Las Vegas psychiatrist helps Vietnam veterans heal ‘invisible wounds’

Until he began therapy sessions with Dr. Steven Kingsbury to cope with post-traumatic stress disorder, Marine veteran Lonnie Coslow was in denial about his invisible wounds from the Vietnam War.

“I told him that if the Marines wanted me to have PTSD they would have issued it to me,” Coslow, 71, said Thursday.

Looking back, Coslow now understands how Kingsbury, a wheelchair-bound psychiatrist at the North Las Vegas Veterans Affairs Medical Center, helped him realize how to live with the nightmares, flashbacks and pent-up emotions that have simmered since 1968.

Kingsbury became a mental health expert after earning degrees, completing residencies and serving on faculties at universities like Harvard, Loyola, Miami, Texas and Southern California. Through his knowledge and experience he gradually won Coslow’s confidence.

After 10 years of private sessions with Coslow, the affable doctor persuaded him to join the Tuesday gatherings of a group of about 20 other Las Vegas area combat veterans.

“One of the great things we had going was we saw these guys in a group and they were able to help each other,” Kingsbury said. “Any trust issues that they had with me, they still had trust among themselves.”

When issues like suicidal thoughts, marriage problems and anger flare-ups surfaced, he said, “They were there for each other and they could call each other and just get away for awhile.”

Since Kingsbury retired two years ago, the veterans have stayed in touch with him. But with his ability to get around diminished by multiple sclerosis, a disabling disease of the central nervous system, they urged him to share some of his insights for working with PTSD patients in an interview with the Review-Journal.

He said when it comes to coping with PTSD, “everybody is different but the common denominators are safety and control.”

“I’m not sure I taught them that. I helped them realize that,” said Kingsbury, 68.

He added that anti-depressant medications can augment therapy, but he prefers that veterans work through their issues without them.

“Medications are often part of a safety net,” he said. “There is no medication that is going to cure PTSD.”

HELP FINDING SOLUTIONS

Coslow’s mental scars run deep. A machine gunner along the demilitarized zone, his mobile weapons platoon, Kilo Company, was a constant target for rocket and artillery fire from the North Vietnamese Army.

“We lost almost all of the company in the Battle of Valentine’s Ridge,” he said about the encounter Feb. 14-15, 1968, near their Ca Lu fire base.

For years, even decades, after the war ended, many combat veterans refrained from socializing because they were worried that people outside their small circle of family and friends wouldn’t understand what led to their myriad of symptoms, from short tempers to angry outbursts, survivor’s guilt and depression.

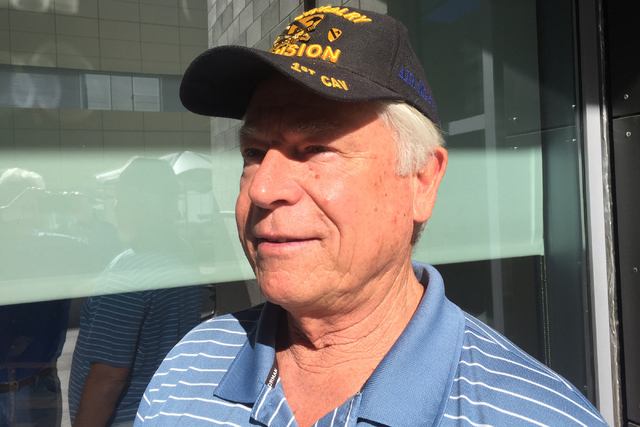

Army infantry veteran Mark Rohlffs, who served in the 1st Squadron 9th Cavalry, 1st Air Cavalry Division, couldn’t erase the sight of pulling dead American soldiers from returning helicopters in his air-mobile unit.

After he got home from Vietnam, he went for a walk with his father “and I was saying I’m having a hard time being around people. I’m uncomfortable.” His father told him, “You’re going to be all right.”

Rohlffs’ discomfort came from his mindset that people couldn’t imagine or wouldn’t believe what he had endured.

“When you’re in the jungle, your initial reaction to problems is to annihilate them,” he said. “It took a while to recognize and learn to live with incredible nightmares. It was like my whole torso was a knot of anxiety.”

Despite his own battle with multiple sclerosis that began in 1982, Kingsbury never let his condition get in the way of helping veterans.

They admired his courage and his sense of humor after he rolled into the weekly counseling sessions in his wheelchair.

“He always had a joke for us,” said Vietnam War Army 1st Cavalry veteran George Urias.

“I can’t say enough about Doc. He set my life on a good course. I like his honesty,” Urias said. “I hold that guy in the highest regard in my little world.”

In his humble demeanor, Kingsbury kept things about his own battles in perspective.

“I said to them, ‘It’s not a contest,’” he said. ”’If you’re suffering, you need help. If I’m suffering I need help. We’re all in it together. … The fact that you’re suffering does matter and we’ve got to do something about it.’”

Coslow said Kingsbury has been in a wheelchair ever since he’s known him.

“I guess it kind of inspired all of us because anything we had to deal with we could look at him,” Coslow said. “He gives 2,000 percent to the veterans.”

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2

PTSD EVOLUTION

There wasn’t a specific name for post-traumatic stress disorder when Dr. Steven Kingsbury first began working with combat veterans a few years after the Vietnam War ended in 1975.

PTSD didn’t become part of the VA’s vocabulary until the American Psychiatric Association’s manual for mental health disorders was revised in 1980.

Some symptoms had been described as “shell shock” or “war neuroses” for World War I veterans; or “combat stress reaction” from “battle fatigue” for World War II veterans, according the VA’s National Center for PTSD.

During the Korean War era, the association’s manual from 1952 made reference to “gross stress reaction” as a symptom of traumatic combat events. The diagnosis, however, was struck from the revised 1968 manual and replaced with an “adjustment reaction to adult life.” That was later described on the center’s website as “clearly insuficient to capture a PTSD-like conditon.”

In 2013, more than 500,000 veterans were receiving treatment for PTSD at VA facilities.