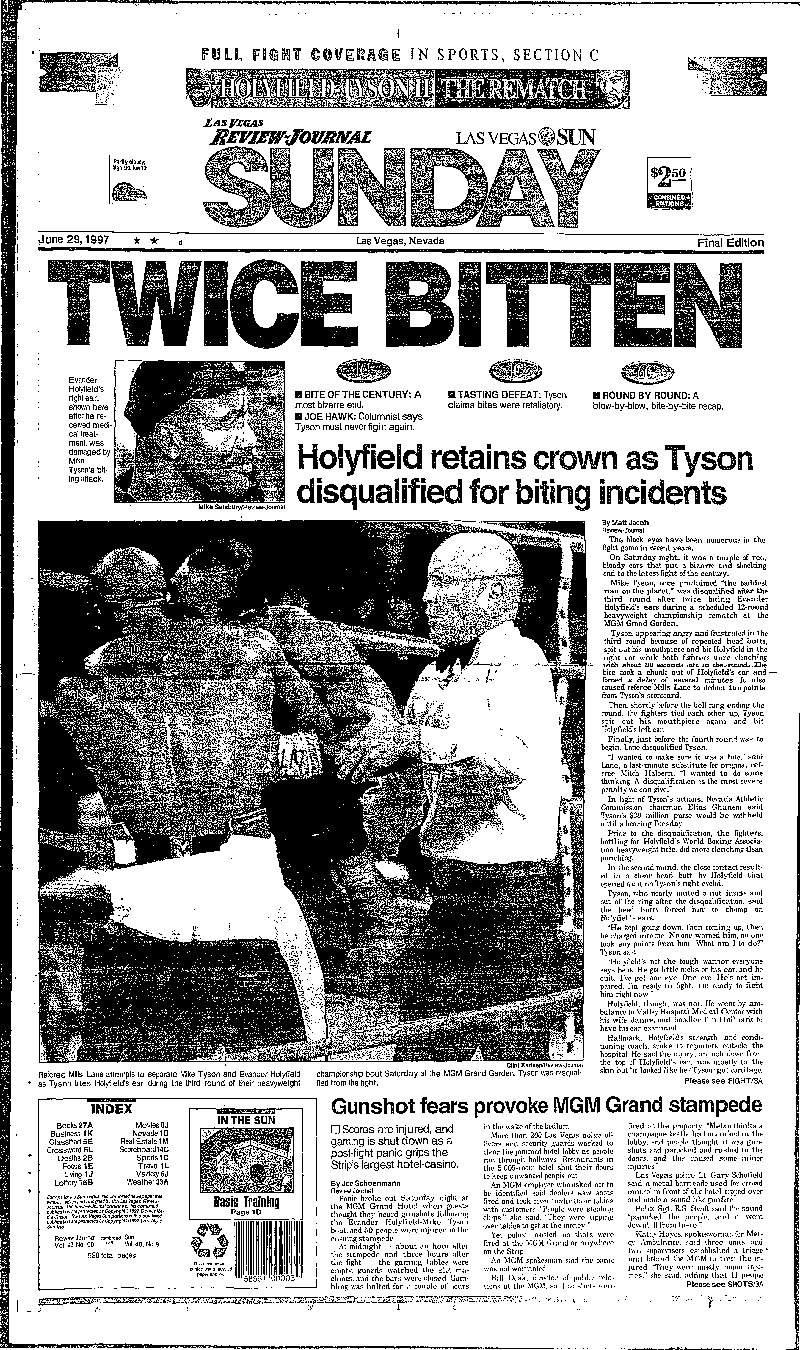

Dubbed “The Sound and the Fury,” Tyson-Holyfield II would spawn books, documentaries, myriad song references — from Beyonce to Run the Jewels — and forever intertwine the lives of two boxing Hall of Famers.

Who you rooted for on June 28, 1997, said something about you: Did you cheer for the quiet, pious man who didn’t even complain all that much when he was totally robbed of a gold medal at the 1984 Olympics? Or were you rooting for the grizzly-bear-menacing physical specimen who — despite his long-standing protestations of innocence — was once convicted of rape, that villain who scared you so thrillingly in the boxing ring instead of beneath your bed?

(More folks put money on the latter, who came in as a 2-to-1 favorite).

Even its brevity, even with a quarter century to digest the unprecedented mayhem of that night, Tyson-Holyfield II still stands as one of the wildest fights of all time.

“What happened here?” play-by-play announcer Steve Albert wondered on the Showtime pay-per-view broadcast, which set a record at the time with 1.99 million PPV buys, nearly $100 million in revenue on top of a $17.2 million gate.

Twenty-five years later, it’s a question worth repeating.

What happened here?

Long-awaited showdown

It was the kind of punch that takes a man’s legs from him, robs him of his spirit and his ability to stand upright in one brutal swing.

Mike Tyson landed the thing — a short, fired-from-a-cannon left hook — right on the nose of Evander Holyfield, whose nasal cavity must have felt like a catcher’s mitt upon absorbing a 110 mph fastball.

Perfect shot.

Delivered in the fifth round of Tyson-Holyfield I on November 9, 1996, it was the kind of lights-out punch that should have sent Holyfield flat on his back, consciousness evacuating his body as swiftly as the sweat from his pores.

Instead, Holyfield just took it.

And then fired back.

It was like witnessing a great white shark sink its teeth into the hull of an ocean liner — a normally devastating act rendered null. Few could believe what they were seeing — least of all Mike Tyson.

“This is going against just about everyone’s thoughts,” observed Showtime’s Albert on the broadcast.

Tyson and Holyfield are meeting in the ring for the first time as pros in a fight titled “Finally” for good reason: The two had been circling each other since their amateur years in the early ’80s, having once sparred briefly when they were both trying to make the ’84 Olympic team, the session quickly halted after less than one round when things started to get so heated that it was stopped by a coach who feared that someone might get hurt.

They were later on course to fight in the second half of 1990, but Tyson lost what was supposed to be a tuneup bout in February of that year to underdog James “Buster” Douglas in one of the greatest upsets in boxing history. The two were next scheduled to clash at long last on Nov. 18, 1991.

But Tyson injured himself in training, bumping things back once more, and then in the spring of 1992, was sentenced to six years in prison for sexually assaulting a beauty pageant contestant.

The fight was off. Again.

Upon being released from prison in 1995, Tyson made quick work of a quartet of overmatched opponents, none of the fights lasting more than three rounds.

Tyson looked like his young fierce self while Holyfield — who’d won and lost a heavyweight belt in the meantime — struggled to get a win in a subpar performance against faded contender Bobby Czyz in May 1996, his final scrap before the Tyson showdown.

Holyfield’s long-awaited fight with Tyson didn’t look like it was going to be much of a fight at all.

“The reason that Mike fought Evander is that Evander looked so bad the fight before,” recalls Marc Ratner, then the executive director of the Nevada State Athletic Commission, which sanctioned the bout. “It looked like Tyson would knock him out in two or three rounds.”

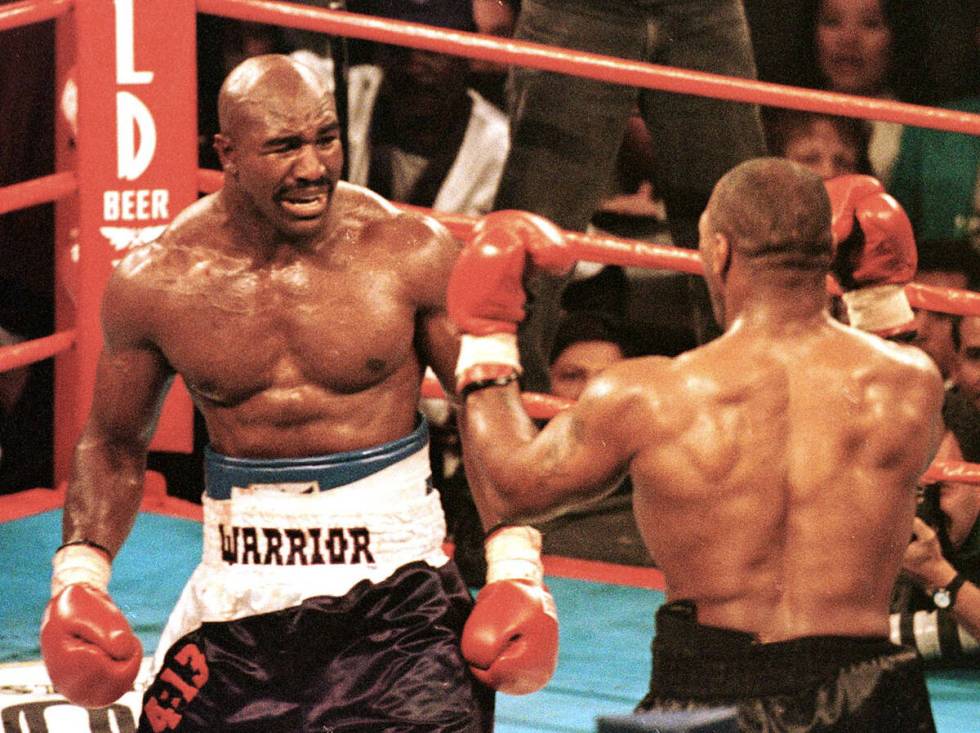

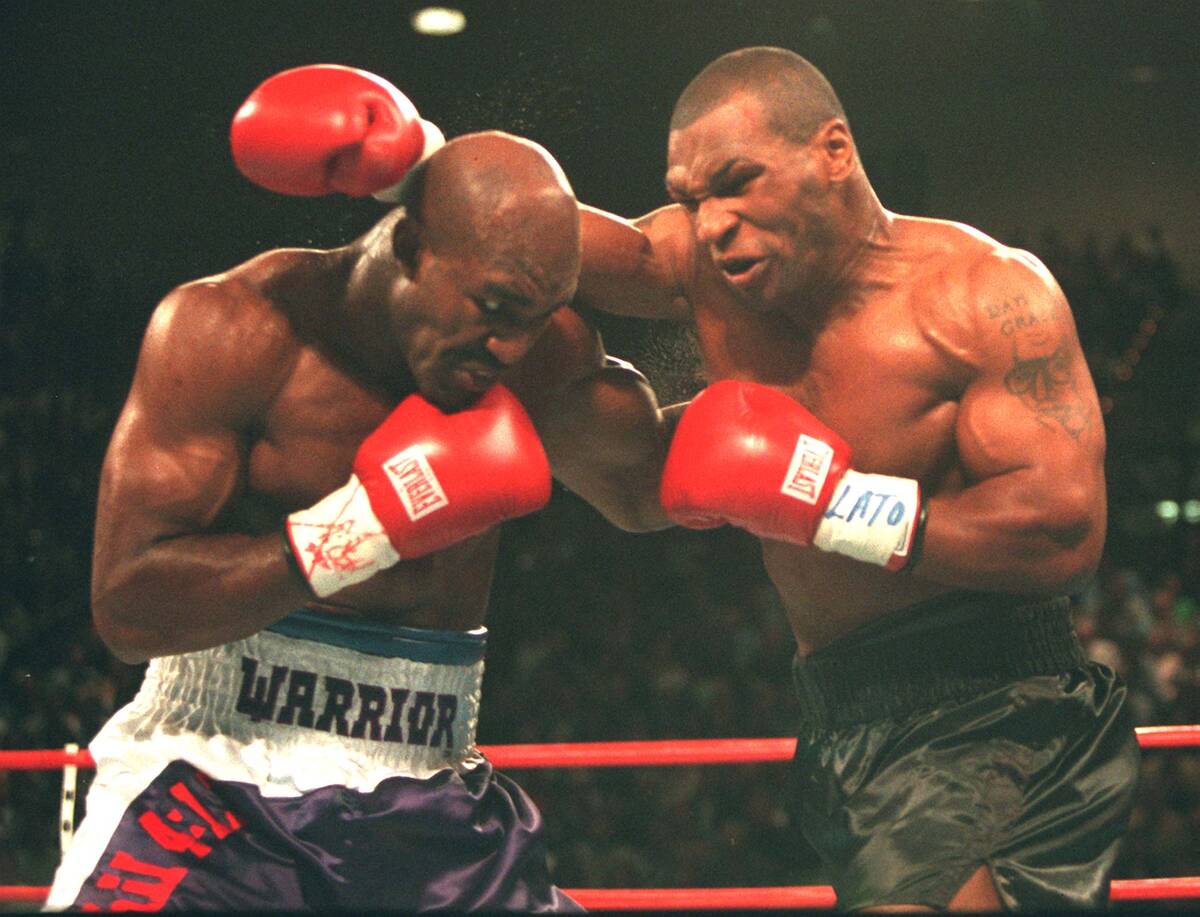

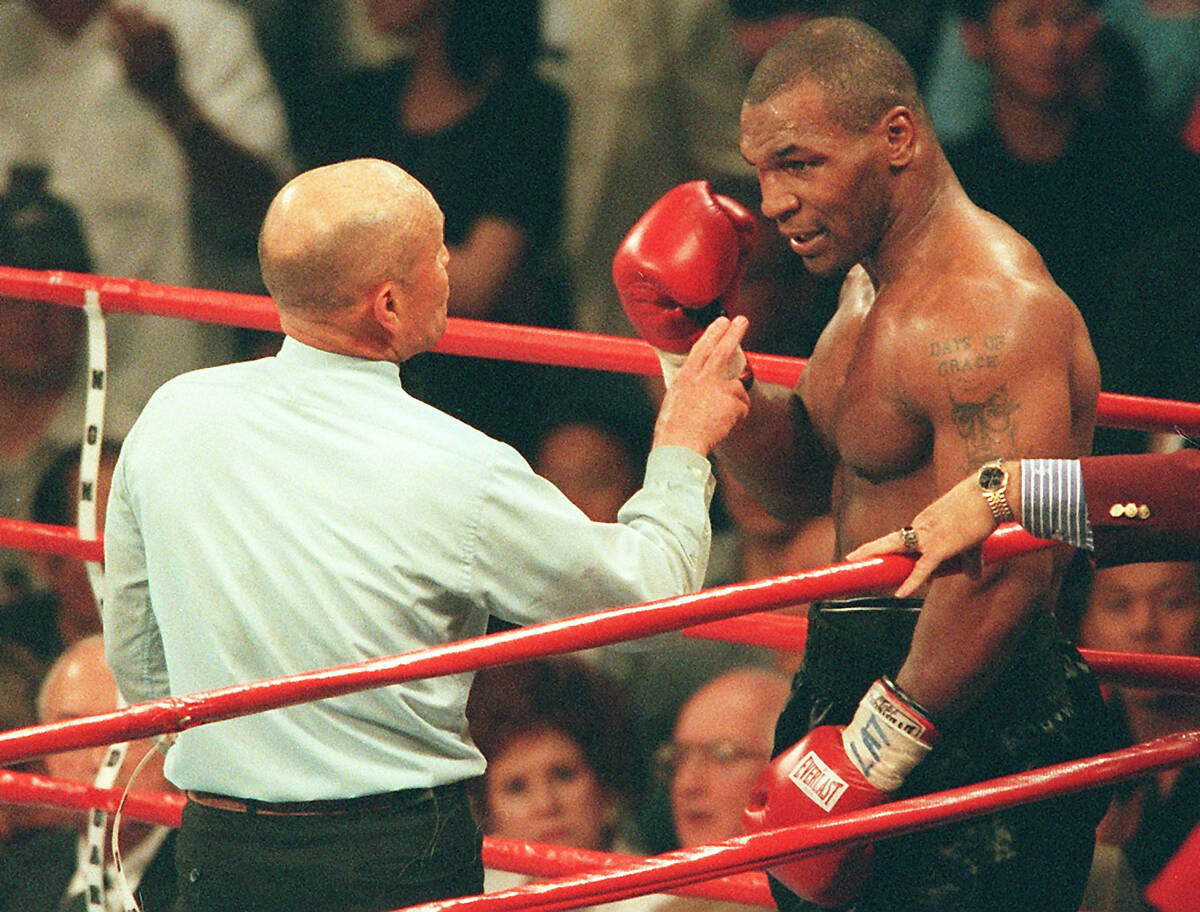

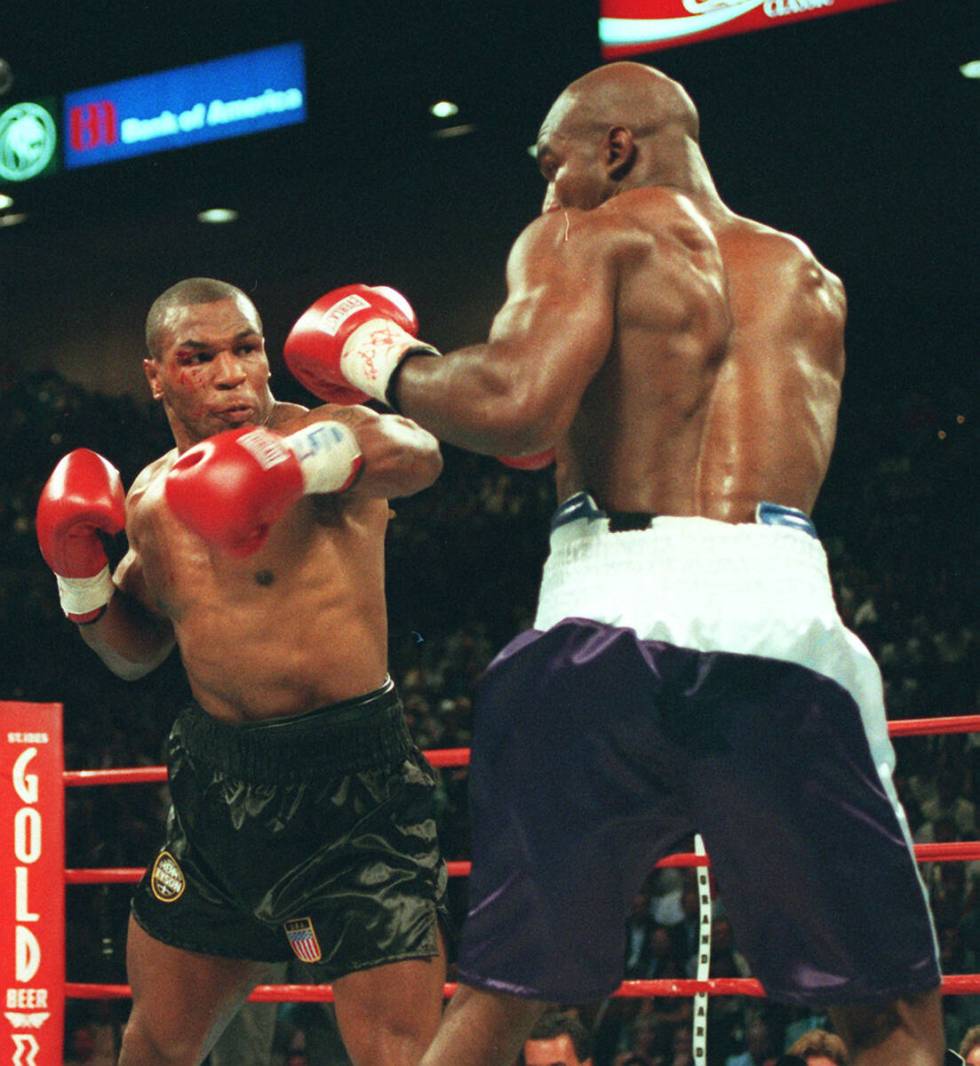

Mike Tyson biting into the ear of Evander Holyfield in the third round of their WBA heavyweight match in Las Vegas on June 28, 1997. Tyson, whose meteoric rise to the pinnacle of boxing and stunning fall from grace was legendary, later was selected for induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and Museum. (AP Photo/Jack Smith, File)

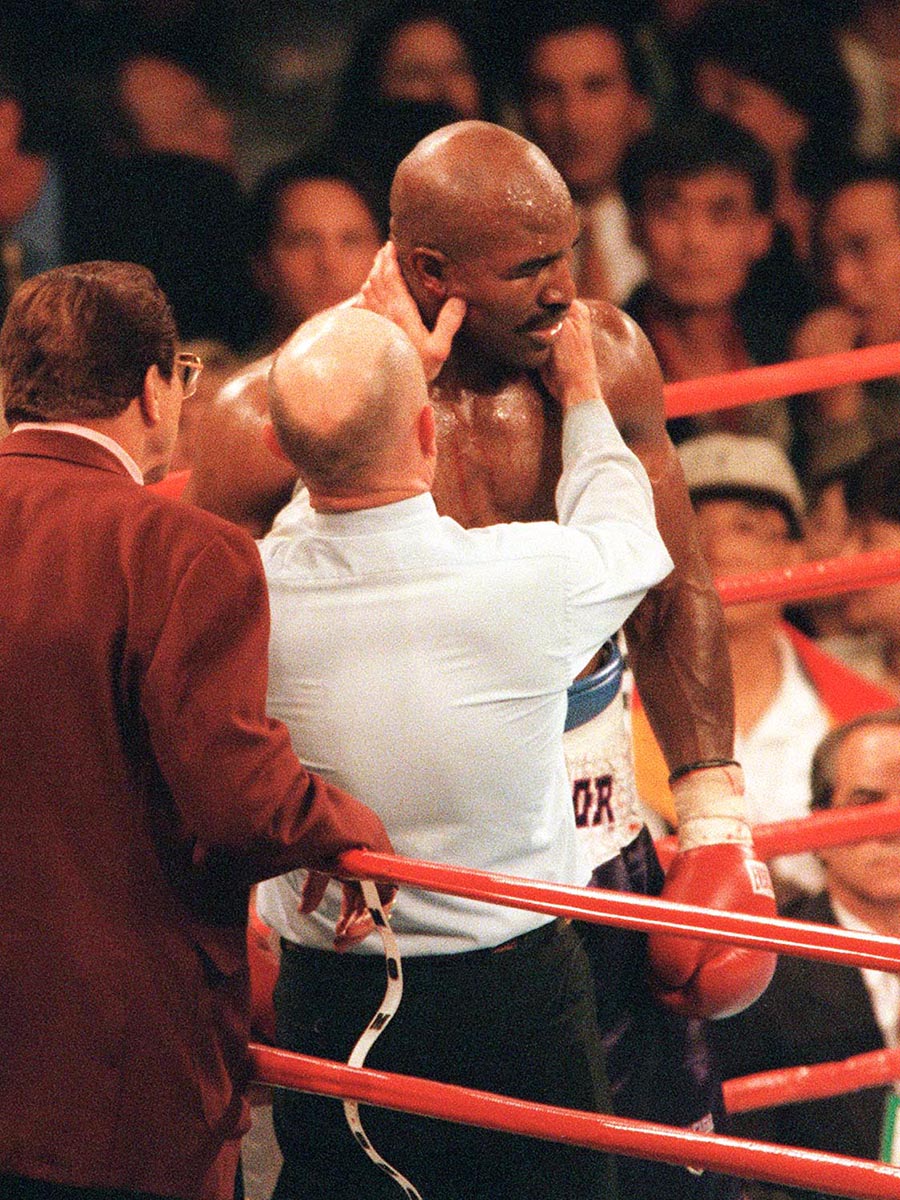

Mike Tyson biting into the ear of Evander Holyfield in the third round of their WBA heavyweight match in Las Vegas on June 28, 1997. Tyson, whose meteoric rise to the pinnacle of boxing and stunning fall from grace was legendary, later was selected for induction into the International Boxing Hall of Fame and Museum. (AP Photo/Jack Smith, File)  Referee Mills Lane examiners Evander Holyfield’s ear after Mike Tyson bit him during their match at the MGM Grand Garden Arena. Photo: Clint Karlson/Las Vegas Review-Journal.

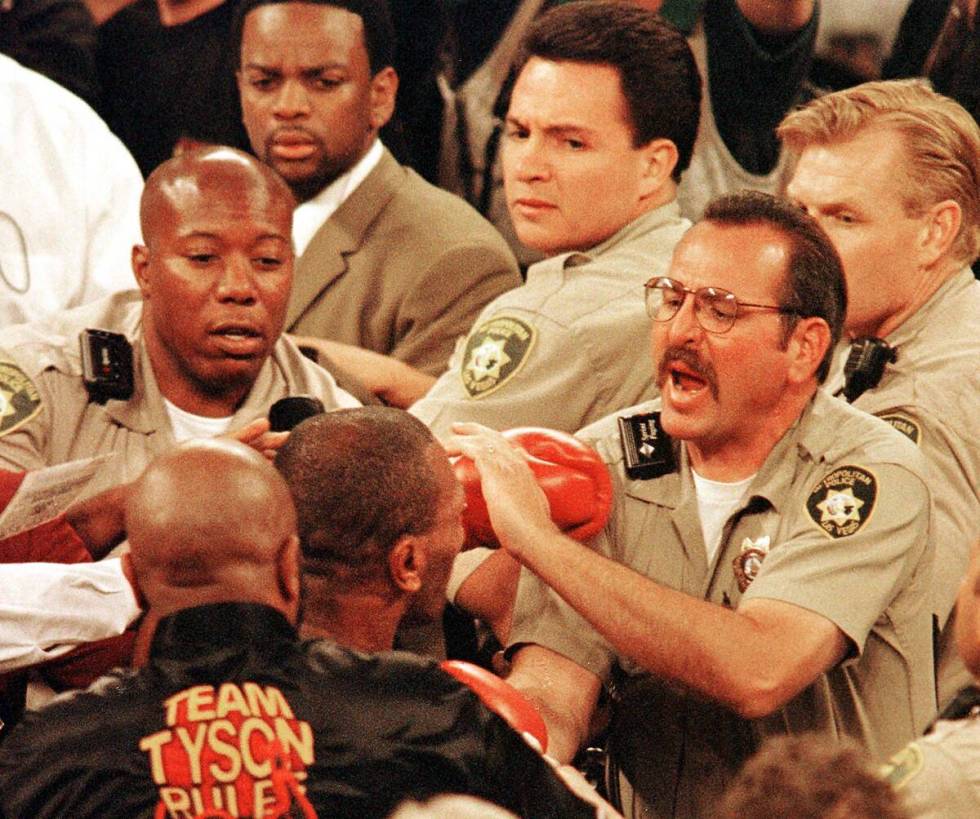

Referee Mills Lane examiners Evander Holyfield’s ear after Mike Tyson bit him during their match at the MGM Grand Garden Arena. Photo: Clint Karlson/Las Vegas Review-Journal.

Underdog bites. Hard.

Just about the only person who thought that Evander Holyfield could beat Mike Tyson was Evander Holyfield.

In a poll of 40 sportswriters before the fight, Ron Borges of the “Boston Globe” stood alone in predicting a Holyfield win.

When the bout was first announced, Tyson was a 25-1 favorite.

It all added to the boulder-sized chip on Holyfield’s shoulder. Despite having more losses than Tyson at the time, he’d also faced a higher caliber of opponents and earned more quality wins. For all his fearsome knockout power, Tyson’s biggest victories were against a past-his-prime Larry Holmes and a blown-up former light heavyweight champ in Michael Spinks.

“Holyfield beat everybody, all the great boxers of the day — he fought ’em all and beat ’em all,” says producer/fimmaker Steven Cantor, who directed the ESPN “30 for 30” documentary “Chasing Tyson.” “Tyson never had that fight where you’re just like, ‘Wow, he really hung in there and outboxed a great boxer.’ Never had that in his career.”

And yet, Tyson was unarguably the more popular fighter of the two, a man whose missteps in and out of the ring had cost Holyfield massive paydays when their previous fights were scuttled.

“Holyfield had this ghost of a person overshadowing everything in his life,” Cantor continues. “Until he was able to conquer that, he would never earn his own self-respect or the respect of the boxing population. He knew that he could beat Tyson. There was no doubt in his mind. He did not think that Tyson could hurt him.”

And he fought like it.

From the opening bell, Evander Holyfield entered the eye of the storm and became the storm, delivering lightning strikes to his opponent, pressing the action against a man few dared to press the action against. He forced Tyson to fight backward, using his quicker hand speed to pepper Tyson with blows and then clinch when he got in too close.

The times that Tyson did land a flurry of shots — like a battery of punches in the sixth round — Holyfield absorbed the punches and just kept coming forward.

Also in the sixth round — and again in the seventh — head clashes between the two fighters, which referee Mitch Halpern ruled accidental, bloodied Tyson’s brow, further frustrating him and throwing him off his game. (He’d later argue they were deliberate by Holyfield).

As the fight progressed, Tyson became less aggressive, more angry.

The bully was getting bullied.

“The Tyson mystique is not having any hold on Evander Holyfield,” Albert observed during the broadcast.

Finally, after having Tyson out on his feet at the end of the 10th round, Holyfield finished the job in the 11th, hammering Tyson into a stupor as Halpern called off the fight less than a minute in for a Holyfield TKO victory.

“I can’t believe what I’m seeing,” gasped Bobby Czyz, who was calling the action as part of the Showtime broadcast team. “It’s the most unbelievable thing I’ve ever been privileged to witness.”

Though Tyson lost convincingly, a rematch was set for the following summer and again Tyson opened as the betting favorite with 2-1 odds in his favor.

The Tyson mystique that Albert spoke of may not have had much of an effect on Holyfield, but it still enraptured legions of fans around the world who were sure “Iron Mike” would get his revenge somehow.

“Nobody ever knew what was going to happen with Mike,” says Brian Rogers, a ringside paramedic at numerous Tyson fights, including his rematch with Holyfield, who now serves as chief operating officer for the Henderson-based Community Ambulance. “Everybody knew what he was capable of. They’ve seen people go down within 30 seconds of the fight starting. At the time, he was known as one of the most dangerous boxers in the world or the most dangerous boxer in the world.

“But, he couldn’t beat Holyfield,” he adds. “And I think that’s why the second fight was so crazy.”

‘The fight of the decade’

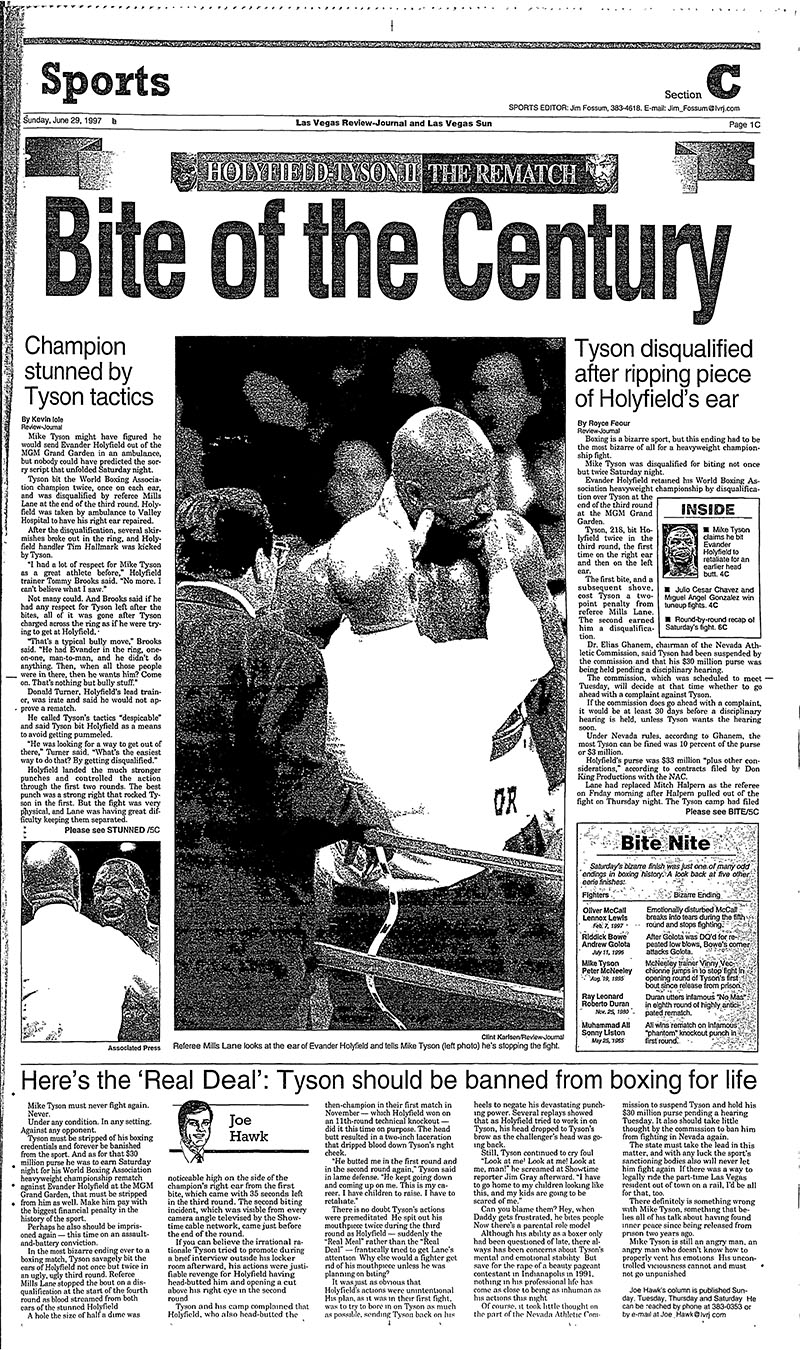

The picture’s worth 1,000 words, plenty of them expletives.

Marc Ratner’s looking at one of the many framed portraits that line the walls of his office/low-key sports museum nestled in the sprawling headquarters of the UFC, where he’s served as vice president of regulatory affairs since 2006.

In the shot, it’s fight night, and Ratner’s standing on the lip of the ring, wearing a what-the-hell-did-I-just see? look, this mix of consternation and confusion, as referee Mills Lane extends an arm toward an enraged Mike Tyson, as if to keep him at bay — as if that could keep him at bay.

Tyson has just removed a chunk of Holyfield’s ear with his teeth, and — as is often the case when someone takes a bite out of a co-worker at the office — everyone’s trying to figure out what to do next.

“Mills had called me up. He said something like, ‘He bit him. I’m going to disqualify him,’ ” Ratner recalls as he looks at the 25-year-old photograph capturing the aftermath of the Bite Felt ’Round the World. “I said, ‘Are you sure?’ ”

It had already been a wild week.

On Wednesday, Tyson’s camp protested Halpern being named the referee for the rematch on the grounds that he didn’t do enough to prevent/punish what they saw as purposeful head-butting by Holyfield — who at 6 feet 2½ inches stood 3 inches taller than Tyson — demanding a hearing by the Nevada State Athletic Commission.

“Holyfield had his number, but what people don’t know is that Holyfield had an educated head,” King contends of said fighter using his skull as a weapon. “And boy, did he know how to use it. (Tyson) got frustrated with that.”

Nevertheless, the NSAC kept Halpern on for the fight.

“I met with Mitch and said, ‘It’s up to you if you want to stay in here.’ It’s a $10,000 payday. It’s pretty hard to tell someone not to take $10,000,” Ratner recalls. “Now it’s Thursday night, he called me and said, ‘I’m not going to do it. I don’t want to be the center of it.’ ”

Enter Mills Lane at the last minute, the day before the biggest fight ever in Las Vegas up to that point.

Just how big was it?

According to Bill Doak, director of media relations at the MGM Grand at the time, there were 1,180 total media requests, 774 coming from international media members, with 17 international broadcasters coming to the fight.

There were so many journalists in attendance that they had to build a satellite tent outside the arena to accommodate everyone.

“That second fight was considered the fight of the decade at the time,” remembers Doak, who co-founded Vegas publicity firm Kirvin Doak Communications in 2002. “The energy and the intensity of the people on the property and the celebrity aspect, the media attention that it drew, was like nothing else I had ever done.”

“Every network was covering it, ” Cantor adds. “Everybody wanted to be at their training sessions; everybody wanted to go to all the press conferences — the press conferences were packed. It’ll never get to that level again. It was such a monumental event.”

There was so much on the line that Mills reconsidered disqualifying Tyson after that first bite, instead deducting two points from him and then allowing the bout to continue when the ringside doctor, Edwin “Flip” Homansky, said that Holyfield was able to keep fighting.

And then, seconds later, Tyson bit him again.

The fight was over.

The melee was on.

Something to chew on

OK, so why’d he do it?

Twice.

Tyson long has cited his frustration with Holyfield’s allegedly intentional head-butting as the reason he took matters into his own mouth.

“It was a terrible discrediting to boxing, he bit the guy’s ear,” King says, building his argument for Tyson, though the two are hardly on the friendliest of terms these days, the fighter having sued his former promoter for $100 million in 1998. “But he bit the guy’s ear because, what people don’t know, is that Holyfield had three arms — because he used his head as an arm. Every time they’d clinch, he’d bop him with the head.”

It happened again in the rematch: in Round 2, Tyson’s face was once more smeared with blood from a clash of craniums.

“Deja vu!” Alberts exclaimed on the broadcast.

Ratner didn’t think the butting was intentional, though he acknowledges how much it angered Tyson early in his second fight with Holyfield.

“I never believed that Evander butted him on purpose,” Ratner says, “but the way they fight, their heads clash and there’s a cut. You can see that already Tyson’s infuriated.”

Either way, Holyfield was having his way with Tyson once again.

“I remember the first round, I thought Holyfield was going to knock him out,” says Duane Ford, current president of the North American Boxing Federation, who was one of the judges at ringside for Tyson-Holyfield II. “I kept thinking to myself, ‘Don’t go,’ because I’m ready to score the whole fight. I wanted to do all the rounds.

“The second round was about the same,” he continues. “The third round, Tyson came out and he tried everything. If he missed him with his punch, he tried to connect with the elbow. He did everything he could.”

It wasn’t enough. Holyfield continued controlling the action, as in the first fight.

For Hallmark, Tyson’s inability to solve the prize-fighting puzzle that was Evander Holyfield is ultimately what led him to lash out in the manner that he did.

“I think the frustration is what triggered, ‘I don’t want to do this all night. This is no fun. This is not what I’m used to,’ ” he says.

At the start of the third round, Tyson initially left his corner without his mouthpiece.

You know what happens next.

“I believe that when Mike came up to the apron in that round, he’d already decided he was going to do something to stop it,” Hallmark contends. “Now, whether or not he decided, ‘If I bite him, I know they’ll stop it,’ I don’t know if all that was premeditated.”

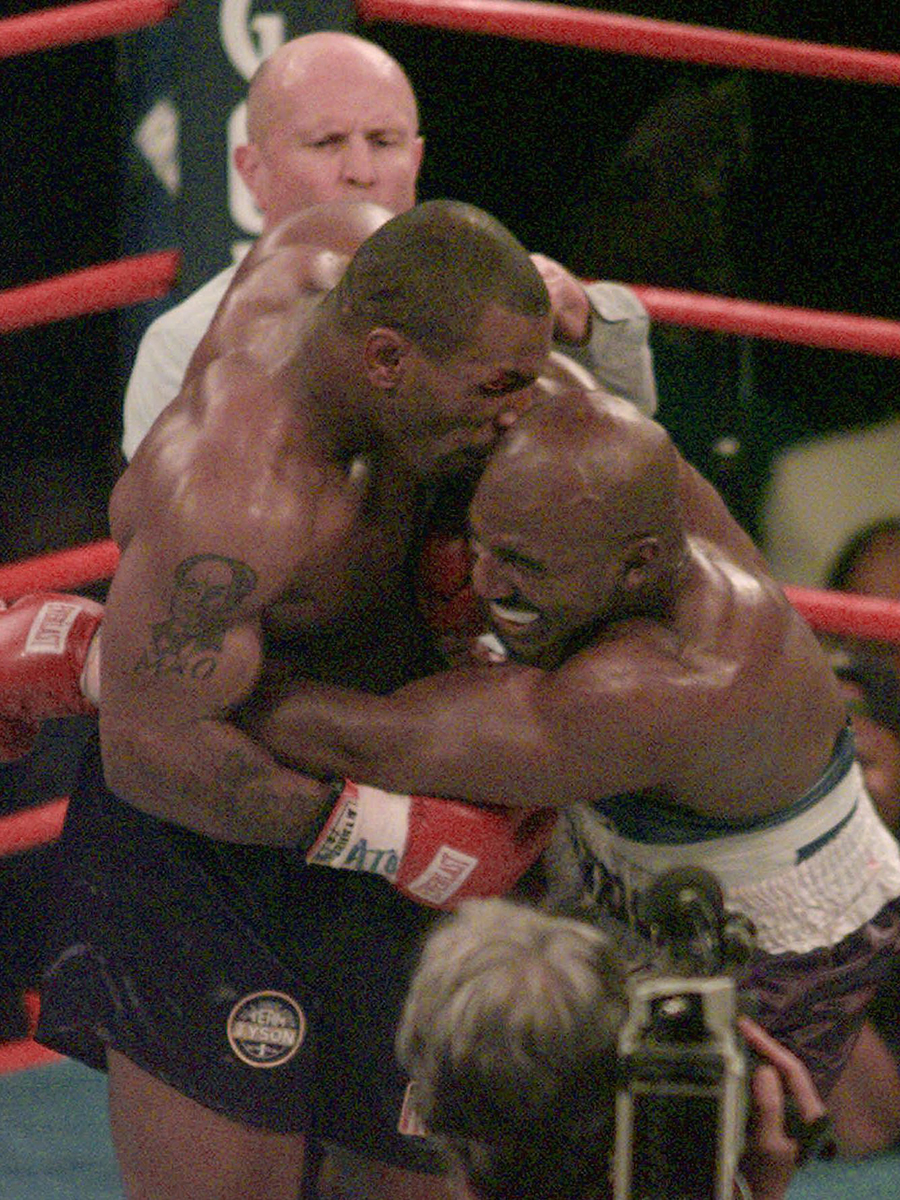

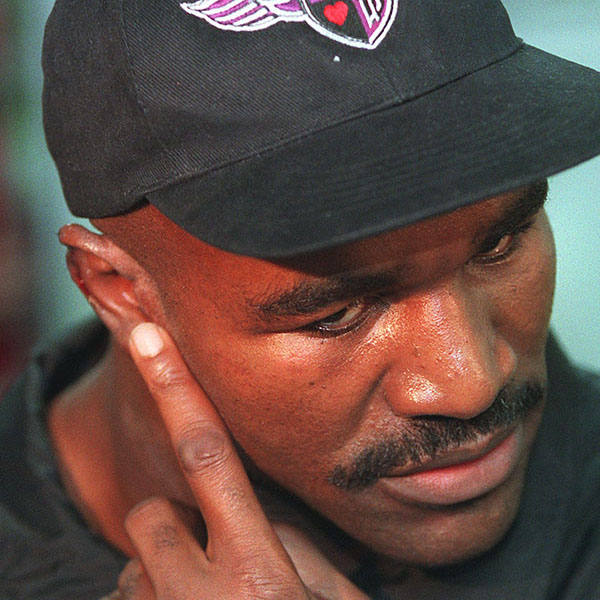

Whatever Tyson’s true motives were, when Lane DQ’d him after the second bite, the whole room erupted like a suddenly awakened fault line.

Police officers swarmed into the ring, which looked like a mosh pit in the middle of a rugby scrum, as Tyson seemed ready to swing on anybody and everybody, all at once.

Hallmark was smack in the middle of the mayhem.

“All I could think about was, ‘You know what? I’m not going to get hit from behind. I’m not going to let somebody cold-cock me,’” he recalls. “I kind of just got my feet real wide so I could see everybody in the ring.

“It looked like Mike was coming towards me,” he continues. “I think Mike was in such an emotional, rage state then, I don’t know if he had singled me out or what, but he was wanting to get ahold of somebody. He was angry — to say the least.”

‘It was chaos’

As bedlam seemingly swallowed the MGM Grand Garden Arena whole, security engulfed both camps, attempting to herd everyone to safety as some fans hurled beers at Tyson, who looked as if the heat of the moment was boiling the blood in his veins.

“The tension was so thick, you could cut it with a knife,” Hallmark says. “You just didn’t know who might do what.

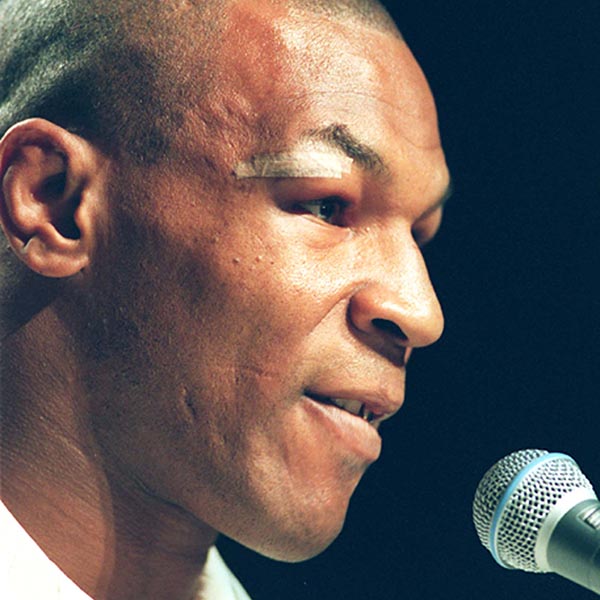

“They hustled us back to the locker room,” he continues. “Evander went straight over to the mirror in the bathroom. He wanted to see his ear. That’s when he really got upset. He saw that he had actually bit a hunk out of his ear.”

Per custom, ringside paramedic Rogers visited each locker room following the fight, hitting Holyfield’s first.

“I go in there, and Evander’s about to have a prayer … for Mike,” he remembers. “I’m like, ‘All right, he’s OK for now, let me go see Mike.’

“Well, I heard the commotion before I walked in,” he continues. “He was just in a rage — never seen anything like this before, and I’ve done many Mike Tyson fights. He was punching the walls. It was just crazy. I was like, ‘I don’t need to be in here right now. This isn’t my thing.’ ”

So, he headed back to Holyfield’s locker room, where Homansky gave him a red biohazard bag containing the remains of Holyfield’s ear, as well as some ice to keep it cold.

“He tells me, ‘You personally hand this to the hospital staff,’ ” Rogers recalls. “I said, ‘Got it.’ ”

Vegas-based plastic surgeon Dr. Julio Garcia was watching the fight at a friend’s house when Holyfield got maimed.

“I said to my buddies, ‘Some dummy’s going to have to go and take care of this problem,’ ” recalls Garcia, who has a long history of fixing up boxers after fights. “Lo and behold, I get a phone call, like, about a minute later from people at Valley Hospital. They said, ‘You’ve got to get over here right away because Evander Holyfield’s gotta get his ear fixed.’ It was crazy.”

He didn’t even have time to change clothes.

When Rogers got to the hospital, he took Holyfield directly to the operating room.

“I went with him as far as I could without being in a sterile area,” he says. “There was a nurse who takes all the information, takes my report, and then the bag with the ear in it.”

Figuring he’d done all he could do, Rogers who hopped in his ambulance thinking his night was over.

And then he got the call: There were reports of shootings at the MGM Grand.

“I’m like, ‘Oh, good God,’ ” he says. “So, I drove Code 3 to the MGM. We set up a command post at the main valet. I had never in all my years being in Las Vegas seen a casino closed.”

By the time Rogers got there, the property had been evacuated and was temporarily shuttered in the wake of a panicked exodus of fans after the fight’s dissatisfying conclusion, gaming tables upended, poker chips flying every which way.

“It was chaos,” Doak recalls. “People started running. People were angry and upset at what had happened. And there were different camps. There were Holyfield fans and there were Tyson fans, so things got heated. People started making for the exits and then started running for the exits.”

Reports of gunfire only heightened the frenzy, though no evidence was ever found of any arms being discharged.

Doak believes that what people actually heard was the loud, sharp crack of brass stanchions hitting the marble floor of the hotel lobby.

“People were running through the lobby,” he explains. “As they’re running through, those ropes and stanchions start coming down, those barricades start hitting the floor, and so when those brass stanchions hit, it was like a pop sound and it scared people.”

Mystery of AWOL ear

Of course a story this crazy isn’t just going to end without one more plot twist even crazier still.

Putting that whole “sometimes truth is stranger fiction” thing to the test, Rogers received yet another call as he was headed back to the MGM, this time informing him that the ear that he dropped off was … well, where was it, again?

“They say, ‘Brian, where’s the ear?’ ” he recollects. “I said, ‘I left it there.’ They said, ‘No, we don’t have the ear.’ ”

Garcia remembers seeing the bag upon arriving at the scene.

“When I get there, there’s a bag on the counter and the nurses told me — and some of the paramedics were there as well — ‘Hey, we’ve got the stuff in the bag, let’s just get this whole thing going,’ ” he says. “When I came out of the locker room, unfortunately the bag was missing.”

In one of the greatest mysteries to ever involve a chewed-off piece of flesh from a multimillion-dollar prizefight, the missing ear chunk was never found.

“We had a very small number of people there, we don’t know who took it,” Garcia says, “but we were kind of strapped, so I went ahead and told Holyfield, ‘Hey, listen, I’m going to take care of this. We’re going to do something a little bit different, bear with me.’ I went and did the surgery on him. I had to do a flap to close the right side of his ear a little bit to protect it.”

Hours later, between 1 and 2 a.m. by his estimation, Garcia got word that a worker at the arena had found a piece of cartilage from Holyfield’s ear in the boxing ring, this in addition to the part of the ear that had been discovered earlier.

“They called me, they said, ‘Hey, what can you do with this?’ ” Garcia says. “It was mangled; it had been dirty for a long time. I said, ‘We can’t put this on his ear, so we’re just going to have to throw it away.’ ”

Maybe the wildest thing about this whole AWOL ear caper?

None of it seemed to bother Holyfield all that much.

“He comes out of the room where he was finished dressing — he had the dressings on the ear that I had put on to contain it and not have it infected — he starts bouncing around, boxing in the air, like boxers do,” Garcia says of the fighter’s playful post-surgery demeanor. “And he looks at me and he goes, ‘Hey doc, I look like a Doberman pinscher.’ ”

Fight’s fallout

After Tyson’s disqualification, his purse was held by the Nevada State Athletic Commission until a meeting at city hall a few days later.

“It looked like an antennae farm with all the big trucks around, the streets blocked, I never saw anything like that,” Ratner recalls of the media coverage of the hearing.

The commission revoked Tyson’s license, which meant that he couldn’t fight anywhere in the world until reapplying for it in a year, and fined him $3 million, 10 percent of his announced payday of $30 million.

“Which is an astounding fee, even to this day,” Ratner says.

It’d be hard to argue that the ear-chomping debacle had any lasting negative impact on Tyson’s popularity: He’d get another big bite of the apple — and his opponent — in 2002, when he took on heavyweight champ Lennox Lewis in a blockbuster showdown that did even bigger business than his fights with Holyfield. (The clash was originally supposed to be held in Las Vegas, but after a scrum at a news conference in New York City, where Tyson bit Lewis on the leg, Nevada refused to sanction the bout).

Tyson would retire in 2008; Holyfield would follow three years later.

They’ve long since made amends with one another: In 2009, the two met on “Oprah” where Tyson apologized in person to Holyfield.

Four years later, they’d appear on “Larry King Live” together, where Tyson detailed why he did what he did on that fateful night.

“Because I had to,” he explained. Sort of. “I wanted to. I bit his ear. I didn’t mean to bite his ear. I bit his ear.”

Holyfield later acknowledged in the interview that he had every intention of biting Tyson back.

Ultimately, it was Hallmark who calmed him down.

Keep your eyes on your job, man.

The two were in talks to face each other for a third time in an exhibition fight last May in Miami before negotiations fell through. (Mike Tyson declined to take part in this story; an Evander Holyfield representative did not respond to an interview request).

The saga of Evander Holyfield and Mike Tyson, then, will forever have the most abrupt of endings, it seems.

There can be no question, though, that their two fights changed the way both will go down in history.

Holyfield braved the boogeyman, he faced the collective fear at the root of our fascination with Tyson.

Tyson scared us — and we liked it.

But he didn’t scare Holyfield.

Turns out we liked that even more.

We all know the old adage about how to deal with a bully: All you have to do is summon the courage to stand up to him, right?

A bit easier said than done.

But Evander Holyfield actually did it — and won — a vicarious victory for anyone who’s ever struggled to do the same.

Now, Tyson was hardly transformed into a warm, cuddly, sniffer of flowers upon his losses to Holyfield — just pester him on an airplane these days and see what happens; pro tip: Wear a helmet! — but in a way, Holyfield humanized him, revealed the person behind the persona of menace, and enabled Tyson to acknowledge feelings that he’d never shared before, a vulnerability that made him far more relatable than he’d ever been up to that point.

And while the madness of Holyfield-Tyson II might not have had an enduring impact on boxing itself — “I don’t think it tarnished the sport in the least,” Ford contends. “In fact, I think it probably created some excitement for the sport.” — there is at least one lingering effect of the fight.

In Garcia’s office hangs a photo of the infamous bite as it happened.

When Tyson comes in for a visit, he takes the picture down.

He doesn’t want to upset the man.

Mike Tyson is only human, after all.

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @jbracelin76 on Instagram