Remembering Nevada’s ‘Wild West’ division in World War I

The stories of the Calac cousins and other Nevadans who fought in World War I echo very faintly today.

Only shorthand accounts of their heroism, sacrifice and accomplishments are etched in stone or handed down in family stories from generation to generation.

But approaching the 100th anniversary of the U.S. entry into the “war to end all wars,” the improbable tale of the Calacs and the Army’s 91st “Wild West” Division — a ragtag legion of shopkeepers, cowboys, farmers, miners, Native Americans and immigrant railroad workers who helped change the course of history — demands one more telling.

“The 91st was a group of young, inexperienced kids from the West who became valiant soldiers in this new army,” said Bryan Woodcock, a retired Army helicopter pilot and historian who wrote his military college thesis on the 91st. “With the spirit of true cowboys, as many of them were, these frontiersmen were repeatedly bucked off and kicked in the face. Yet they always stood back up, dusted themselves off and continued to ride forward.”

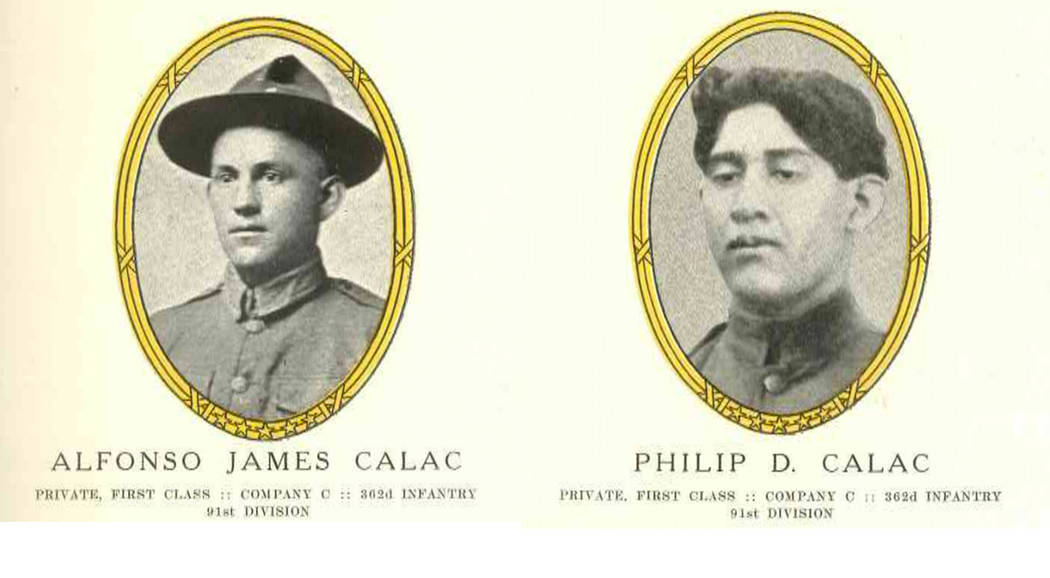

The Calacs, Alfonso and Philip, were Native Americans who in some ways typified the roughly 20,000 soldiers of the 91st Division dispatched to France in the summer of 1918.

Members of the Rincon Band of Mission Indians near San Diego, they had no intention of joining the Army when they left the reservation to work for the railroad in Las Vegas. It was 1917, and the war in Europe seemed worlds away from the town of about 2,000 residents with no paved streets.

Alfonso Calac, 26, was an “educated and trustworthy blacksmith helper” for the Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad Co., military records say.

Philip Calac, a tall, 21-year-old with dark brown eyes and thick black hair, was a boilermaker’s helper at the railroad shop in Las Vegas.

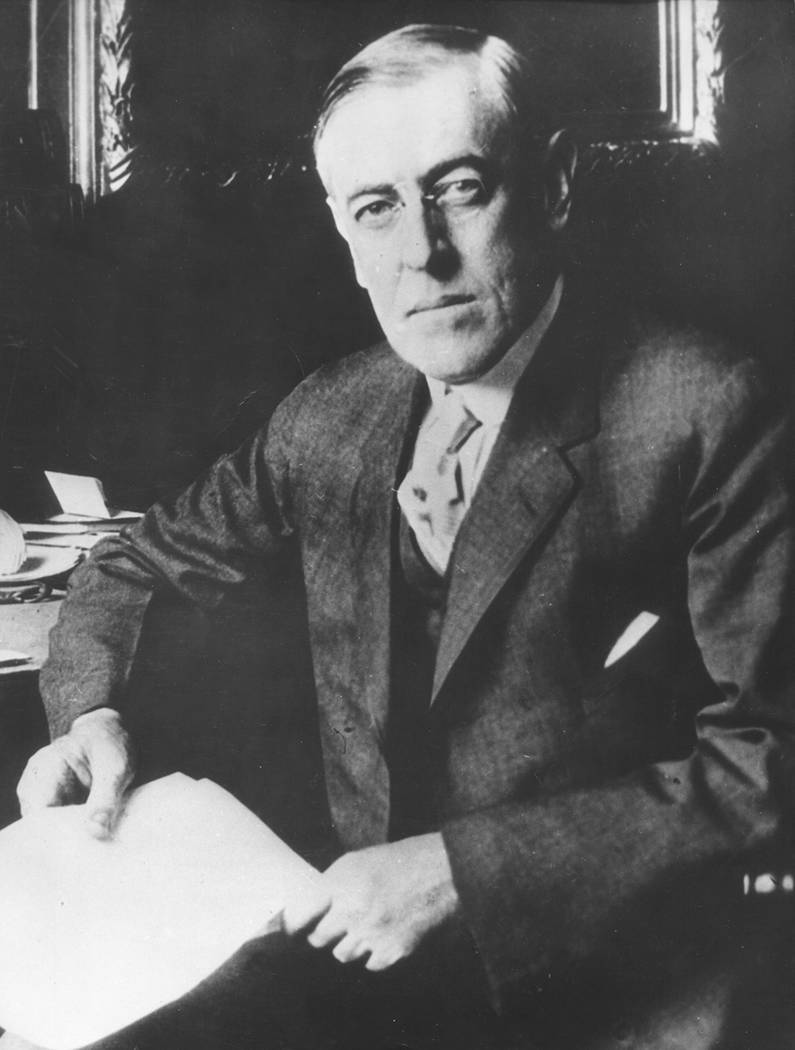

The cousins were among the 4.8 million young men whose lives were upended when President Woodrow Wilson, who had campaigned on a pledge to keep the U.S. out of the war, reversed course and asked Congress to declare war on Germany on April 2, 1917. His reason: The empire’s submarines were sinking U.S. ships, and Germany was attempting to strike an alliance with Mexico in return for help “reconquering” Texas, New Mexico and Arizona. Congress complied four days later.

HEEDING UNCLE SAM

When they registered for the draft in Las Vegas on June 5, 1917 — initially required of all able-bodied men in their 20s – the Calacs likely did so beneath a poster of finger-pointing Uncle Sam saying “I Want You,” an iconic call to arms in wide circulation at the time.

They may have had a powerful inducement to enlist: the promise of U.S. citizenship.

William Bauer, a UNLV expert on Native American affairs, said many American Indians “volunteered for the Army during World War I because they were not United States citizens” and were guaranteed citizenship if they enlisted. (Congress didn’t guarantee citizenship to all Native Americans until 1924.)

Because citizenship was granted to individuals and some tribes and also could be obtained through marriage and other means, it’s not clear whether the Calacs volunteered or were drafted.

That’s also true of everyone else on Nevada’s draft registration list from the time, including Shoshone Joe Jackson, a Native American farmer from Belmont, now a Nye County ghost town, who wrote that he didn’t know the month or day he was born, though it was in the spring of 1888.

Patriotism did fuel many signups.

Among them were Gus Pappas and his brother, John, both of whom had emigrated from Greece as boys. John came first, arriving in Las Vegas in 1902 and finding work delivering water to rail line workers. Gus followed and ended up in Ogden, Utah, where the brothers met up and decided to join the Army.

“They wanted to fight for America even though they were basically Greek,” said Harry Pappas, 63, John’s son and a longtime Las Vegas resident. “They were both patriotic. They were both rah rah, America.’”

Other recent immigrants heeded the call for reasons that are lost to history, including German-Americans and a Japan-born railroad laborer from Caliente in Lincoln County named Itakka Takahara.

The draft list also included miners and hotel clerks and cowboys – in high demand because of their ability to train and ride horses still widely used to haul supplies and artillery — from places like Virginia City, Carson, Reno and Elko.

Horace Greely Bliss, a farmer from White Pine County in east-central Nevada, became a machine gunner and was shot and killed by a sniper in France a month before the war ended.

Others like Navy Seaman 1st Class William K. Lamb, son of former sheriff Selah Lamb of Winnemucca, never even made it overseas. He died of influenza at Mare Island, California, about the same time as Bliss.

All told, Nevada mustered nearly 1,500 men out of a total state population of about 81,000. Most were drafted, but patriotism helped make Nevada No. 1 in the nation in terms of per capita volunteers.

OVER HERE

Most of Nevada’s newly minted soldiers reported for training with the 91st “Wild West” Division at Camp Lewis, near Tacoma, Washington. The division was composed mostly of draftees and drew its nickname from the frontiersmen from the Northwest, the Mountain States, the Southwest and the territory of Alaska that filled its ranks.

The assembled horsemanship came in handy, as “rodeos were staged throughout their time at Camp Lewis,” said Woodcock, himself a veteran of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who was drawn to study the 91st because a great uncle from Wyoming had fought – and died – with the division.

“It was said there was never a rodeo that could find world-class sportsmen better than at the 91st, because they had the cream of the crop.”

John Pappas was rejected when he tried to enlist. “He was either overweight or had flat feet,” said Harry.

Brother Gus, however, made the cut and was soon bound for France.

In the summer of 1918, after an abbreviated training that consisted of lots of basic drilling and not much marksmanship, the 91st traveled east to New York to board ships to Europe.

OVER THERE

Upon arrival in France, the men of the 91st — many of whom had never been outside their home states, or counties in some cases — found themselves in a strange land and in the midst of a new kind of military conflict.

World War I was fought with horses and cannons and bolt-action Springfield rifles, weapons that many Westerners were relatively familiar with. But new tools of war, such as rhomboid tanks, machine-gun-mounted biplanes and zeppelins and observation balloons, were making battlefields much deadlier.

The soldiers soon discovered that war could be unpredictably dangerous when a French freight train slammed into a stationary train carrying men from the 91st on July 25, 1918, near the town of Bonnieres, killing 32 and badly injuring scores more.

After another abbreviated training period near Paris, the division was moved to the Western Front. It was kept in reserve at the Battle of Saint-Mihiel and saw no action.

That changed dramatically when the 91st was picked to “carry the ball” in the Meuse-Argonne offensive by pushing through the center of heavily entrenched German lines extending from the Argonne Forest to the west to the Meuse River in the east.

Thousands of soldiers of the 91st marched to the front on successive nights and hid in a forest just behind the front lines to try to keep the coming attack secret from the German forces entrenched within shouting distance.

Soldiers and Marines wore steel-rimmed “doughboy” helmets and gas masks, sometimes sleeping with them on to guard against chemical warfare agents like blistering mustard gas and deadly phosgene and chlorine launched by German artillery.

“Gas alarms were popular during the night. … This forced some men to try and sleep in their masks, but they found it very uncomfortable. The rain fell in torrents at times … until it made the muddy ground and woods almost unbearable,” according to a “History of the 362nd Infantry” published in 1920.

‘OVER THE TOP’

When called upon to “go over the top” of their front-line trenches on Sept. 26, 1918, the soldiers of 91st made up for their inexperience with ferocity and tenacity.

The Calac cousins and many other Nevadans served in the division’s 362nd Infantry Regiment, which led the northward advance that was later compared to “The Charge of the Light Brigade.”

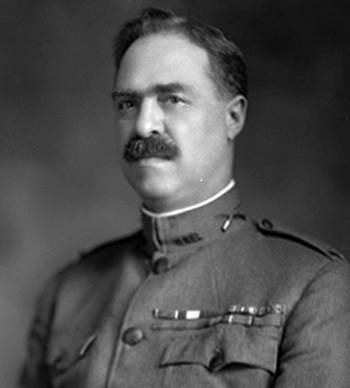

The unit, led by Col. John Henry “Gatling Gun” Parker, braved heavy shelling and machine gun fire, losing hundreds of comrades but managing to punch through the Germans’ third line of defense and seize their objective, the French village of Gesnes, on the fourth day of fighting.

So rapid was the advance that the U.S. troops fighting on the flanks of the 91st were left behind, leaving the division dangerously exposed. That led U.S. commanders to order the exhausted soldiers to retreat over the terrain they had just captured.

“No one can describe the feelings of the men when they received the order and realized what it meant: that the ground which they had taken at such terrible cost was to be given (up) and that the blood of their comrades had been shed in vain,” recalled T. Ben Meldrum, author of the “History of the 362nd Infantry Regiment.”

Gus Pappas also fought with distinction, but he got into trouble when he was escorting about a half-dozen captured German soldiers to the rear.

“He saw one of them pulling out a little Luger (pistol) … and he shot them all dead. And because he shot them all, they took him and threw him in the brig,” Harry Pappas said of his late uncle.

Within a couple weeks, though, with attrition of U.S. troops, “they let him out of jail and put him back on the front,” Pappas said.

The incident didn’t stain his uncle’s reputation as a war hero, which he parlayed into an acting career in Hollywood after the war, he said.

SKETCHY DETAILS OF DEATHS

The Calac cousins were not so fortunate.

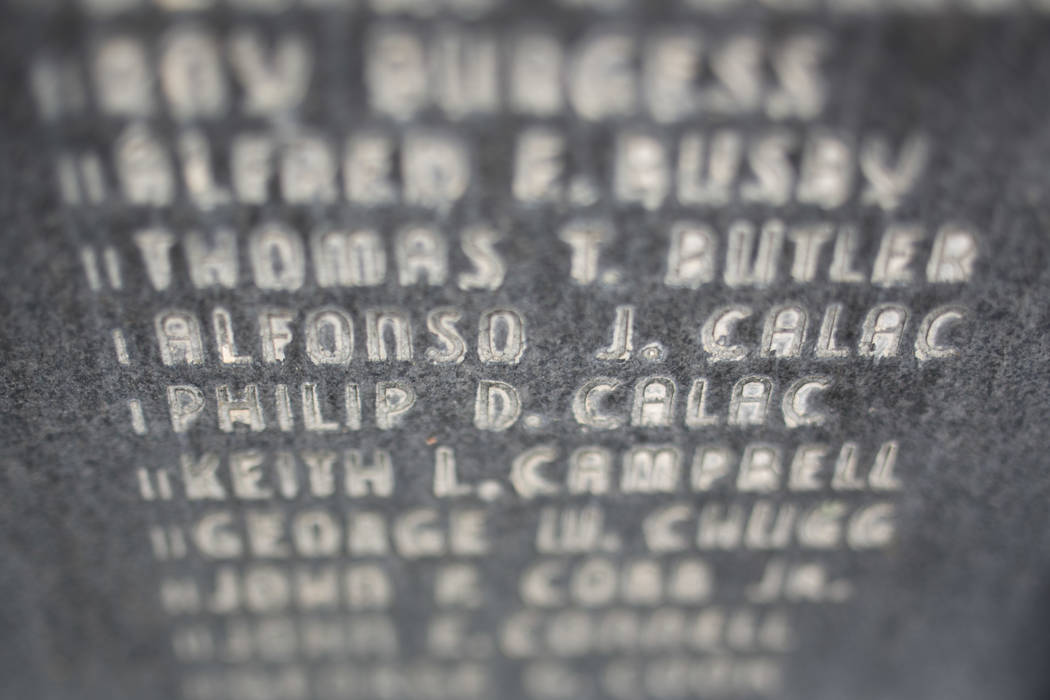

An unobtrusive granite-and-concrete monument near the corner of Las Vegas Boulevard and Bonanza Road bears silent witness to their ultimate sacrifice. Erected in 1952, the Gold Star Mothers memorial simply lists their names and those of many other Southern Nevadans who lost their lives in the war and other U.S. military actions.

Only the barest details of Philip Calac’s death were recorded by the 362nd Infantry Regiment Association:

During the battle for Gesnes, corporals were bandaging Calac “who appeared to be seriously wounded. While trying to administer first aid to Pvt. Calac, (when a) shell fell near the group, killing Pvt. Griffin. Both Cpls. Dawson and Olson are of the opinion that Pvt. Calac was killed at the same time, 4:10 p. m. Sept. 29, 1918.” He is buried in Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery in France.

Pvt. Alfonso Calac died of unspecified wounds the same day. His grave is atop a hill southeast of Gesnes.

The Calacs were among 194 soldiers, sailors and Marines from Nevada who died in the war, 47 of them killed in action, according to Air Force Tech. Sgt. Emerson Marcus, the Nevada National Guard’s historian. The rest perished in accidents or succumbed to disease or battle wounds.

One of the oldest living members of the Calac family, DeLisle Calac, 88, of Escondido, California, said he wasn’t born until 10 years after the armistice and only vaguely remembers his family talking about an aunt who lost two family members in France.

Though Calac is only now learning more about his relatives’ sacrifice, he is pleased that the centennial of the U.S. entry into the “war to end all wars” has renewed interest in their story, said Nikki Symington, spokeswoman for the Rincon Band of Luiseño Indians.

“Who knows that 14,000 American Indians volunteered for World War I, before we were even granted American citizenship?” she quoted him as saying.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2

NEVADA’S WORLD WAR I DEATHS

According to the Nevada Department of Veteran Services, the following military members from the state died as a result of their military service either in combat overseas, or from disease or accidents, including those who died in the United States or in transit.

Leonard Charles Aitken

Eliot V. Ames

Clarence J. Anderson

Arlo C. Armstrong

Joshua M. Battin

Maurice Bair

Elmer Jefferson Bell

John Benevent

John Campbell Bett

Charles Ellis Beuhanon

Horace Greely Bliss Add a Hero

Carmelo Bloisi

Clinton Lodi Bonser

Kenneth James Booth

Frank Howard Brenton

Gus Bouzas

Lawrence Broe

Thomas Ross Brooks

Daniel Eldred Bruce

Everett Nathaniel Buck

Frederick Bullers

Roscoe Carlyle Bulmer

Harris Lloyd Butler

Alfonso James Calac

Philip D. Calac

Archie Sutherland Campbell

Alvin P. Carlsen

Marvin H. Carpenter

Robert Ford Carter

Louis M. Ceresola

Karl W. Chartz

Thomas M. Claudio

Patrick Hugh Clancy

Michele Colucci

Henry Cooper

John C. Cooper

Vernon Crossen

Georg Bun Culp

Georg Samuel Dailey

Amie Frank Davin

George Stevens Davis

Lute Davis

Charles August Davison

John Francis Doherty

Darrell M. Dunkle

Milo N. Dumovich

Peter O. Durenberger

Thomas Henry Edsall

William Ellithorpe

Knud L. Eriksen

Marion J. Ewing

Philip J. Fessenden

John Wesly Fitchue

William J. Flynn

Lawrence P. Foged

Reuben Fowler

Antonio Lucio Freitas

Clarence H. Frevert

Frank S. Fuller

Onorato Gadda

Walter J. Gallagher

Peter Galli

Joseph P. Garcia

Augustino Gatti

Sammy George

Charles Gifford

Herman G. Glasmeier

William T. Gleason

Marvin B. Grey

Leander R. Grubbs

Henry J. Gosse

Frank J. Hagen, Jr.

James Hall

Arthur F. Hampton

Jesse K. Harling

Charles W. Heflin

Robert F. Hildebrand

Charles F. Hobbins

William J. Horgan

James Horton

Alexander Hunsucker

Clarence Huntsman

William J. Hurt

John W. Jackson, Jr.

Lester H. Jacobs

Earl F. Jepson

James A. Jewell

Harry Johnson

John Joseph Jones

Barney T. Justesen

George L. Jordan

Charles Kahlmeier

Austin R. Kernek

Yaro Klepel

Vido Kuliacha

William K. Lamb

Edward J. Landrigan

Norman C. Leonard

Frank H. Lathrap, Jr.

Alexander F. Leslie

Chester A. Lillie

Alfred P. Liston

Ole A. Littleton

James E. Lowe

Fred Lundgren

Frank M. Madalena

William Magarrell

Philip A. Malo

Battesta Mancassola

Bill Margeas

Henry F. Marsh

Harold Martin

Alfred H. Matthiessen

George McCain

William J. McCabe

George L. McCall

Harold C. McCarthy

Charles D. McNamee

Robert D. Merney

Eugene V. Merrigan

Sidney J. Migues

Krsto Mijuskovich

Myles M. Miller

Ernest J. Minoletti

Corbet Mitchell

Cornelius Molenbeck

George E. Mollart

Frederick P. Moore

William J. Morrison

John E. Newman

Edward G. North

Robert A. Newell

Thomas V. O’Hara

Charles F. Oldham

Frank E. Olsen

Orville J. Olson

Samuel H. Opdal

Harry Pappas

Frank Patocka

Oliver M. Peacock

Woodruff Perkins

Frank Peters

Johannes Persson

Peter H. Petersen

Winfred Pike

Ernest A. Plack

William Quesnell

Richard B. Ramsey

Lloyd Ramsey

Chester F. Reid

Lauren G. Reid

James P. Restos

Gino Roberti

Thomas E. Roberts

Howard V. Robins

George V. Rose

Clarence Rosenbrock

John T. Sayer

Louis G. Scanavino

Fred W. Scott

John F. Shain

Guy M. Shepherd

Alexander Silva

Adolfo Siri

James Siri

Roxy W. Slater

Edward R. Smith

Joseph F. Smith

Ray M. Smyth

Ferney G. Snare

Wilbourne Stock

Ernest J. Stover

Walter G. Swedberg

Melville O. Talley

Neil E. Taylor

William Taylor

Antonio P. Teixeira

Antonio F. Tenente

Domenico Tagniotti

Ernest Twaddle

John Valdez

Arist D. Vallas

Gereene Van Burger

August Viaene

Adolph Vollmar

Harry Vollmar

Clive A. Walker

Joseph S. Webb

Frederick W. Whitburn

Luther J. Wilson

Paul K. Wilson

Walter H. Wise

William P. Wuyovich

Henry J. Yelland

Birchard G. Yocum

NEVADA WAR DEAD BY ERA

Civil War — 31

World War I — 194

World War II — 426

Korean War — 46

Vietnam War — 148

Iraq/Afghanistan — 79*

Source: Nevada Department of Veterans Services

*Includes overseas military deaths since Sept. 11, 2001 with strong ties to Nevada.

U.S. RELUCTANTLY GOES TO WAR

— The “Great War” in Europe had been underway for nearly three years when President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany on April 2, 1917, saying “the world must be made safe for democracy.”

— War erupted July 28, 1914, when Austria-Hungary forces invaded Serbia a month after Austrian Archiduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife were assassinated in Sarajevo by Yugoslav nationalist Gavrilo Princip.

— Germany sided with Austria-Hungary and invaded Belgium, Luxembourg and then France. Great Britain entered the fray to defend Belgium, as promised 75 years prior under the Treaty of London.

— The United States remained neutral despite a torpedo attack by a German U-boat on the British oceanliner RMS Lusitania, which killed more than 120 Americans on May 7, 1915, and the sinking of the American steamer Housatonic by a German sub nearly two years later.

Public opinion shifted after Wilson released the so-called Zimmermann telegram on Feb. 28, 1917. The message from Germany’s Foreign Minister Arthur Zimmermann, intercepted and decoded by British intelligence, directed the German ambassador in Mexico City to propose an alliance between Germany and Mexico in the event the U.S. entered the war in exchange for Germany’s help “to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico and Arizona.”

— After Germany sank four more U.S. merchant ships over the next month, Wilson asked Congress to declare war on the German Empire.

“It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance,” Wilson told Congress on April 2, 1917.

— Four days later Congress declared war, by votes of 82-6 in the Senate and 373-50 in the House.

— The first woman in Congress, Rep. Jeannette Rankin, R-Montana, voted ‘no,’ saying, “I want to stand by my country, but I cannot vote for war.”

VOICES OF THE 362ND INFANTRY REGIMENT

“As the men fell back in the darkness, they gathered up most of the wounded. The night was black and cold and rain that was half sleet fell. … The moaning cries of the wounded seemed to come from everywhere out of the darkness. Here and there a man was found wandering about among the dead and wounded like a lost child; rendered so by the terrible shock and horror of the carnage,” — about the battle for Gesnes published in the 1920s by 362nd Infantry Regiment Association.

“We have taken Gesnes and the ridge beyond, have dug in, have food and water, and can and will hold until Hell freezes over.” — message from the regimental adjutant to Col. “Gatling Gun” Parker.

“Company F and other companies of the 362nd Infantry were lying on an open field. The orders were to go over the hill and take a town straight in front on the other side. We started up the hill and had just reached the brow of it when Charles Kahlmeier was killed. I think it was a machine gun bullet that struck him. He fell back, held himself up on his hands a few seconds then sank dead,” — Cpl. Wicliffe Olsen, Miles City, Montana.

“Your son gave his life toward one of the most imporant achievements of the war. The Argonne drive was one of the big factors in bringing about the total defeat of Germany,” report of Kahlmeir’s death, Feb. 17, 1919 Arizona Republic

THE 91St IN WORLD WAR I, AT A GLANCE

Troop strength: Nearly 20,000 at the outset, including about 1,000 from Nevada. The men are drawn from California, Washington, Oregon, Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Montana and Wyoming and the Territory of Alaska.

Casualties: 6,108 (1,134 killed and 4,974 wounded in action)

Mottos: Powder River!, Let ‘er buck! and Always ready!

According to an Army history of the 91st, the unofficial motto was coined by a young cowboy from Wyoming who was asked where he was from. The response from the lad, clad in riding chaps and a cowboy hat, “From Wyoming, sir! Powder River! Let ‘er Buck!” “Always Ready” was the official motto, selected when the division created its distinctive fir tree patch in late 1918 in Belgium.

Patch: The 91st didn’t have a patch until the end of the war, when the fir tree was picked. “They chose that because it was common to all of the states that the soldiers of the 91st came from,” said military historian Bryan Woodcock. The evergreen also was seen as symbolic of the division’s official motto: Always ready!