How David Benavidez morphed into ‘The Mexican Monster’

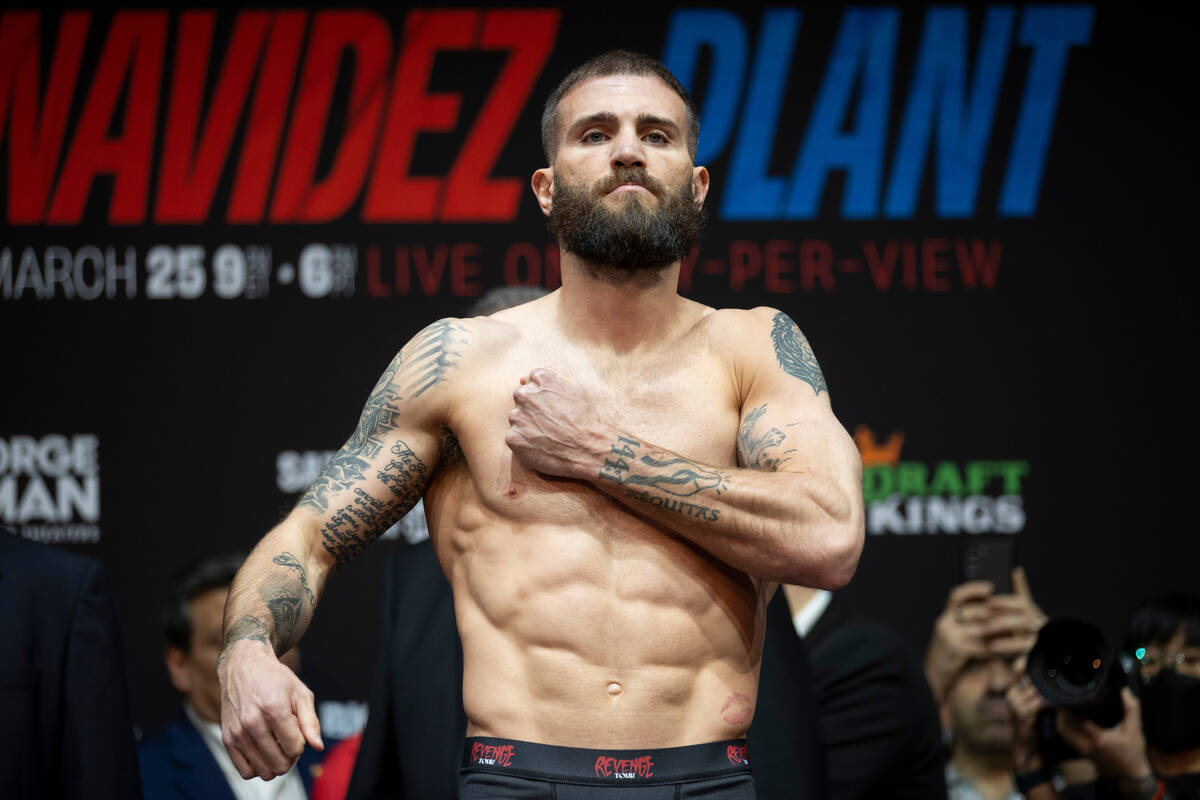

When David Benavidez looks into a mirror, he sees one of best boxing’s super middleweights, equipped with the charisma and power to become one of the sport’s next stars — and the lean, chiseled physique befitting a fighter of his caliber.

He no longer sees the bloated, blubbery 260-pounder who lacked the discipline to make his dream come true.

He sees the Mexican Monster.

“I had to conquer maturity. I had to conquer weight,” says Benavidez, now 26 and free from the mischievousness of his youth. “I told myself I was going to be one of the best world champions and one of the best of my generation. … I’m manifesting everything I said I was going to do.”

Benavidez (26-0, 23 knockouts) can cinch his superstardom Saturday at the MGM Grand Garden by beating Caleb Plant, an equally driven former champion who represents one of the most significant challenges of his career. The only challenges more consequential than the one posed by Plant (22-1, 13 KOs) were the ones Benavidez faced internally, conquered only by the focus he now harnesses.

Twice the WBC’s 168-pound champion — and the youngest in the division’s history — Benavidez was stripped of his title once for using cocaine and a second time for missing weight.

“Thank God we caught that early in his career,” his father and trainer, Jose Benavidez Sr., said. “You can lose anything you’ve worked for so hard in a matter of seconds.”

Making the Monster

The Mexican Monster moniker was bestowed upon Benavidez by heavyweight legend Mike Tyson, who attended fight week festivities this week and mingled for a moment with his proverbial protege.

Iron Mike x The Mexican Monster.#BenavidezPlant #Showtime #PPV pic.twitter.com/5T1kT5nOXg

— SHOWTIME Boxing (@ShowtimeBoxing) March 23, 2023

Like Tyson, Benavidez pressures opponents relentlessly — packing pop in the punches he throws from seemingly every angle with hand speed more suited for a welterweight.

Like Tyson, Benavidez indulged too much in temptation — moving from Las Vegas to Seattle to mitigate the desire.

He hails from Phoenix and trained under the tutelage of his father, a Mexican immigrant who endured a troubled childhood and sought to shield his sons from the horrors of humanity.

“I had to go through a lot in life. Child abuse. Molestation. Anything you can think of,” said the elder Benavidez, whose namesake, Jose Jr., was once the WBA’s interim 140-pound titlist.

“When I was growing up, I thought, ‘Whenever I had family, I’m going to be there to protect them. I’m not going to let nobody touch them. I’m going to make monsters. I’m going to make animals so they can defend themselves.’”

So he began training his two sons in their garage and backyard, beginning when David was 2. David followed and admired his older brother, an accomplished amateur who moved in 2009 with their father to Los Angeles, leaving little brother behind to live with his mother.

Without his father keeping tabs on his training, David Benavidez veered toward fast food and away from boxing. He would skip school to sleep and gain 100 pounds in one year as the calories compounded.

Insecurities emerged as his confidence crumbled.

“People were making fun of me behind my back,” he said. “I didn’t want to be that type of person anymore. I wanted to prove everyone wrong.”

That triggered a move to Los Angeles, where Benavidez reunited with his father and resumed his intensive training. He sparred with seasoned professionals and shed the weight within a year, eventually earning an invitation to Gennady Golovkins’s training camp in Big Bear, California — and the chance to spar with the former middleweight king.

The sparring sessions, Benavidez said, helped mold the rugged style he now employs.

“He was trying to kill me, and I was trying to kill him,” said Benavidez, who debuted as a professional in 2013 at 16.

Maturing the Monster

By 2017, Benavidez was a Las Vegas resident and world champion, defeating Ronald Gavril at Hard Rock Hotel to become the WBC’s titlist at 20. But the spoils of success overwhelmed the former champion and led to a positive drug test in 2018.

Too much too soon. To Seattle he would go.

He won the belt back a year later from Anthony Dirrell … only to lose it in 2020 by missing the super middleweight limit before his first defense.

“Now I know my body more than anything,” said Benavidez, having since added a nutritionist to his team. “I’ve learned a lot. I’ve had a lot of experiences in my life that have brought me where I’m at today.”

Indeed the missteps have motivated Benavidez, a man matured by his relationship with his girlfriend, Karina Silva, and their 2-year-old son, Anthony, an early enrollee in the school of the sweet science. Like the weight he once carried, Benavidez’s insecurities have all but evaporated — summoned subconsciously for fuel when he steps inside the squared circle.

Mature and measured as he may be, he’s as savage in the boxing ring as his record would suggest, bringing a string of six straight knockouts with him to Las Vegas.

“He comes to hurt people,” his longtime promoter, Sampson Lewkowicz, said.

And that, most likely, won’t ever change.

The Mexican Monster nickname can become an identity Saturday the way Benavidez can become the superstar he promised himself he would be.

“This fight with Caleb Plant, he woke up that monster in him,” Jose Benavidez Sr. said. “He’s crazy, man. He’s crazy. (But) in life, you’ve got to be crazy in in order to good things. If you’re normal, you’re not going to get nowhere. I see him on a different planet.”

Contact Sam Gordon at sgordon@reviewjournal.com. Follow @BySamGordon on Twitter.

Up next

Who: David Benavidez (26-0, 23 KOs) vs. Caleb Plant (22-1, 13 KOs)

When: 6 p.m. Saturday

Where: MGM Grand Garden

TV: Showtime pay-per-view ($74.95)

Tickets: Beginning at $104 on axs.com

Odds: Benavidez -380, Plant +320

Tale of the Tape

David Benavidez

Age: 26

Hometown: Phoenix

Record: 26-0, 23 knockouts

Height: 6-2

Weight: 166¾

Reach: 74½ inches

Caleb Plant

Age: 30

Hometown: Nashville, Tennessee

Record: 22-1, 13 knockouts

Height: 6-1

Weight: 167¼

Reach: 74 inches