These snake lovers cruise Nevada’s roads at night for reptiles

For Bob McKeever, all of the fun starts right before sundown.

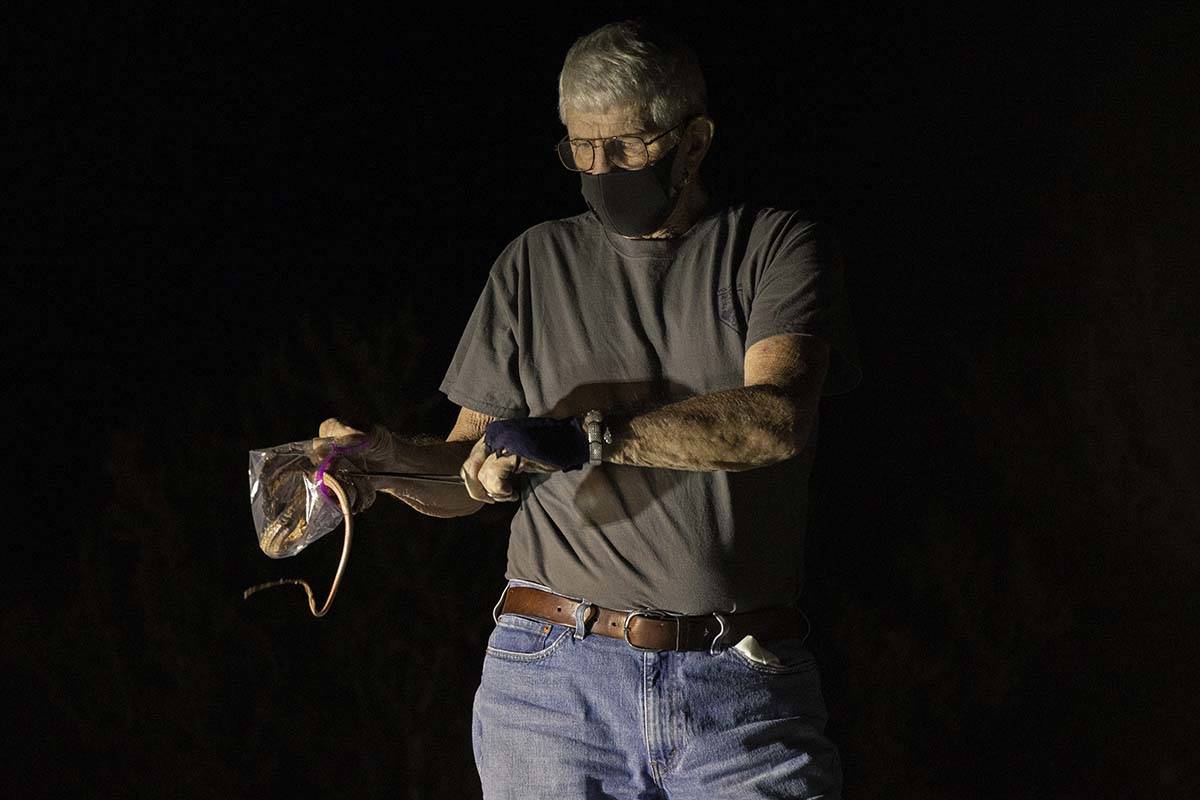

McKeever, 77, is one of 16 volunteers helping Nevada’s state herpetologist, Jason Jones, cruise the roads of the Mojave Desert for reptiles.

From April to October, Jones assigns weekly volunteers to drive along point-to-point stretches of road called transects from sunset to well after midnight. They’re watching for any snakes and lizards to help determine population numbers.

McKeever has been road cruising since the 1970s when he started working for the National Park Service. But his love for herps (reptiles and amphibians), started long before then.

“I am in my 70s and it started when I was a little kid back in Pennsylvania. I was introduced to wildlife of virtually all categories — birds, mammals, reptiles and so on — by my parents. I just was attracted to snakes, I guess because nobody else was,” McKeever said.

Last week, the two men, who adhere to social distancing in separate cars, met at the gates of Red Rock National Conservation Area.

After making sure their walkie-talkies were on the same frequency, McKeever started driving along the scenic loop. Jones took off 15 minutes later, so he could spot anything McKeever missed.

McKeever said the best speed is around 25 mph. “Some folks drive a little slower, some a little faster, but I think a slow speed is the most effective.”

They cruised along each transect twice. If they saw a snake or lizard, they pulled over, recorded what they saw in a notebook and then helped the critter off the road.

“Roads are an easy method for finding the snakes in particular and some of the nocturnal lizards,” Jones said. “The scaly creatures really stick out against the asphalt, whereas if you were walking in the desert with a headlight, they’d be almost impossible to find at night. The main defense for many reptiles is to blend in with their natural environment.”

After more than two hours of driving, Jones and McKeever thought the night was going to be a bust after the first pass yielded only one gecko, one night snake and a dead coachwhip.

But at 10:26 p.m. on the last pass, Jones radioed to McKeever that he had another night snake.

McKeever sped to meet up with Jones, and when he got there, he got a surprise. While Jones was making notes about the second night snake, a rarely seen Smith’s black-headed snake slithered onto the road.

As a lifelong herp enthusiast, McKeever said he was beyond delighted because there were probably fewer than 100 people in Nevada who have seen it. Not only is this snake tiny, less than a foot in length, it spends most of its life underground.

Jones and his volunteers spend hundreds of hours on the same eight transects to see how the populations of these reptiles change over time in Southern Nevada. Some nights volunteers come up empty-handed, and other nights they find a variety of animals.

Cruising just one option

Road cruising is only one of the methods herpetologists use to determine reptile populations.

“While it’s kind of a mediocre technique to find snakes, it has served its purpose in terms of documenting the species assemblage and who is here now, and how will that change in the future, given climate and habitat change,” Jones said. He goes on to compare searching for herps to looking for a moving needle in a haystack.

When most people think of reptiles, they think of cold-blooded animals that need the sun to heat up and function (thermoregulation). But when the sun makes it too hot to properly thermoregulate during the day, they may come out at night to heat up on the roads. Other times, snakes are just crossing the road to get to the other side.

This work can be dangerous. “If you’re driving surveys, you always have to be aware of vehicle traffic,” Jones said.

It’s not just professionals cruising the roads for herps in Nevada.

Many enthusiasts spend countless hours in the Mojave Desert searching for the elusive creatures. “There is a real interest in herpetology across the country and actually around the world. There are people who travel here from European and Asian countries to do these — the road survey thing we’re talking about; they’re just doing it on their own to add to their life list of reptiles just like a birder would keep a life list,” McKeever said.

Observations by hobbyist herpers are incredibly useful for identifying areas where certain species may be found, which aids in establishing transects.

Some transects are identified by previous studies. For example, Red Rock is a transect that has been studied for over 20 years to monitor reptile populations.

Other sites are chosen by the Nevada Department of Wildlife because they have the right habitat, such as types of plants, elevation and size of rocks. The department has a Wildlife Action Plan that aims to preserve animals and habitats that have the highest conservation need. Knowing which habitats a species lives in helps cut down on time spent looking for it.

Snakes are important to the ecosystem because they eat anything from termites to mammals and are key to managing rodent populations, which are vectors for disease.

Beyond their ecological benefits, both Jones and McKeever get a thrill every time they see a new or favorite species. “I think road cruising is really fun because you’re in total darkness minus what you can see with your headlights,” Jason said, “You never know what’s around the corner, and when you see a big snake out across the road, it’s one of the coolest things that I’ve experienced.”

The surveys that Jones runs are purely observational.

He said new reptile enthusiasts should always be vigilant of traffic and local laws regarding interactions with animals. Some species, such as the rosy boa, are protected by the state, which makes it illegal to handle them or otherwise remove them from the environment.

New enthusiasts are encouraged to record any observations they make in apps such as iNaturalist or Herpmapper. These apps share the data collected with scientists like Jones. It’s an easy way to make a significant contribution to science, Jones added.

Jones is always seeking new volunteers. Those interested can learn more about opportunities through the Nevada Department of Wildlife on the volunteer webpage.

McKeever says he’s had some sightings he would not have had without the road surveys.

“I found a black-headed snake one night that had been captured by a scorpion. Unfortunately, both got run over by a car, but then I found another scorpion eating a lizard. I encountered a pair of speckled rattlesnakes during a combat ritual dance. And believe it or not, they’re all exciting to me.”

Earyn McGee is a 2020 Mass Media reporting fellow through the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Email her at emcgee@reviewjournal.com. Follow her on Twitter at @Afro_Herper