WWII memories remain vivid for Navy veteran, 91

Navy Lt. Leonard Gross arrived at Pearl Harbor two years after the attack to work for “God.”

That’s how he described Adm. Chester W. Nimitz, commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific fleet.

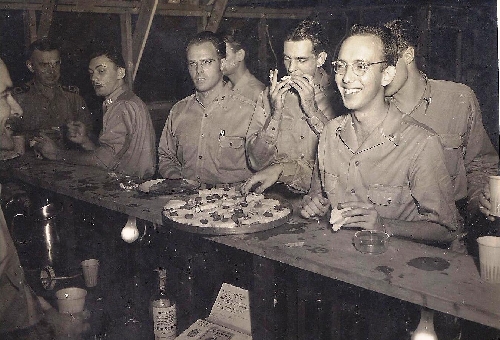

Gross had shaved his black, pencil-thin mustache that he had grown while sharing a Quonset hut with fellow officer and future author James A. Michener on the island of Espiritu Santo before leaving on the three-day flight to Hawaii.

When he reported for duty at Nimitz’s office on Oahu, the legendary admiral answered the knock with a resounding, “Come in.”

“I started to shake,” Gross, 91, recalled in a recent interview at his Las Vegas home. “I was so scared. I was 22 years old, and I’m going to meet with ‘God.’

“Admiral Nimitz was so worshipped in the fleet because he was just a great officer and a great man,” Gross said.

“I walked in there, and he could see how scared I was. He said, ‘Son, you’ve got nothing but friends here. Sit down.’ ”

Then Nimitz got him a cup of coffee while Rear Adm. Forrest Sherman, Gross’ shipmate from the sunken USS Wasp, stood by to hear Nimitz discuss his plan.

“We’re through on the defense. We’re now going on the offense. We’re now going to win this war,” Nimitz assured them.

“We need somebody who’s going to write the communications section of the operations plan for the next series of invasions.

“Sherman thinks you can write that. Can you?”

Gross pondered the question.

“I hadn’t the vaguest idea what the hell an operations plan looked like. At that point, I looked him straight in the eye and said, ‘Admiral, I can do it.’ ”

For the next year, he would bang out dozens and dozens of pages. He defined the radio frequencies and outlined procedures that destroyers, battleships, aircraft, landing craft, troop carriers, commanders and Marines would use to communicate for the series of invasions on Japanese strongholds from Kwajalein and Enewetak in the Marshall Islands to Guam, Tinian and Saipan in the Marianas. All aspects were spelled out from ship-to-ship, ship-to-shore, air-to-air, ship-to-plane and plane-to-plane, including backup and emergency frequencies.

As a junior officer since the onset of the war, Gross was immediately promoted to lieutenant commander so he could sit in on the secret battle briefings.

He was a teenager when he joined the Navy in Philadelphia to become an ensign as a “90-day wonder.” But now he was a veteran of the hell of war, from the time he swam for his life in an ocean on fire off Guadalcanal to the emptiness in his heart when he found out his former midshipman roommate in Chicago, Charles Taylor, had perished when the battleship Arizona sunk after Japanese warplanes bombed it at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

Gross has never forgotten that day. It was Sunday. He was taking a nap on the USS Wasp more than 5,500 miles away in the Atlantic at Grassy Bay, Bermuda. Almost all the officers and men were ashore on liberty, except for him and 12 Marines.

His radioman banged on the door. “Mr. Gross. Wake up! Wake up! They bombed Pearl Harbor!”

“I said, ‘Oh go away. Don’t give me that crap.’ And he said, ‘It’s true. It’s true.’ ”

Gross was now wide awake. “I knew we had to get the hell out of Bermuda Harbor as quickly as possible,” he said.

He sent two Marines to find the captain and the executive officer. The other 10 Marines roamed the streets, calling for all crew to return immediately.

Within three hours, they were underway , heading to confront an Axis, German U-boat base at Martinique in the French Caribbean until orders came not to attack Martinique but instead steam toward Norfolk, Va., pick up an air group and join the British fleet in Scotland.

The war was waging in North Africa, and the British were struggling to keep their planes flying out of the Mediterranean island of Malta, a key base for attacking Axis ships that were supplying German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s armored Panzer division with fuel and reinforcements from Europe. As a result, German and Italian warplanes were constantly bombing the island.

The Wasp had twice evaded German ships and planes in attempts to deliver 80 British Spitfire aircraft to Malta. The first batch was destroyed in bombings, but the second batch survived and proved vital to cutting off the Axis supply lines to North Africa.

Soon after, Gross received a coded dispatch. He woke up the captain, who announced over the ship’s speakers, “Now hear this. We have just received a dispatch. It’s addressed to the officers and men of the Wasp. ‘Who says that a Wasp cannot sting twice. Signed: Winston Churchill.’ ”

“What a cheer went up. That dispatch is in the Navy archives,” Gross said.

From there the Wasp headed to join the war in the Pacific. From the Panama Canal, it headed north to San Diego to lead the Guadalcanal campaign. On the third morning out of San Diego, Gross stared at the horizon.

“As far as I could see the whole ocean was covered with ships. There were three aircraft carriers. There were battleships, heavy cruisers, light cruisers, destroyers, supply ships, attack transports. As far as you could see were these ships.”

After the Guadalcanal invasion on Aug. 7, 1942, Rear Adm. Leigh Noyes put the ship on a predictable, straight-line patrol course which, in retrospect, was a fatal decision for 193 sailors on the Wasp.

“Every day at the same time we were at the same place going at the same speed on the same course. We were making bets when something was going to happen.”

And it did, about 3 in the afternoon on Sept. 15, 1942, when the ship’s aircraft were being refueled with some of the 100,000 gallons of gasoline on board.

As the ship’s secretary, Gross was writing the war diary while broadcasting a classical concert over the ship’s speakers. About 30 seconds into Schubert’s “Unfinished Symphony,” two torpedoes from a Japanese submarine struck the Wasp and exploded.

“It was violent. The hangar deck was a wall of fire,” he said, recalling how he, his roommate, R.H. “Snuffy” Smith, and 50 enlisted me were cut off from the rest of the ship.

“We had the men take their shoes off and line them up on the deck. We knew we were going to have to abandon ship.”

A radioman handed him a life jacket. The two officers were the last ones to descend a line to the water 50 feet below.

“It just wasn’t my time to go yet,” he said. “I was in the water for six hours with the surface burning all around me. It was just dreadful, the ship blowing up and the flames got to each one of the ammunition dumps.”

Gross was the last man picked up at dark. He had third-degree burns on his face, hands and back, “and I had swallowed some oil. I was a mess.”

“And they threw me on a pile of dead bodies in the forward part of this motor whale boat. When they got to the ship (the USS Lansdowne), the officer on the deck called down to the coxswain and said, ‘What are those bodies up there?’ And the coxswain said, ‘They’re all dead.’ But just then, the oil that I had swallowed made me throw up. And they said, ‘He’s not dead. Get him out of there.’ ”

Gross and 34 others were taken to a base hospital 600 miles away on Espiritu Santo where his burns were treated with sulfanilamide powder and beeswax to prevent scarring.

In 1990, he returned to Pearl Harbor and visited the USS Arizona Memorial.

“When they had that video of what happened to the Arizona, when that first explosion went, I just went ape. I had to walk out of there,” he said.

“It’s the same thing every time I hear Schubert’s ‘Unfinished Symphony.’ When I hear that note, exactly when the first torpedo hit, I start to shake. … It’s not a reaction that causes me to go into any kind of trauma. It’s a remembrance. You remember those things.”

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.