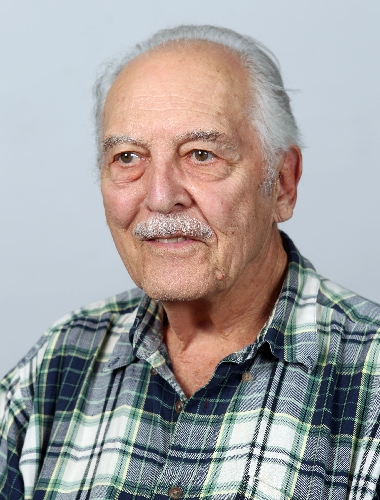

Valley veteran remembers death camp atrocities of WWII

Just before New Year’s Day 1945, Don Worpell packed his gear for a train ride from Camp Butner, N.C., to what his World War II papers described as a "secret destination" in Massachusetts.

His crack artillery unit had spent six months in Carolina’s hardwood forest honing their long-range gunnery skills, and Worpell, a 21-year-old draftee from Detroit, had just completed eight months of engineering courses at Loyola University on the Army’s dime.

Instead of the .30-caliber carbine that he slung over his shoulder, he was ready to fight the war with maps, a range-finder and a surveyor’s transit. He would use these tools and his math skills to calculate where his team should aim their howitzers to kill the enemy.

It was all part of a plan to help Lt. Gen. George S. Patton drive Nazi forces on a breakneck retreat after the Battle of the Bulge.

He had no idea when he left the "secret destination" staging area at Camp Myles Standish and boarded the troop ship at Boston Harbor on Jan. 10, 1945, that he was beginning a journey that would change his life forever.

"It took us two weeks to get across because we were zigzagging to avoid German submarines. That was a long time on the ship," he said of the vessel, Uruguay, which dropped anchor at Le Havre, France, on Jan. 21, 1945.

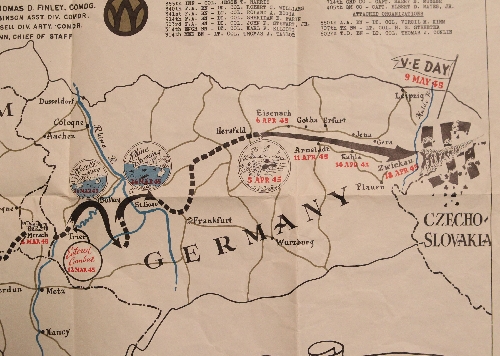

After a few months of firing their big guns to chase Nazi troops, Worpell and the rest of the 914th Field Artillery Battalion witnessed the horrors that soldiers in Patton’s Third Army found when they liberated Ohrdruf concentration camp in early April 1945.

The soldiers of the 914th stood behind Patton, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower and Gen. Omar Bradley when they saw where American POWs too weak to walk as human shields had been gunned down by Nazi guards at Ohrdruf. It was, Worpell said, days before Adolf Hitler committed suicide.

"I was just in awe of all the death and mangled bodies," recalled Worpell, 89. "As we got close to Ohrdruf, the guards shot all the prisoners who could not travel."

The reflections of Worpell, former psychologist at the Las Vegas Mental Health Center, are backed up in the battalion’s log from April 6, 1945.

"It was here that the first real Nazi ‘horror’ atrocities were viewed by the members of the 914th. The concentration camp of Ohrdruf was a revelation to be indelibly etched in the memories of all men of the 914th Field Artillery," the narrative reads.

"Men lying in heaps where they had fallen when murdered was one sight; a neat stack of at least 50 murdered bodies sprinkled thoughtfully with lime; and a large improvised incinerator which disposed of countless numbers of unfortunate prisoners."

The sight, said Worpell, even upset Patton, the "blood-and-guts" general known for his toughness: "Patton started to cry. Eisenhower just stood there looking."

Worpell’s battalion, part of the 89th Infantry Division, had bombarded the Germans on their retreat, driving them across the Rhine River in late March 1945. Some days they fired hundreds of 105 mm shells.

"I rode on a truck, and my job was to calculate where our howitzers should shoot to get the Germans," he said.

"I’d have to go out into the field and survey their positions," he said of the artillery squads. "They’d get information from the forward observers, and using algebra and trigonometry, I’d figure out how they should aim their guns to hit the targets."

The German soldiers, he said, "kept running in front of us. They were being chased. As they left, they were killing people along the way because we found bodies in the ditches and along side the road."

The war left its mark on all the soldiers of the 914th, according the unit’s narrative, which described the battalion’s return to the French coast in June 1945.

"Taps was sounded for the battalion in France, a battalion which had just reached the peak of fighting efficiency in combat as the war ended," the log reads. "However, a new era of peace faced all these men with a challenge for the future – the future which was fought for."

Worpell completed his tour unscathed, but his brother, who also served in Europe, was wounded.

Looking back, he said the experience "was a terrible situation, but it was something we had to do. The world came out better because of what we accomplished. Hitler was out to conquer as much as he could. So we put a stop to him."

Nevertheless, he said, "It cost us a lot of money, a lot of lives, and there was a lot of limitations in this country because of that."

Worpell continued his college education on the G.I. Bill after coming home, but switched majors, earning a doctorate in counseling, guidance and psychology from the University of Michigan.

He then spent 25 years helping people at the Las Vegas Mental Health Center.

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.