Las Vegas veteran, 87, recalls POW days at Nellis ceremony

Ray Hamman doesn’t consider himself a war hero. Instead he is “a survivor.”

The heroes, he said, are the roughly 417,000 U.S. military personnel who gave their lives in World War II. The list of those killed in action includes many from his 483rd Bomb Group. In a single day in 1944 the group lost 140 men when 14 bombers went down.

While he wasn’t in one of those ill-fated planes, Hamman was one of the thousands of U.S. soldiers and airmen who walked away from Germany’s large st prisoner-of-war camp — Moosburg Stalag 7A — after tanks from Gen. George S. Patton’s 14th Armored Division blasted their way through the last pockets of Nazi resistance.

Hamman, 87, still has the boots he wore through the ordeal, from March 13, 1945, when the B-17 bomber he was in crash-landed in Yugoslavia to the day the Moosburg camp was liberated, April 29, 1945.

“I was just so happy that tank came through. I knew that instant we were going to be free,” he said in an interview this week before attending Friday’s POW-MIA Recognition Day ceremony at Freedom Park on Nellis Air Force Base.

“God took care of me,” said Hamman, who has lived in Las Vegas since 1955 with his wife, Barbara.

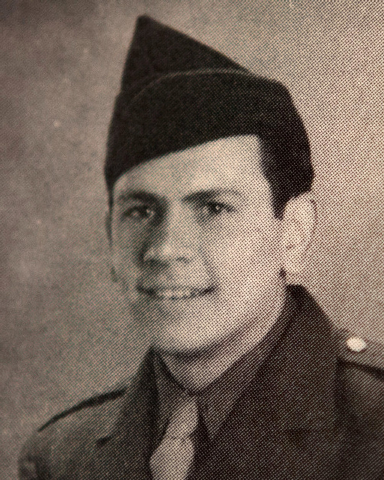

His odyssey began in 1943 when he joined the Army Air Corps after graduating from St. Louis’ Southwest High School. A year later, as a 19-year-old ball-turret gunner, he was flying on bombing runs out of Italy with the 15th Air Force.

“I was there through the winter and flew 15 safe missions. On the 16th mission two of the engines faltered and the pilots tried to return to the base,” he said, recalling when the Flying Fortress veered from the formation as it lost speed high over Austria.

When the B-17 descended into Yugoslavian airspace it was hit with anti-aircraft fire that put several holes in the plane and knocked out a third engine, leaving only one with full power.

“We dropped the ball turret in flight and threw all the ammunition out, everything to lighten the plane but it still crash-landed near a town called Ljubljana,” he said.

“We all rushed out of the plane. You could smell oil, gasoline and oxygen. The first thing we did was congratulate the pilots because we were safe and there was no fire.”

The crew, however, was immediately captured.

“It was very easy for them,” he said. “The Germans were tracking our position. They had a motorcycle with a sidecar and a machine gun mounted on it. The driver got off and told us, ‘put your hands up.’”

The crew complied but Hamman said there was some relief in the back of their minds. “We all agreed the war is going to be over pretty soon.”

But would they live to see the end of it?

The Nazi motorcycle sergeant marched them in the early afternoon to a barn about a mile away. Then about 8 p.m. a German truck arrived and hauled them to Ljubljana, where they stayed for six days until some Luftwaffe guards showed up to escort them on a freight train over the Alps.

“It was real pretty and sunny. We were hanging on. Nobody was in danger but it wasn’t like you’re sitting in a passenger seat,” he said. “You could have escaped if you wanted to but I didn’t want to escape in the mountains with freezing temperatures at night. You’re chances of surviving out there were worse.

“You feel good by having companions. You’ve got 10 guys. We’re all together and nobody is hurt or injured with broken bones. It means a lot.”

About this time, on March 25, 1945, his mother, Lydia Hamman, received a Western Union telegram bearing grim news at his St. Louis home.

“The Secretary of War desires me to express his deep regret that your son, Sgt. Hamman, Raymond R., has been missing in action over Austria since 13 MAR 45,” reads the faded, beige telegram signed by The Adjutant General J.A. Ulio.

Meanwhile, Hamman’s POW journey continued. They arrived in Munich, took some street car rides punctuated by transfers around bomb craters and finally got on a train destined for Nuremberg.

“The allies were advancing and they bombed Nuremberg. We were only three miles from town and we heard all the bombs but they didn’t hurt any of us,” Hamman said.

Then, on April 4, 1945, the U.S. colonel in charge of the prisoners huddled with German officers to discuss marching some 12,000 POWs through Bavaria.

“We were all in a long line. It might have been six, eight or 10 miles long. We just walked on different roads through the Bavarian countryside.”

When Hamman’s crew finally reached Moosburg, he was put in a tent with 500 POWs. “You had a piece of land about 2 feet by 6 feet. That was your possession. That’s where you lived.”

Food was scarce but parcels from the Red Cross kept them alive. One small box shared by two POWs had “American things, even cigarettes,” he said. “A little cheese, a little chocolate. All small stuff but highly nutritious. With water it amplified. You seemed pretty full with just a little bit of food because with water it got bigger in your stomach.”

Despite the Red Cross parcels, Hamman lost 18 pounds during the seven weeks he was held captive.

When Patton’s tanks arrived the prison guards came out of their barracks and stood in two rows. “They put their guns, rifles or pistols out in front of them at their feet and they just stood there.”

On May 14, 1945, a Western Union telegram announced the good news to his parents that he had been “returned to military control.” It came with this message in all capital letters: “ALL WELL AND SAFE. HOPE TO SEE YOU SOON. ALL MY LOVE. RAYMOND R. HAMMAN.”

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.