Martian rocks from rover mission may come to Las Vegas first

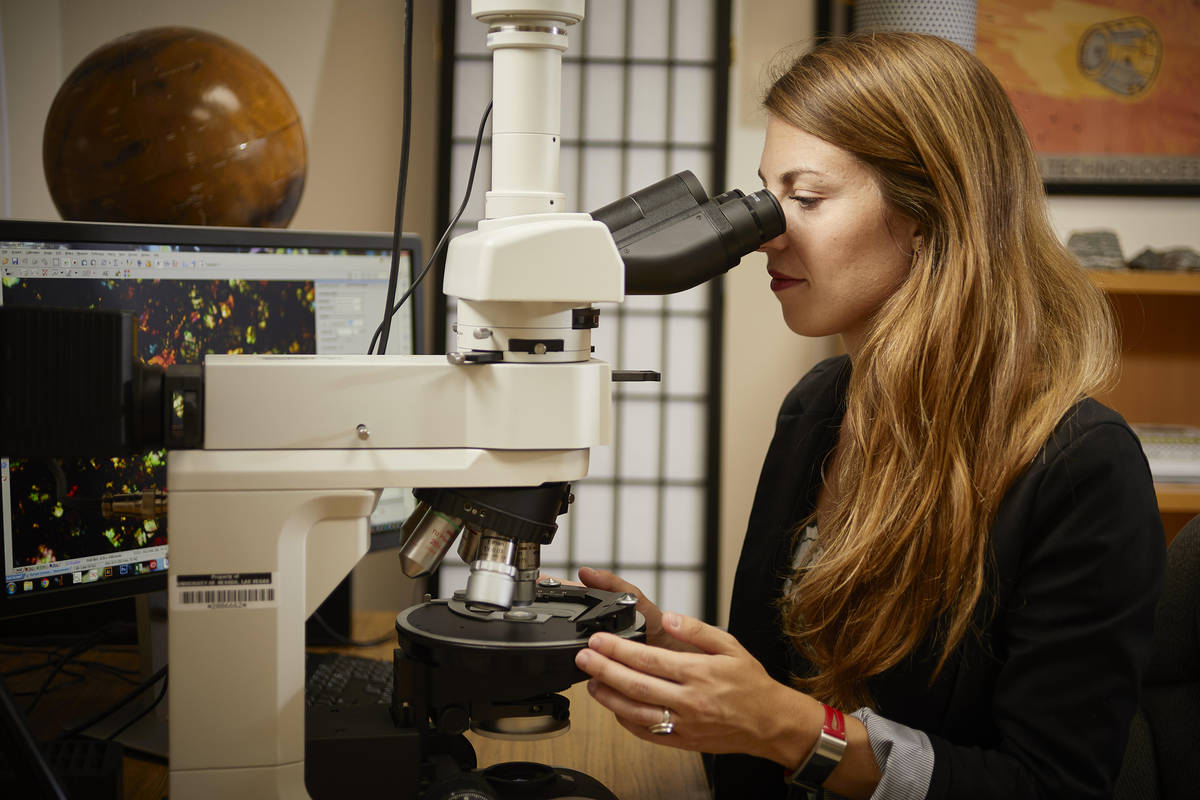

If the Mars Perseverance rover was lifting off from Cape Canaveral at almost any other time, UNLV Professor Elisabeth “Libby” Hausrath would have had a front-row seat.

But in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Hausrath, one of 10 scientists selected by NASA to study the soil and rock samples that will eventually be returned to Earth from Mars, will be watching from home when the rocket carrying the rover is launched.

That could happen as soon as 4:30 a.m. Thursday or in the following days, depending on weather and other launch conditions.

“It’s really too bad, but I’m super excited, whether I’m in Florida or not,” Hausrath said.

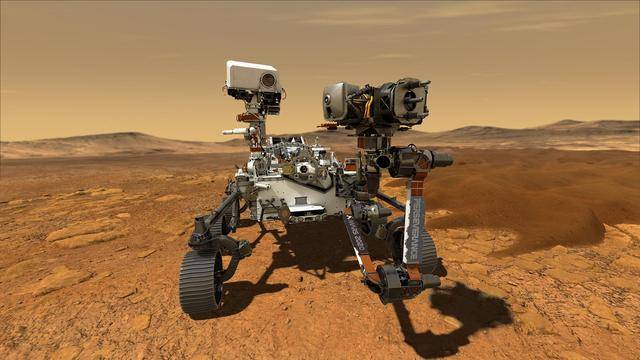

The 2020 Mars mission will be the first to return to Earth with Martian rocks to be analyzed in laboratories beginning in 2031.

Hausrath is not the only scientist at UNLV who is deeply invested in better understanding the red planet. From geology to human health, researchers in our backyard may help unravel the mysteries of our planetary neighbor and even pave the way for humans to one day make the more than 100 million-mile round-trip journey.

Previously, the only Martian rocks that geologists have been able to study in person are those that made it to Earth on their own, as meteorites.

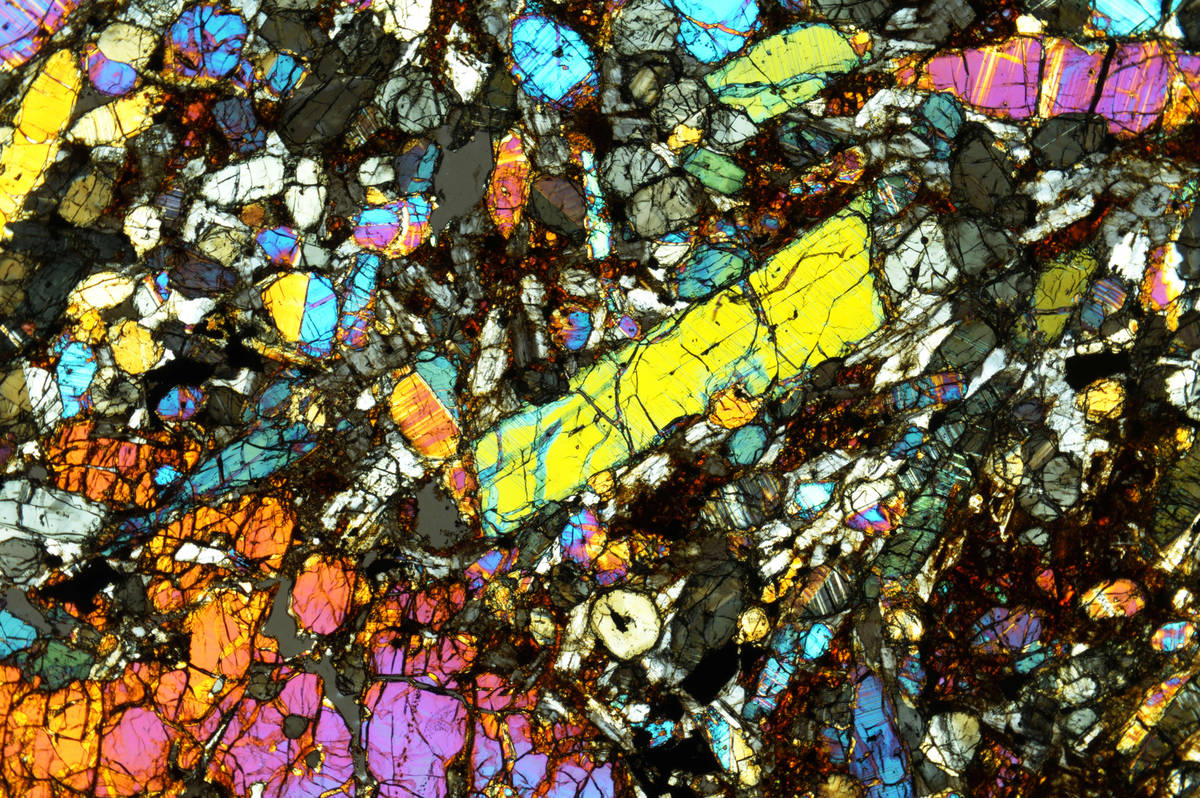

Arya Udry, a professor of geology at UNLV who studies Martian meteorites, said their chemistry and composition provides glimpses into the planet’s ancient past and how the movement of magma on and below the surface influenced the planet’s geography, much as happened on Earth.

“For the moment … meteorites are the only samples that we have from Mars,” Udry said. “We can analyze them in the lab using the same tools, the same instruments, with which we analyze Earth samples to better understand the chemistry, what kind of minerals they have, what are their ages, when were they ejected from Mars. … And all that ties back to the evolution of the planet.”

Limited supply of meteorites

Meteorites have fallen to Earth throughout time, but only a small fraction of them came from Mars. It is believed that there are currently fewer than 200 rocks being shared by Mars geologists. And since their analyses often require cutting very thin slices or using a pinch of finely ground powder to examine the chemical structures, eventually these will be depleted. At that time, scientists will either have to find more Martian meteorites or collect samples from the planet itself.

The samples returned from the Mars mission will provide an unprecedented glimpse into the planet’s geology, untainted by a tumultuous and random journey through space and potentially years of sitting in a desert on Earth, said Udry, who will have to apply for access to a tiny sample of the specimens.

Hausrath, on the other hand, will be one of the first to study the fresh Martian rocks.

Though also a geologist, Hausrath studies the way that rocks interact with water. Signs of water are evident on Mars, including the presence of valleys and patterns in the dirt discovered during past Mars missions that suggest the planet’s now-hostile environment may have once been suitable to sustain life. No rover, however, is capable of doing the complex experiments that scientists can do on Earth.

“Mars 2020 is really interested in looking for assessing possible evidence for past life,” Hausrath said, “and that’s one of the reasons why samples are so important, because definitively identifying that would probably only be possible in a laboratory on Earth.”

Only about 31 rock samples, less than a pound total and each roughly the size of a pencil stub, will return to Earth.

Like the meteorites, any scientist interested in studying them will have to share. In the meantime, NASA’s team of scientists will be monitoring data sent back by the rover to carefully choose which samples will make the return journey.

Much of the data relayed from state-of-the-art instruments on the rover itself will eventually become publicly available.

Though not directly involved in the NASA mission, scientists like Udry and UNLV professor Christopher Adcock will be able to use that to do computer modeling and answer their own questions about Mars geology.

Building blocks for life

Adcock, a planetary geochemist, is one of many scientists investigating the chemical building blocks for life, in his case, phosphates. Phosphates are required for life to occur in a few crucial ways, including holding DNA together and acting as a key ingredient for metabolism.

“It has some very unique properties that make it irreplaceable, so to speak,” Adcock says. “We can’t really use other compounds to substitute for it.”

Phosphates, chemical compounds that contain phosphorus, come from rocks and minerals. Adcock uses data gathered by previous Mars rovers, including Spirit and Opportunity, to create computer models to discover how phosphates transform over time.

“The phosphates are locked up inside minerals, so we study how it gets out of those rocks and into the environment so that it could possibly be overtaken by biology,” Adcock said. “Things can take a really long time in nature. So we put them into models so we can speed them up.”

While Adcock examines whether life could have previously existed on Mars, other researchers are dedicated to making the distant planet habitable for humans, at least in the short term.

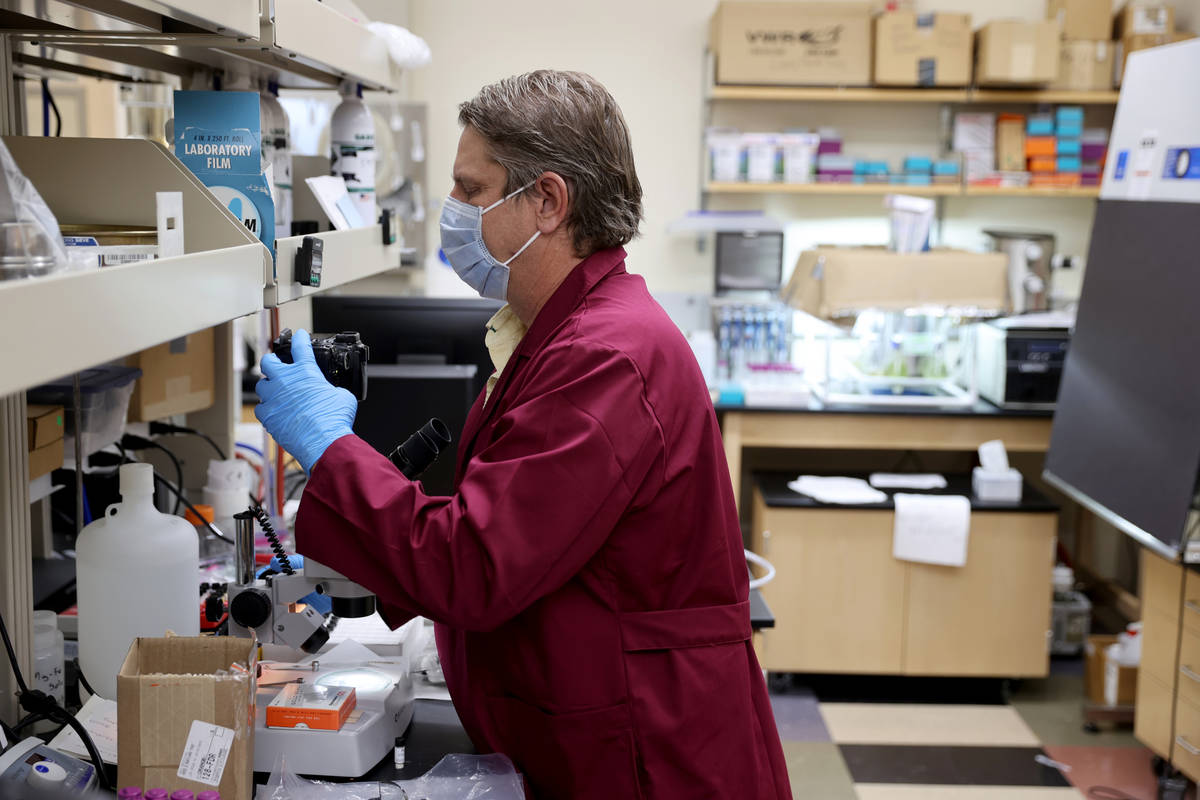

Francis “Frank” Cucinotta, a professor in the Department of Health Physics at UNLV, studies only one of many dangers deep space poses to humans: radiation.

The effects of radiation on Earth, from, for instance, a nuclear explosion, are most commonly associated with cancer, but astronauts will also be at risk of brain damage when exposed over the years a Mars mission would take.

Calculating radiation danger

Cucinotta is most concerned with cosmic radiation, essentially atoms that move through space at close to the speed of light. Unlike solar radiation, blocking cosmic radiation would require a barrier at least hundreds of inches thick. Earth’s atmosphere, hundreds of miles thick, keeps this dangerous radiation away from us.

Cucinotta’s research suggests that the risks of developing cancer and cognitive issues during deep space travel is greater than originally thought.

“NASA and other space agencies have limits to how much cancer risk an astronaut is allowed to have,” Cucinotta said, noting that for long, deep space missions like the one to Mars, the exposure to dangerous radiation could be as much as five times higher than any of NASA’s past manned missions.

Planning space missions around risk poses a serious ethical dilemma for NASA, which may have to change its risk tolerance or invest in technology to reduce the danger, Cucinotta said.

We may not have answers to whether there has ever been life on Mars or if humans will be able to support themselves there for many years. Such questions — whether about chemicals like phosphates or how water interacts with the planet’s surface — are puzzle pieces that will eventually fit together to finally answer those and other cosmic quandaries.

“Proving that there is life on Mars or there has been life on Mars is not something that will probably come with a single discovery,” Adcock said. “It will most likely require a large number of smaller discoveries.”

But with a critical mass of Mars geologists working together to study the planet from different angles, the answers to those questions may come sooner rather than later.

“Planetary science in general is one of those sciences that almost requires an interdisciplinary approach,” Adcock said. “We’re dealing with instruments. We’re dealing with natural physical materials like rocks and soil. We’re dealing with meteorites. We’re dealing with chemical experiments. … We bring them all together and then we can solve problems that on our own we probably wouldn’t have been able to solve.”

Marina Philip is a 2020 Mass Media reporting fellow through the American Association for the Advancement of Science. Email her at mphilip@reviewjournal.com. Follow her on Twitter at @mureeenuh.