WWII vet recalls duty as guard at Nazi trials

Like fireworks on Independence Day, Alex V. Lopez celebrated his 19th birthday with a burst of machine-gun fire on the day the United States and its allies restored freedom to Europe, held in the grip of Nazi Germany in World War II.

“I was at a machine-gun nest outside the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, and it was May 7th, which was my birthday, and they announced that the war was over. I opened a clip on the machine gun up in the air,” Lopez said, recalling the day in 1945.

Now 86 and living in Las Vegas, Lopez was an Army private who had arrived in France in mid-January 1945 in time to fight the last days of the Battle of the Bulge with the 79th Infantry Division. His unit, the 314th Infantry Regiment, cleared towns in northeastern France and drove Nazi soldiers out of Haguenau Forest and back across the Rhine River into Germany.

But it wasn’t those battles that put Lopez in history’s spotlight.

That came months after he shed his battle fatigues and turned in his machine gun. His old unit was packing up to return home when the Nuremberg trials started Nov. 20, 1945.

“When the war was coming to an end, I didn’t have enough points to come home, so they sent me over to 1st Division,” said Lopez, a draftee from Los Angeles who was one of only a handful of Mexican-Americans in the 79th Division.

“My commander came to me at the barracks and told me I had to get myself all pressed up, my clothes cleaned and shined and everything, and go to the Nuremberg trials and report to a lieutenant.”

Lopez donned the white helmet, belt and gloves and pressed dress uniform, pants tucked neatly into his black leather boots – the signature uniform of 1st Infantry Division military police who were courtroom guards at the Nuremberg war crimes trials.

NUREMBERG GUARD

Preparing his uniform was no easy task.

“I had to take my brown belt, put salt on it and put it out in the sun so it would turn white. I had to put wax inside my seam to iron my clothes. I had English boots, which is leather all the way up with hobnails in the bottom of them. And I had to shine them every day. And, I had to press my shirt, my pants every single day,” he said.

Allied officials were looking for a tall combat veteran to guard Hermann Goering, Luftwaffe commander and Gestapo founder and one of the highest-ranking Nazi officials.

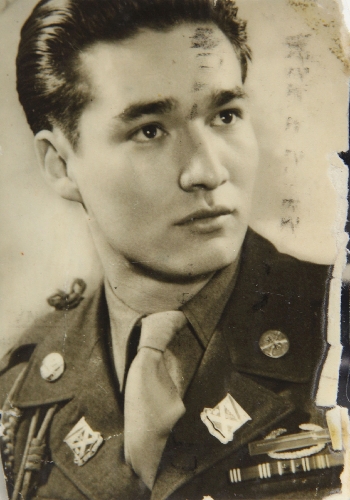

Clean-shaven Pvt. Alex Vincent Lopez, with his chiseled chin, high cheekbones and no-nonsense brown eyes peering from beneath his white helmet, fit the bill.

In his wallet, Lopez still carries a photograph from the trials. It shows a 20-year-old Lopez standing at parade rest behind Goering, who is seated at a microphone wearing a double-breasted olive jacket with a perplexed look on his face. Behind them is a wooden wall hiding an elevator shaft for bringing prisoners from their cellblocks to the Palace of Justice auditorium.

Occasionally, Lopez would watch Rudolf Hess, Adolf Hitler’s deputy. But for most of the nine months he served during the trials, he guarded Goering.

Eventually they got to know each other to the point they would sometimes chat in English.

“He could speak it enough to understand what I said,” Lopez said. “As a matter of fact, he asked me what my nationality was. He didn’t understand ‘Mexico,’ so that was it with him.”

Once, Goering autographed a dollar bill for him.

But it was all business in the courtroom, where translators would convey conversations among judges, lawyers and prisoners using microphones and headsets.

“One day he took his earphone apart, and there was a sharp instrument in there. I had a BB sap that big,” Lopez said, holding his hands about a foot apart to show the length of a flexible baton tipped with lead shot. “I hit him over the hands with the BB sap, and he called me a ‘schweinehund’ ” (literally, pig dog).

For the most part, despite his arrogance, Goering was “a real congenial person,” Lopez said.

At night, Goering’s bad side would erupt.

“Goering was, I’m sure, a dope addict,” Lopez said. “About four in the morning he’d start screaming and hollering, moaning and groaning. He couldn’t take it anymore.

“So they’d take him out and strip him down and check him out and give him a shot. And then he’d go back into his cellblock. I understand he had a heroin field in back of his house.”

Historians note that Goering, a decorated World War I pilot, became hooked on morphine after he was shot in the leg during a failed coup attempt by Nazi party leaders in 1923.

Despite being tried for war crimes and crimes against humanity, including starving Jewish civilians, the Nuremberg prisoners ate well, Lopez said.

“They had some pumpernickel bread that you’d die for. I used to steal it from them,” he said. “Then in the mornings they had a bunch of fruits and cereals and all this sort of stuff, and they had stews.”

SENTENCED TO DEATH

Lopez returned to the United States and was honorably discharged at Camp Beale, Calif., on July 31, 1946, less than three months before Goering was found guilty on all charges and sentenced to death. But the night before Goering was to be hanged, he ingested a potassium cyanide pill and quickly died.

In 2005, another courtroom guard, Herbert Lee Stivers, said he was the one who slipped Goering the suicide pill.

But Lopez believes it was the Army “captain” with sole access to Goering’s cell who gave him the deadly pill.

“There was only one guy that got next to him. From what I hear, he asked this guy to go into his briefcase and get him a compound that he had there, some kind of cream compound. The pill was inside that compound,” Lopez said.

Authors who researched the suicide identified the U.S. Army officer as Lt. Jack G. Wheelis, who died eight years after Goering died. He sneaked the pill to Goering in exchange for souvenirs, including Goering’s watch, which Wheelis is seen wearing in a photo after the war.

COMBAT OVER GUARD DUTY

Looking back on his minor role in military history after the war in Europe ended, Lopez said his combat experience overshadows the tedious duty as a courtroom guard.

Lopez lives day by day with his one year, 11 months and 10 days in the Army – from a bout with frostbitten feet to his first encounter on snowy battlefields in Alsace-Lorraine. “They sent me out at night, and I stepped on a dead Kraut in a white uniform.”

He said he remembers killing only one enemy soldier, a sniper in Nancy, France, from whose body he retrieved a P-38 Luger pistol. But his descriptions of battle suggest many more.

“We were more-less an attack division. We would attack every Sunday, and a lot of times we would go back and take a town that we already took once,” he said. His .30-caliber, air-cooled machine gun was “a long sucker that you’d set up in a foxhole. I carried it on my shoulder. I had two ammo bearers behind me.”

Lopez can’t erase some memories, such as the time in Czechoslovakia when his regiment was under attack.

“I didn’t care who I was firing at, I was just firing,” he said. “Those guys were crazy, man. They’d come right up in front of you, and you’d just cut ’em in half. Terrible.”

In the northeastern tip of France, he was told to shoot only five-round bursts.

“And that’s what I tried to do, especially when we were under attack in the Haguenau Forest. It scared me because I shot 10 rounds one time because they were almost on top of me.”

He said his worst experience was crossing the Rhine. Sixteen heavy artillery guns had cleared the opposite shore.

“You wouldn’t believe the horrible scene you were seeing over there. … The shooting was more or less over, but it was still a mess,” he said. “You get 16 rounds going through over there, and you see dead people. That was horrible, horrible, horrible. I’ll never forget that scene. I couldn’t get out of there fast enough.”

BADGE OF HONOR

While the phrase “post-traumatic stress disorder” wasn’t in the soldier’s vocabulary during World War II, PTSD certainly became a reality.

“I dream about it once in a while, and it sort of gets you a little bit,” Lopez said. “You get flashbacks on it, but you wake up and walk it off.”

Lopez points to the Combat Infantryman Badge – light blue with a silver musket – pinned to his black “World War II” cap.

“That means more than damn near all the medals those generals have on their coats,” he said. “I was under fire. People were trying to kill me. That’s the best medal you can get as far as I’m concerned.”

Today, on the nation’s 236th birthday, Lopez intends to observe Independence Day more closely than in past years and pause to remember the freedoms he defended. He thinks some of them are slipping away after patriotism surged on the heels of the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

He told his sons to never drop their guard.

“For this nation to be going the way it is going, and the way I see it, I’m going to have a gun in some hole in Las Vegas defending this country again. That’s the way I feel about it.”

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@

reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.