New NASA mission explores planets, stars beyond solar system

Look up at the night sky.

If you did that in the early 1980s, you might have speculated. You might have guessed.

But you wouldn’t have been certain if planets existed beyond our solar system.

At the time, NASA’s Kepler mission was just an idea from scientist Bill Borucki. But after the mission launched in 2009, it contributed significantly to the understanding of exoplanets — planets that orbit a star other than the sun.

“We opened up a box expecting to see something, and there was something entirely different inside,” said Jason Steffen, a member of the Kepler Science Team and an associate professor of physics and astronomy at UNLV.

Changing perceptions

Steffen joined the Kepler team in 2008, about a year-and-a-half after he finished his doctorate from the University of Washington.

“I was a post-doc, which is the science equivalent of a medical residency — a doctor, but a ‘rookie’ doctor,” he said. “I joined the science team to do studies of the orbits of planets and how the planets interact with each other. I developed a technique as a grad student that was useful for the Kepler data.”

The mission had significant findings, Steffen said.

“There are at least as many planets in the galaxies as there are stars, and probably more than that,” he said. “There are probably more planets than there are stars.”

Some planets, Steffen said, follow orbits that are only a few hours long.

“They go around their stars a few times a day,” he said. “It’s so hot that the rocky surface is evaporating off the planet.”

They also found planets that orbit two stars at once.

“Those are quite a bit harder to find,” Steffen said. “There’s at least 10 systems that have been found, but they’re so hard to identify that there are undoubtedly many that have been missed.”

Kepler is a spacecraft housing a 1-meter telescope that illuminates a 95 megapixel digital camera the size of a cookie sheet, according to an article published by Steffen. The instrument detected tiny variations in the brightness of 150,000 distant stars, looking for the telltale sign of a planet blocking a portion of the starlight as it crosses the telescope’s line of sight, Steffen said.

Overall, the number of planets known to orbit distant stars grew from under 100 to more than 2,000 in the past 10 years, Steffen said, with another 2,000 likely planets awaiting confirmation. Most planets that Kepler discovered are two times Earth’s size, and about five times its mass, he said.

“It’s certainly changed our perception of what planetary systems look like,” Steffen said. “Very few of the planets that were discovered by Kepler look like planets in the Earth’s solar system.”

Closer and brighter

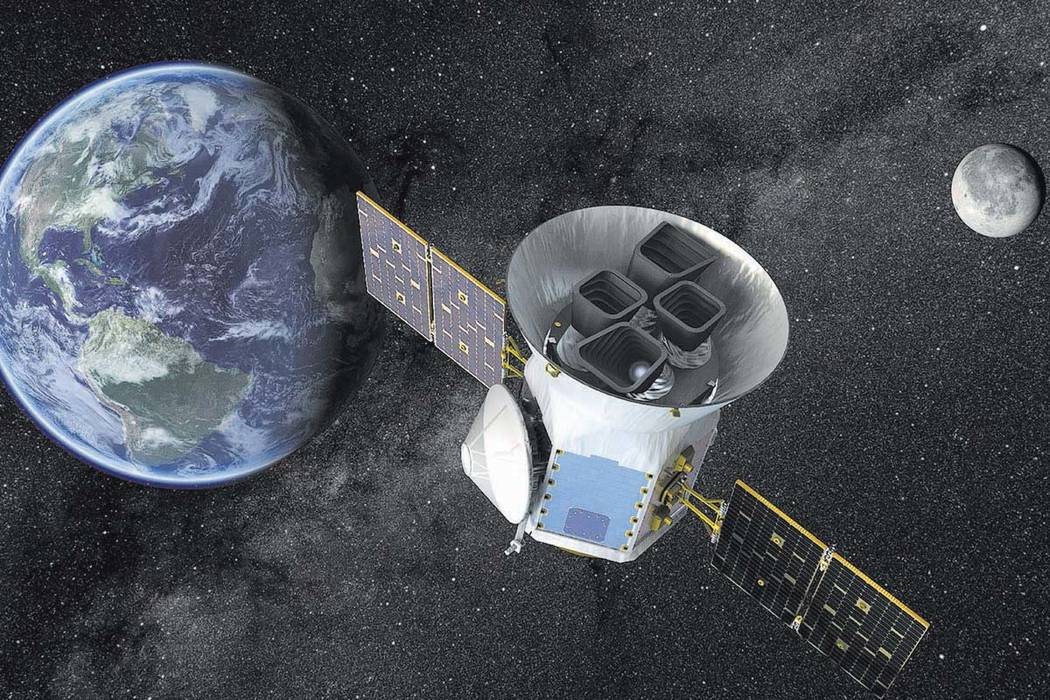

The Kepler mission is powering down, but it leaves room for a new space exploration: the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS.

TESS is set to launch Wednesday from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station and will add to the body of knowledge and data collected by Kepler, Steffen said. He’s part of a working group that will study TESS data.

“You run Kepler first, and that informs the design of the TESS mission,” Steffen said. “We can use TESS to be able to connect Kepler observations to future observations of other instruments.”

The TESS mission will identify planets ranging from Earth-size to gas giants, using an array of telescopes. It differs from Kepler in that the planets they’ll be looking for are brighter and closer than those identified by Kepler.

“The issue with Kepler was that most of the systems we discovered were pretty far away — 1,000 light years away, not in the solar neighborhood,” Steffen said.

“The Kepler targets were farther away, and as a consequence, dimmer. TESS is designed to look at the brightest stars that are close by.”

TESS will conduct at least a two-year survey of the almost the entire sky, Steffen said, with the ability to extend it up to five additional years depending on the fuel.

“As long as the cameras keep functioning, we’ll keep using it until they can’t steer it anymore,” Steffen said, adding that as soon as the data are analyzed on the ground, they will be released to the public

Zhaohuan Zhu, an assistant professor of physics and astronomy at UNLV, said the TESS mission will have implications for his research.

“It will be able to help us understand how planets formed in our universe,” Zhu said.