Undrafted Las Vegan Orlando Robinson charts course to NBA

The optimism that filled Orlando Robinson’s 10th-floor suite inside ARIA Resort and Casino dissolved into an uneasy anxiety.

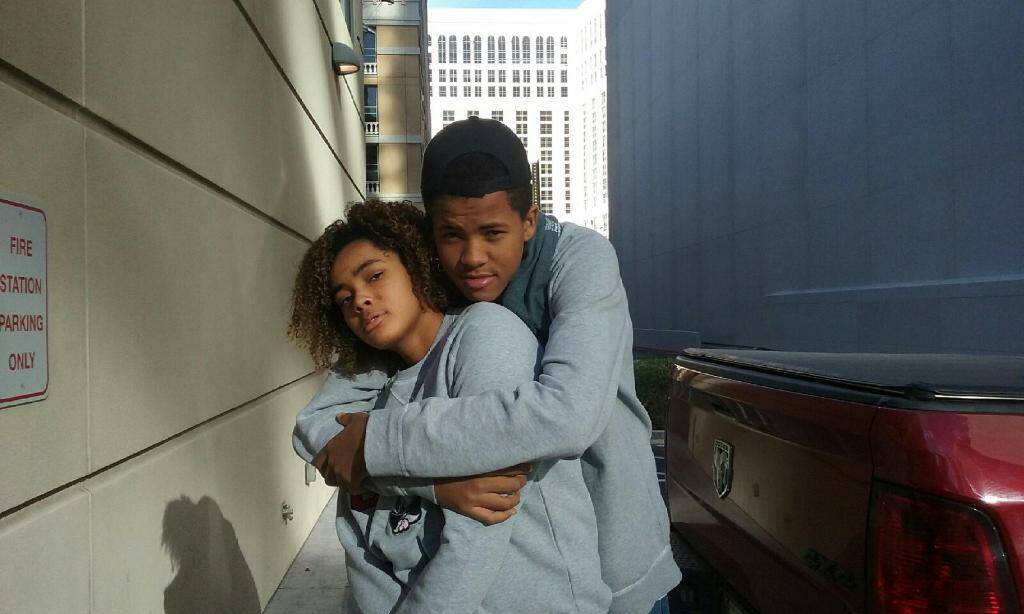

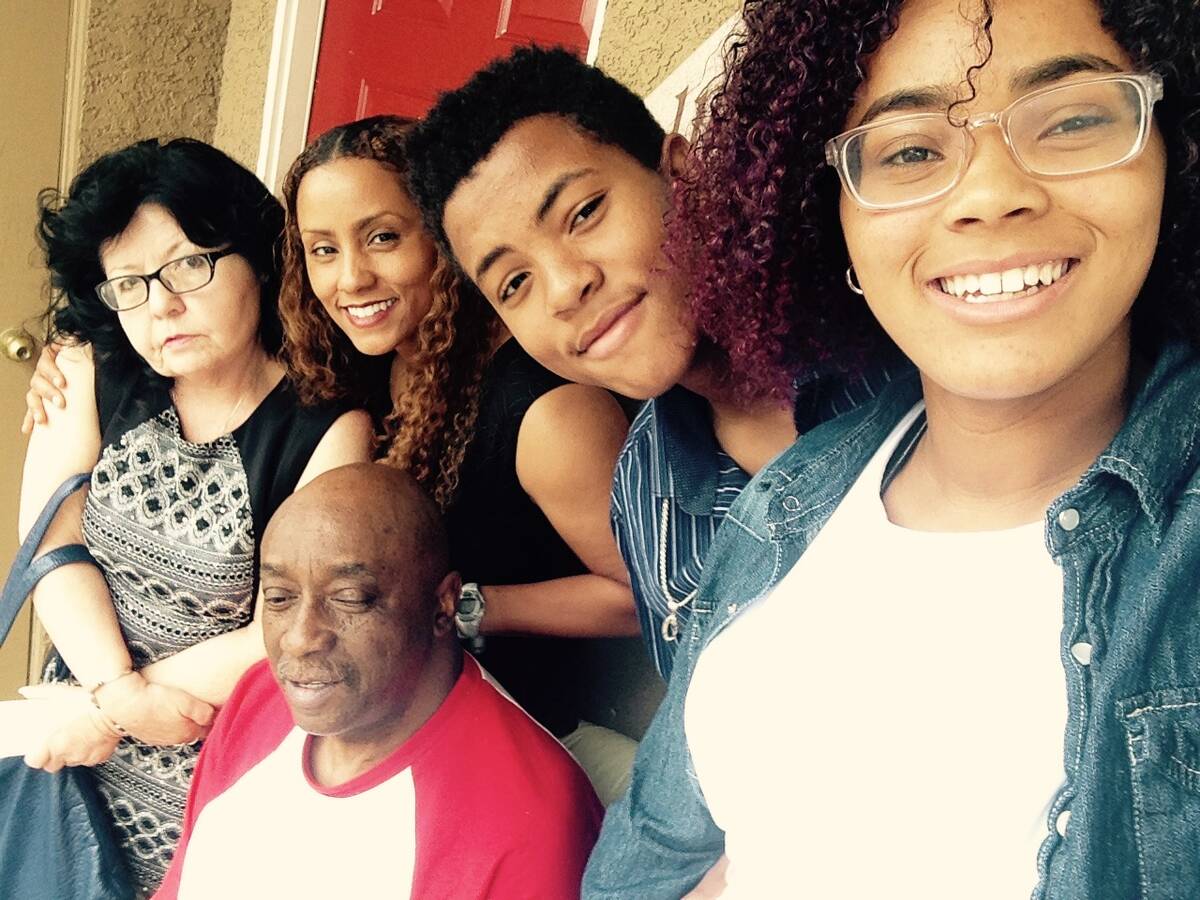

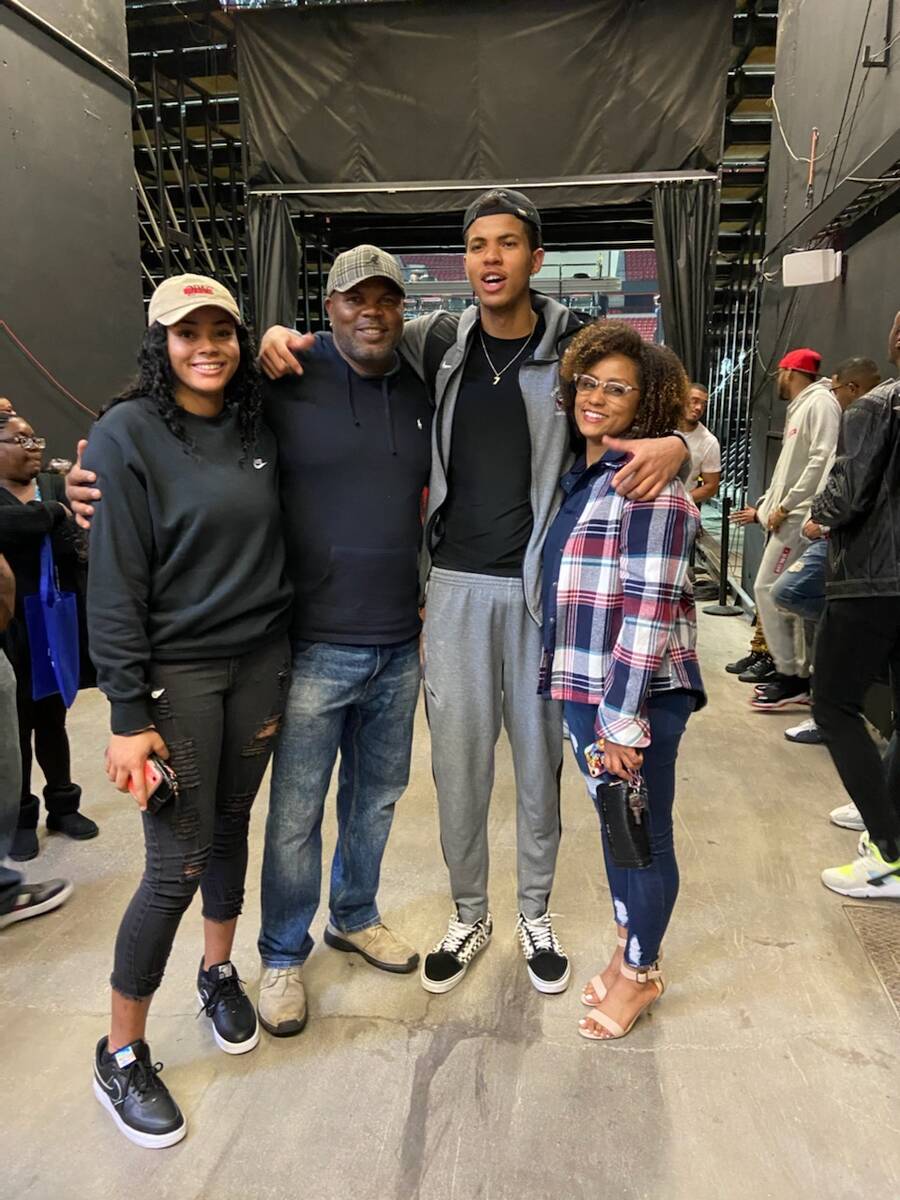

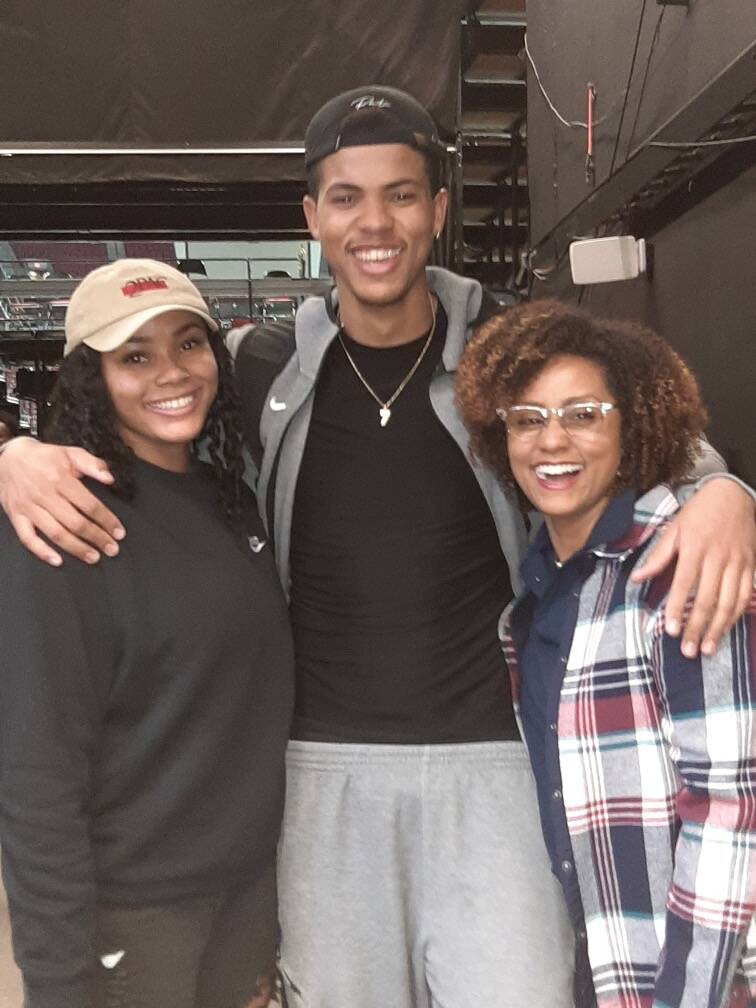

Then disappointment for the 25 or so family members and friends who joined the proud Las Vegan on what should have been the best night of his life.

Four hours passed and Robinson was not selected in the 2022 NBA draft.

Undrafted and undeterred, he excused himself to the suite’s bedroom to convene with agent Darren Matsubara, who used the space as a makeshift office — and brokered a contract for Robinson with the Miami Heat upon the draft’s conclusion.

“This ain’t nothing new,” Robinson told Matsubara. “I’m used to being overlooked.”

And underrated. And unsatisfied.

“Let’s get to work,” he said. “South Beach, baby. This is what we do.”

While Matsubara explained the nuances of the deal to Robinson’s family, the affable 7-footer found respite and solitude inside that bedroom and abandoned the fleeting discouragement five minutes later as he rejoined his draft party. His greatest gift isn’t his 7-foot-4-inch wing span or his passing proficiency from the high or low posts.

His sense of introspection is far more valuable, his maturity unusual for 22.

He bears no resentment toward the middle schoolers who once ridiculed him. No malice toward the coaches who benched him, the universities that didn’t recruit him or the NBA teams that didn’t draft him.

Just gratitude for the Heat, for whom he posted 12 points and eight rebounds during an 88-78 victory Saturday over the Boston Celtics in his Las Vegas Summer League debut at Cox Pavilion.

”He believes in himself. So he’s going to make you believe, too,” said Robinson’s former Bible study instructor, Las Vegas Knicks program director Lamar Bigby, for whom Robinson played club basketball.

“That’s just the kind of dude he is.”

A love for the game

His height would suggest that he’s born to play basketball, but Robinson, or “O” to friends and family, used to dislike the assumptions that accompany that size and stature. Duh, he’s tall. Yes, he loves basketball. He loves it far more than football, soccer, baseball, volleyball, karate, dance, choir and all the other extracurricular activities Orlando Sr. and Christa Fells insisted he and sister Aadiah try as kids in the northwest part of town.

But they too served their purpose, helping cultivate in Robinson a natural curiosity and confidence while squelching any fear of failure.

“They deserved to try many things and not to be boxed in by what people would assume,” said Fells, a teacher turned firefighter, of her two children.

So Robinson would foster a love of anime and action movies and the Marvel Universe, much to her delight. And basketball, much to that of his father, a former Division-II power forward turned union pipefitter with a raspy, bellowing voice and penchant for player development.

Robinson watched his father play in recreational leagues around town, drawing inspiration from the fun he seemed to have competing during games. The daily workouts weren’t as fun, though, designed instead to steel junior’s 11-year-old mettle through ball-handling and shooting drills, defensive slides and down-and-backs.

The elder Robinson was strict and demanding while he coached his son. Those sessions usually took place at the Silver Mesa Recreation Center or the Bill and Lillie Heinrich YMCA.

“If you can deal with my voice and how I’m talking to you, then no other man is going to be able to intimidate you,” the elder Robinson told his namesake. “I want you to understand if his voice is deep, if he’s intimidating, I don’t want you to budge.”

And so he didn’t. He wouldn’t. No matter how many times he was neglected near the basket as a post player in a guard’s game — or mocked by his peers for his perceived lack of coordination. He’d respond with a smile, staying steadfast in his development and secure in his character as he adjusted to his ever-changing body.

By his freshman year, he stood 6-7, possessing raw, uncanny skills befit more for a guard. They grabbed Bigby’s attention during a junior varsity game that year in Centennial’s secondary gymnasium, sparking excitement about the player he believed Robinson could become.

Unranked, unbothered

At Centennial, Robinson was an afterthought, buried on the bench behind five-star prospect Troy Brown Jr. and a strong supporting cast. He played sparingly at the varsity level, even as a skillful 6-9 junior. But after a successful recruitment by the Knicks, he was a focal point, empowered to anchor their offense from the high post and develop into a Division I prospect.

He lacked refinement at first, but he’d harness his skills under Bigby’s staff of coaches, rejecting rides to practice from his coaches so he could take the city bus to their headquarters at Tarkanian Basketball and bask in his burgeoning independence.

“My development is in my hands,” Robinson said. “Nobody is going to believe in me. Nobody is going to put in more work than I am to my own game.”

With that in mind, Robinson opted to leave Centennial and Las Vegas before his senior season of 2017-18. He probably could have played a starring role. But he hadn’t yet done that and sought additional development as he pursued a Division I scholarship — electing to reclassify and transfer to Middlebrooks Academy in Southern California instead.

The college preparatory program usually requires a two-year commitment, per founder and coach William Middlebrooks, who has a longstanding relationship with Bigby and helped former Knicks standout Tyler Bey earn a scholarship to Colorado and become a 2020 second-round NBA draft pick.

All Robinson had to do was awake every day at 4 a.m. and comply to a militaristic regimen designed to develop college basketball players. Not that he had a problem with that.

“He had a thirst to learn,” Middlebrooks said. “He wanted to be good.”

Meaning Middlebrooks wouldn’t have to summon Robinson to the gym or practice.

Robinson was a fixture in the weight room and on the basketball court, focusing specifically on the nuances that modern big men must master. When Robinson returned bigger and stronger to Las Vegas the ensuing spring for one final club campaign, Bigby and his coaches recognized his improvements and installed an offense that would augment his evolving set of skills.

One scholarship offer became 30 amid stellar performances against five-star big men like Evan Mobley and Charles Bassey. Even blue bloods like Kansas and Louisville came calling.

‘Totally positive’

But they couldn’t offer the promise of playing time the way Fresno State’s Justin Hutson could. The former UNLV assistant was hired that spring to his first collegiate head coaching position and prioritized Robinson’s recruitment the first time he watched him play in person.

The offers would mount, but so, too would Robinson’s trust in Hutson, who promised Bigby that he would employ some of the same offensive actions the Knicks ran for their point center.

“He did exactly that,” Bigby said, and the Bulldogs would be the beneficiaries.

Robinson bypassed the blue bloods in favor of Hutson and Fresno State, selecting the Bulldogs from a pool of finalists that included Georgia Tech and Boise State. Another year at Middlebrooks Academy helped ease Robinson’s transition into the Mountain West.

He would lead Fresno State in scoring as a freshman, averaging 12.2 points and 6.6 rebounds to ignite the program’s rebuild and spur Hutson’s continued belief that he’s an NBA player.

Hutson believed so from the onset. “You just had to steer him the right direction,” he said.

Sometimes that meant barring Robinson from the gym, where he’d toil during his free time even deep into the season. Prevent him from practicing and he’ll direct his energy into something else productive.

He doubled as an All-Conference academic, after all. His competitive nature extends beyond the confines of the basketball court and into whatever he decides to do.

“No matter what it was, he has always wanted to be successful in it, no matter if it was writing an essay or doing good on a test,” said Fresno State guard Anthony Holland, Robinson’s best friend on the team. “It’s pretty contagious. It’s like ‘If that dude can do it, I can do it, too.’”

As Robinson improved, so, too did the Bulldogs. From 11-19 during his freshman season to 12-12 as a sophomore to 23-13 during the 2021-22 season, his final at Fresno State. He averaged 19.4 points and 8.4 rebounds, unearthing a feathery 3-point shooting stroke that could prove invaluable at the next level.

Forgoing a final year in Fresno seemed inevitable, but Robinson still wrestled with the decision to leave, feeling unfulfilled because the Bulldogs didn’t win the Mountain West or reach the NCAA Tournament during his tenure.

Nonetheless, he prepared for the NBA draft in Los Angeles, auditioning for nearly half of the NBA’s 30 teams after attending its scouting combine. Some mock drafts had Robinson as a late first-round pick. Others completely ignored him.

Robinson Sr. said he “had a feeling something wasn’t right” as the draft began. But Robinson remained “cool and calm” as the proceedings unfolded, thereby calming those around him.

“He had a totally positive attitude,” Middlebrooks said,”and he understood ‘Hey, I’ve been digging out of the mud the whole time. We’ve got to keep the same thing going.’”

One day after not being drafted, Robinson went to the gym — knowing his contract with Miami guarantees him an invite this fall to training camp and little else in the NBA this season.

He could spend time with the Heat’s G League affiliate in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, as he improves as a rim protector and 3-point shooter, two self-identified areas for growth.

Improvement doesn’t intimidate Robinson.

Then again, nothing does.

“Because of the person he is, that’s what makes him a professional basketball player,” Fells said. “Who he is on the inside, it can translate on the physical side and produce that level of operating on the basketball court. … That’s kind of how he stays settled.”

Contact Sam Gordon at sgordon@reviewjournal.com. Follow @BySamGordon on Twitter.