Four Nevadans share thoughts of Korean War armistice anniversary

News of the halt to hostilities echoed through the war zone at varying levels after delegates signed the armistice agreement to end the three-year conflict on the Korean peninsula 60 years ago today.

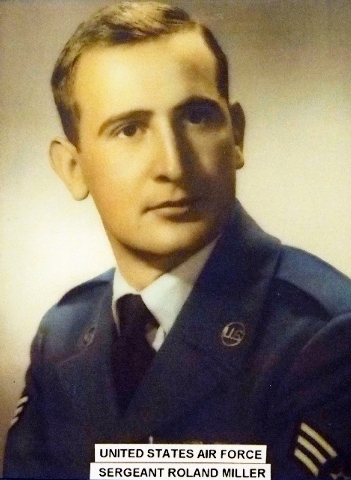

For Air Force veteran Roland Miller, one of four Southern Nevadans who fought in that war and shared where they were on that historic day, word of the armistice trickled out with little fanfare because his tent at Seoul air base wasn’t equipped with radios to receive the news.

“I used to lay in my bunk at night praying that (President Dwight) Eisenhower would put an end to the war,” said Miller, 82, who has lived in Las Vegas the past 35 years.

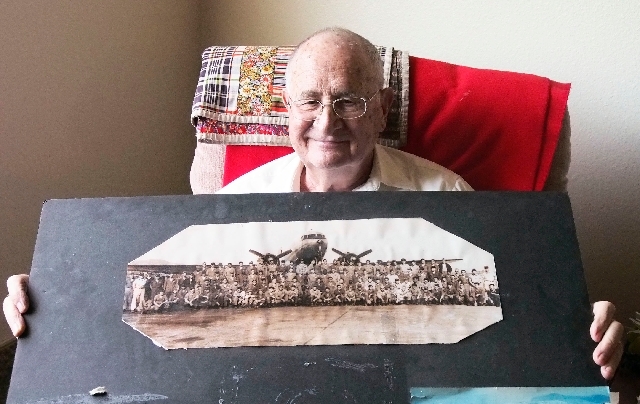

Raised on a farm in South Dakota, he decided to join the Air Force rather than be drafted. He arrived in South Korea in April 1953 to work as crew chief for a C-47 transport plane flown by his unit, the Kyushu Gypsies.

In the months leading up to the armistice, many of his crew’s missions involved transporting wounded from the battlefield to medical facilities in the region.

What he noticed about the armistice’s aftermath was the shift in missions from medical evacuations to taking USO performers to their show locations.

It was about this time that Miller became one of the lucky few who could say they walked away from an airplane crash in the Korean War. On that flight, as he did most of the time when they were flying, he was standing behind the pilots when the C-47 experienced a problem landing in rainy weather.

Something he had learned in training at Stead Air Force Base near Reno flashed through his mind.

“ ‘Remember one thing, Miller,’ ” he recalled his instructor saying. “ ‘If you’re going to be in a crash, get your back against something solid.’ So I got my back against the bulkhead.”

When the plane hit the ground, it slid on its belly, tearing off the landing gear. Fortunately, everyone survived.

“I was the first S.O.B. out of that airplane,” he said.

ON THE 38TH PARALLEL

Nineteen-year-old Marine Cpl. Vito Tomasino was dug in along the 38th parallel in a trench when the United Nations’ “police action” came to a halt with the armistice on July 27, 1953. Ten days earlier one of his buddies, Pfc. William C. Lastinger, had been killed on a night patrol.

“It was 10 o’clock at night when they actually made it official,” Tomasino, of Las Vegas, said.

In the weeks before signing, the Dragon Lady — an adversary radio personality akin to Tokyo Rose of World War II fame — had read Dear John letters within earshot of Tomasino’s unit. “She called us baby killers and tried to demoralize us.”

But on that July 27 evening her message was much different.

“She came over with some nice words about the troops. She said the Chinese soldiers and North Korean regulars were going to be coming over to the lines to hang gifts,” he said. “It was sort of surreal.”

With the cease-fire in force, North Korean soldiers showed up on the front line and hung little packages on the bushes. Aware that they might be booby trapped, the Marines didn’t touch them but sent ordnance demolitions teams in instead to secure the area.

Tomasino, of Long Island, N.Y., later joined the Air Force. He flew 128 combat missions as a fighter pilot during the Vietnam War but believes the Korean War “was really the last war we fought that was worthwhile.”

AFTER OUTPOST HARRY

The armistice agreement was signed by Army Lt. Gen. William Harrison Jr., of the United Nations Command, and North Korean Gen. Nam II, representing his country’s People’s Army and China’s People’s Volunteer Army. The agreement set up the repatriation of remaining war prisoners, established the demilitarized zone and ensured “a complete cessation of hostilities … until a final peaceful settlement is achieved,” a goal that has eluded North Korea and South Korea for the past six decades.

Keeping South Korea and its government intact didn’t come cheap. Nearly 37,000 U.S. military personnel died during the three-year conflict. About 7,900 remained unaccounted for, according to figures the Pentagon revised in 2000.

Army Pvt. Warren “Gene” Sessler fought in the last major battle of the war, the Battle for Outpost Harry. Now living in Henderson, Sessler was an 18-year-old rifleman from Detroit when he fought in the battle on June 11, 1953. For his heroic actions he was awarded the Silver Star.

Two days before the armistice, he was in a field hospital recovering from wounds from a mortar fire incident about a month after the Battle for Outpost Harry. Rather than staying in the field hospital for the armistice, he wanted to be with his unit, Charlie Company of the 15th Infantry Regiment.

“So I went AWOL (absent without leave) and hitched a ride back to the front line,” he said, recalling how he reached Charlie Company as the truce was about to take effect. He volunteered to drive an ammunition truck.

“Each side was firing large quantities of ammo up until midnight, then halted right on time,” Sessler said. He said a bag of loose ammo exploded as a soldier was hauling it to his truck.

“I assumed he was killed,” he said. “Many hand grenades that were being removed from trenches and bunkers had the safety pins bent straight for easy withdrawal during attacks. So it was dangerous duty.”

SAILING ON

Philip Varricchio had experienced his share of dicey naval assignments when he was engineering officer of a landing craft that patrolled the mouth of Manila Bay in the Philippines during World War II.

When the Korean conflict heated up, he was among the first Navy officers called in. He served as chief navigator for 40 tank landing ships (LSTs) that plied mine-infested waters during the 1950 Inchon invasion.

Before they could sail, though, the ships that had been converted to fishing vessels by the Japanese had to be re-equipped with war-fighting gear.

“They were full of fish tanks and squid tanks,” Varricchio, 90, said from his Henderson home.

The task of delivering troops and supplies to Busan on South Korea’s southeast coast was often more dangerous than his World War II experience because the waters were more concentrated with mines.

“That was all heavy stuff in those months,” the former lieutenant said.

After 13 months of active duty, Varricchio accepted the Navy’s offer to return to the United States for his honorable discharge with other prior-service sailors.

He had just opened up his accounting business in Pennsylvania when he heard the news about the armistice.

Looking back, he sees the stalemate that has persisted for 60 years and wonders whether the Korean War legacy will ever be resolved.

“We still have 30,000 troops on guard on the 38th parallel. It’s a joke with that million-man (North Korean) army standing by.”

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.

RELATED STORY

Friendship forms between pair from different sides of Korean War (with video)