WENDOVER, Utah — The son leans in first, the father behind him. Slowly, they slide open the towering 24-foot-high door to the old airfield maintenance hangar, putting their backs into the mission like the U.S. Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima.

Then Jim Peterson and his adult son Tom stand back as 30 visitors file into the cavernous space, gasping softly as the afternoon light slants in through a large side window at this long-mothballed Army airfield.

Deathly quiet, the place feels historic. And the 72-year-old Petersen can tell you why.

“This entire base has national significance,” he says proudly. “But this hangar has the most compelling history of all, because it played a vital role in the Manhattan Project.”

During World War II, Wendover’s airfield served as a domestic base for the elite B-17 and B-24 bomber crews. It was also the training site of the 509th Composite Group, the B-29 unit that dropped atomic bombs on Japan to end the war.

The hangar where Petersen stands once served the Enola Gay — the plane known as the first aircraft to unleash an atomic bomb in warfare — and its crew.

At 8:15 a.m. on Aug. 6, 1945, the aircraft dropped on Hiroshima the device code-named “Little Boy,” a 10,000-pound uranium-235 bomb whose explosive force killed or severely injured 140,000 people on the ground below.

For years, the isolated old airfield — set on the parched salt flats of western Utah, 360 miles north of Las Vegas — fell into disrepair, its barracks, hospital, control tower, nurses quarters and hangars all crumbling. In 2009, the building known as the Enola Gay Hangar was added to the National Trust for Historic Preservation’s list of the nation’s most endangered historic places.

When Petersen first visited the hangar in 2000, he saw history in ruins. “Every window was broken, the roof was either totally blown off or patched and leaking,” he said. “The wooden supports were starting to fall away from the structure.”

Then he discovered the old bomb pits, where soldiers used hydraulics to load the 5-ton test bombs into the bellies of the planes before they flew out to decimate mock villages built out on the horizon.

That’s when he had an epiphany.

“Holy smokes, who even knows this is out here?” he told himself. “I’m going to find out all I can about this base. This is such a historic place and it’s literally falling apart.”

Petersen is now executive director of the Historic Wendover Airfield group, an ambitious nonprofit that has raised $2.5 million to begin rebuilding not only the hangar but the airman’s dining hall and the facility’s centerpiece — the 14,000-square-foot former officers’ club that now serves as the base museum.

Williamsburg of the West

For Petersen and others, the Wendover base is more than just a former home of a plane that dropped the atomic bomb. In its heyday, this was the Army Air Force’s largest bombing and gunnery range, its 668 buildings home to 20,000 people — a cross-section of mid-1940s American youth culture during wartime.

The barracks were shared by upstarts from Brooklyn, New York; Bozeman, Montana; and Biloxi, Mississippi — youths who learned firsthand about fraternity, racism and the limits of their own mortality.

Petersen brings a military history to his work. He’s a private pilot and electrical engineer who designed computers for the Air Force in Vietnam before starting a defense contract business in Salt Lake City.

His dream is to create a first-ever Army Air Force museum, what he calls a Williamsburg of the West. “It could be a place where veterans, their families and the American public can walk through and feel like they’ve been transported back in time.”

Thomas Petersen, historian and board member of the Historic Wendover Airfield Foundation, left, and Jim Petersen, foundation president and founder, open the doors of the Enola Gay hangar during a tour of Historic Wendover Airfield in Wendover, Utah. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto

Thomas Petersen, historian and board member of the Historic Wendover Airfield Foundation, left, and Jim Petersen, foundation president and founder, open the doors of the Enola Gay hangar during a tour of Historic Wendover Airfield in Wendover, Utah. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto  William Bishop, whose father, William Ellsworth Bishop, served in the 509th composite group for the Enola Gay, takes in the sight of the Enola Gay hangar while visiting the Historic Wendover Airfieldin Wendover, Utah, on Saturday, May 15, 2021. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto

William Bishop, whose father, William Ellsworth Bishop, served in the 509th composite group for the Enola Gay, takes in the sight of the Enola Gay hangar while visiting the Historic Wendover Airfieldin Wendover, Utah, on Saturday, May 15, 2021. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto But when you excavate any military past, you can dig up controversial memories. Petersen’s nonprofit has grappled with a critical question: Whose stories deserve be memorialized here? Just the bombers, or the people bombed as well?

In 2017, the family of Japanese bombing victim Sadako Sasaki offered to donate one of the legions of origami paper cranes the girl fashioned as a peace gesture before her death from leukemia at age 12.

The offer pressed a hot button: In 1995, officials at Washington’s National Air and Space Museum ignited a protest over plans to include the Enola Gay as part of an exhibition to mark the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II.

Critics called the exhibitors “revisionist social scientists” whose display lacked historical context of the controversial bombing, even the number of casualties. Veterans considered those protests an insult to their sacrifices.

“We wondered how that would look to the families of veterans who came here,” Petersen said. “But on the other hand, shouldn’t we acknowledge all these poor Japanese people who were bombed?”

They decided to display the paper crane in a corner of the burgeoning museum.

“We made the right decision to honor the victims. The horror of nuclear war is a critical part of the story of this base,” said Tom Petersen. “But the veterans who served here had no clue of the impact of what they were training for. This was no shame here. We wanted to respect the servicemen who just did what they were asked.”

Thomas Petersen, second from left in blue, leads a tour of Historic Wendover Airfield in Wendover, Utah. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto

Thomas Petersen, second from left in blue, leads a tour of Historic Wendover Airfield in Wendover, Utah. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto  A tour group passes through a mess hall at the Historic Wendover Airfield in Wendover, Utah. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto

A tour group passes through a mess hall at the Historic Wendover Airfield in Wendover, Utah. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto Reconnecting with past

Several times each year, the Petersens lead an extended tour of the Wendover base as a way to raise money and mark their progress.

On a recent Saturday, the latest group gathered at the airfield museum, browsing displays that include a life-sized replica of the Little Boy atomic bomb.

It was an older crowd, mostly in their 60s and 70s. They’re World War II history buffs, veterans and the grown children of the men and women who once served here.

William Bishop is among them.

The 68-year-old retired banking executive from San Francisco tells how both his parents had served in Wendover, which in the 1940s was so far removed from civilization that the couple felt like they’d been marooned on another planet.

His father, William Ellsworth Bishop, was a backup flight engineer who worked on the Enola Gay and flew on the plane to Tinian Island, where it prepared to drop its infamous bomb. As Bishop recalls, his father was “a farm kid who knew how to work on engines.” His mother, Opal, served in the Army Air Force Nurse corps.

Bishop stared out at the airfield grounds, his eyes glistening with tears, his thoughts in a faraway place. He has come here to reconnect with a personal past.

“Both my parents walked this base. They always talked about the bowling alley, the gym and the mess hall,” he said. “This is the first time I’ve been here. I’m sorry, but I’m a little choked up.”

After he retired, sorting through his parents’ effects, Bishop found a trove of artifacts, inspiring him to visit. One picture shows his mother, sitting atop a rock on base dressed in her nurse’s uniform, waving as the Enola Gay lifted off toward Asia and its destiny. Air Force Brig. Gen. Paul Tibbets, the pilot on the Enola Gay, which he named after his mother, had allowed Bishop to carry a beloved bicycle to Tinian Island.

Nobody knew why they were going or what would happen when they got there. And once they found out, they refused to ever talk about it.

After the war, William Ellsworth Bishop settled back in rural Illinois. He never discussed his mission with his son or the boys down at the American Legion Hall, or even to Smithsonian Museum curators who called the house years later.

Only upon the father’s death was the son allowed to openly discuss the family history, Bishop said. The old man’s funeral included a 21-gun salute. Afterward, a local bar owner bought drinks for the house in honor of Bishop. Only after reading Bishop’s obituary did he realize that he’d had a hero in their midst all these years.

Historical photographs of then-Col. Paul Tibbets and the Enola Gay during a tour of the Historic Wendover Airfield, a World War II-era base. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto

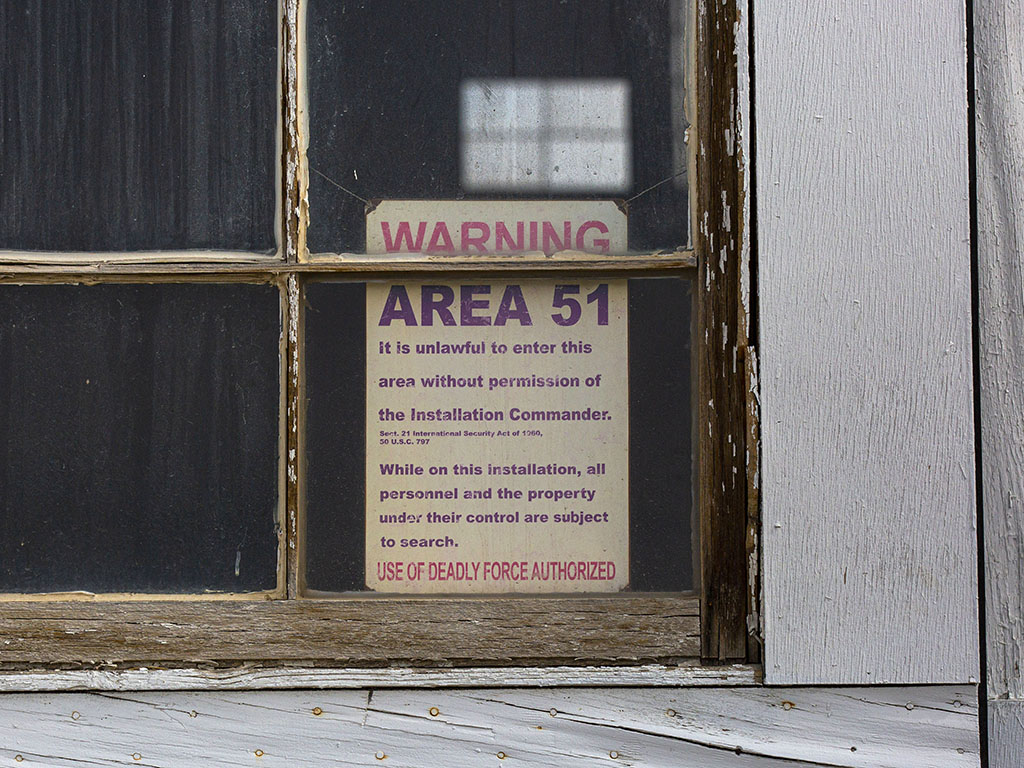

Historical photographs of then-Col. Paul Tibbets and the Enola Gay during a tour of the Historic Wendover Airfield, a World War II-era base. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto  An Area 51 warning sign is seen during a tour of the Historic Wendover Airfield, a World War II-era base in Wendover, Utah. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto

An Area 51 warning sign is seen during a tour of the Historic Wendover Airfield, a World War II-era base in Wendover, Utah. (Chase Stevens/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @csstevensphoto Tiny paper crane

Jim Petersen also faces this code of silence, which he says was reinforced by a sign Tibbets kept in his office that read, “What you see here, what you hear here, when you leave here, let it stay here.”

One veteran refused to discuss his role in Wendover, even after Petersen had assured him that all the work had been declassified. “I’m sorry, I just can’t,” he insisted. “I’ll get in trouble.”

While Sadako Sasaki’s paper crane is not included on the official tour, it was on the minds of many in the group. As he toured the airfield, Bishop said he had no problem with the artifact being displayed at the museum.

“My father always believed that he helped stop the war,” he said. “But there’s another side and we need to know that history. Good or bad, we need to know.”

Not everyone feels that way.

Tour member Bill Echols said his father, Marvin, was a B-29 pilot who was serving in Alaska when the bomb was dropped on Hiroshima.

“All aspects of the war ought to be remembered,” he said of the crane. “Obviously, Japan has its own part of the story. I guess I’m more interested in our side than theirs.”

Just around the corner, volunteer airfield guide Frank Conte peers into a small display case at Sasaki’s tiny paper crane, which is the size of an almond. “Whether people agree or disagree about the crane being here, a lot of people just don’t want to see the human side of the dropping of that bomb.”

He pauses. “And this is the human side.”

Edwin Hawkins knew the hard emotions the crane would evoke.

The Japanese-born retired U.S. Air Force colonel was part of a contingent, along with a Sasaki family member, who attended the crane’s 2017 unveiling in Wendover.

He knows about the competing narratives of justification and victimhood and believes both should be told.

That day, Hawkins gave an emotional speech he hoped would make sense to all.

The event, he said, was not to criticize “the crew of the Enola Gay … but recognize their service and heroism. At the same time, we remember the tragic victims of their act, the dropping of an atomic bomb, symbolized here by Sadako’s paper crane.”

He added: “We can and should do both. Because by understanding these respective truths, we will be able to move forward.”

Four years later, Hawkins is still moved by the events of that day. “There was no enmity, no recrimination,” he says. “Just a desire to reach out.”

All about life

Still, Jim Petersen’s tour at the Wendover airfield is all about life, not death.

Soon after he first visited the airfield in 2000, Petersen’s interest morphed into a crusade. In 2005, he became airfield manager, a job he held until his retirement in 2016.

But the work continues at the old airfield, closed by the Army in 1963 — the historical research, grant applications, funding drives and so many two-hour trips from Salt Lake City that his wife, Kathi, might be called “the Widow of Wendover.”

Petersen would like to get an original B-29 to display full time here, in memory of the real war birds that once flew the skies overhead. For now, he makes do with the Fairchild C-123K, the plane featured in the 1977 movie “Con Air,” which was filmed here.

Between father and son, these four-hour airfield tours feature a decided personal touch. Jim Petersen describes the secrecy and separation of duty that pervaded life here as military ordnance arrived daily: “The manufacturers didn’t know where the parts were going and the men unloading them here didn’t know where they came from.”

As the tour group circles an old bomb loading pit, Petersen describes how 400 undercover FBI agents kept an eye on base doings, assigned as latrine orderlies, typists and cooks, “all on the lookout for loose lips.”

Men were tailed when they went on leave. Their calls and mail were monitored. But the boys on base waged their own subterfuge. They found there was one shipment that even the FBI goons couldn’t inspect — so that’s where they hid their illicit booze.

After so many tours, Tom Petersen still recalls the widow of a serviceman once stationed here. English-born, in her 90s, she leaned on her daughter’s arm as she walked into the mess hall.

“She began to weep, saying, ‘You can feel them in here, can’t you?’ ” he recalled. “That’s when I thought to myself, ‘Man, we did something right.’ ”

John M. Glionna is a former Los Angeles Times staff writer. He may be reached at john.glionna@gmail.com.