For Las Vegas WWII vets, Memorial Day is another day to be thankful

Despite their obvious differences — one is a retired African-American bus driver from the Deep South; the other is an Italian-American ex-liquor distributor from New York — Las Vegas World War II veterans Vernice “Lucky” Gaar and Frank Costa have a lot in common.

They both fought in the Army in Pacific theater, lost buddies who fought alongside them and have lived with the mental scars from their war experiences for more than 70 years.

But it took a three-day Honor Flight trip to Washington, D.C., in April to introduce the two old soldiers to each other and produce a moment as bronze-worthy as the war memorials they were visiting.

In a driving rainstorm on April 22, Gaar, 91, pushed the 99-year-old Costa in his wheelchair to place a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns as a soldier played taps.

“It just opened up,” Costa said of the rain in a May 9 interview at his southwest Las Vegas apartment. “That’s when (Lucky) says, ‘God is crying.’”

Both said they had flashbacks to the carnage they witnessed.

“I wasn’t thinking about it anymore then all of a sudden it’s coming back again,” Costa said.

Gaar, whose sense of humor seldom deserts him, said he tried to stay focused on the task at hand and was thinking, “I hope I don’t hit a bump and dump him … out of his seat.”

“The thing I’m thinking about now,” he said sitting last week in the den of his east Las Vegas house, “is how lucky I am and how lucky the guys are that came back. Every Memorial Day I think about that.”

Fighting ‘there and back’

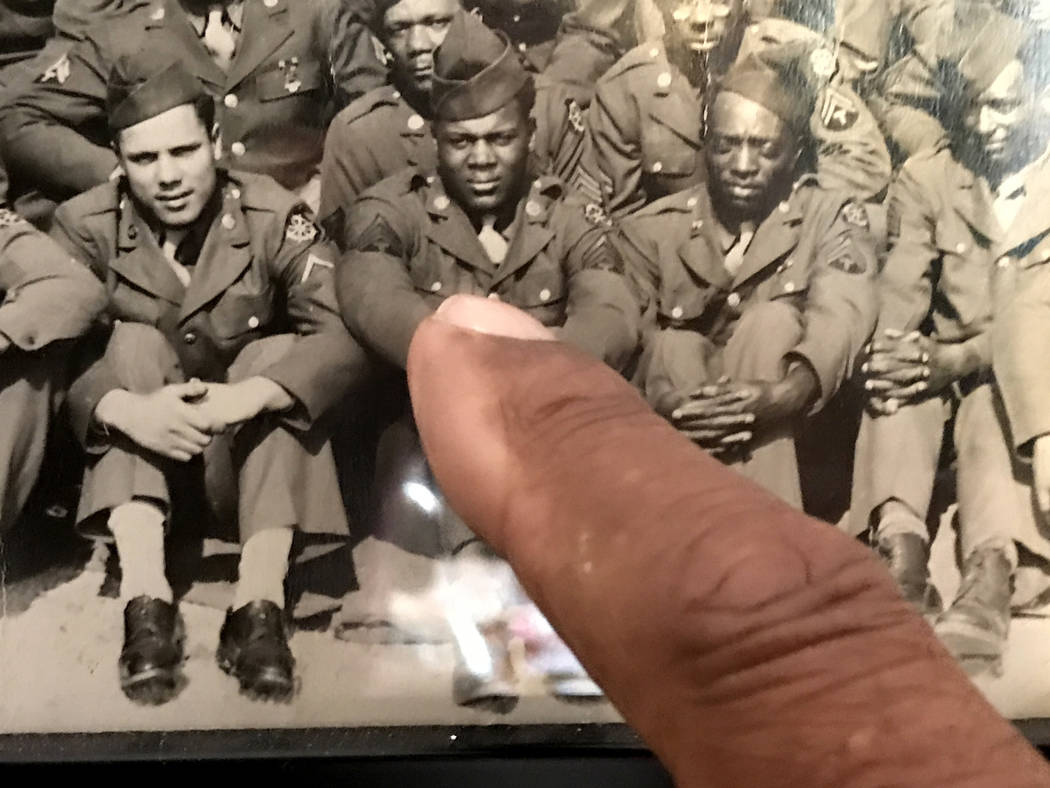

Gaar served in one of the first mixed-racial units in World War II — the 129th Port Battalion. It was a natural step for the former Grambling State University draftee from Ruston, Louisiana.

After all, he was raised in a mixed-race family. His grandmother, Sara “Sallie” Gaar, an African-American and native American doctor, from Redbird, a former all-black town in the Oklahoma Territory, married Alex Gaar, a Caucasian from Sweden.

The younger Gaar’s skill driving farm equipment landed him a technical sergeant’s spot driving landing craft and six-wheel amphibious trucks, DUKWs, commonly known as “ducks,” to shuttle soldiers, Marines and supplies for beach landings.

“We had to fight our way there and back,” he said. “Once on the way in we got to fighting with those Zeros that were coming around. I was in the crow’s nest shooting at the planes and and everybody else was shooting, and all of a sudden we were blown up.”

He was transported unconscious to a field hospital. “I didn’t have no dog tags because they were blown off of me. And they were calling me lucky to be alive because all the rest of them got killed.”

When he came to “they were calling me ‘Lucky,’ because they didn’t know my name. I look around and say, ‘Who’s Lucky?’ They said, “That’s you.’ I said, ‘No. My name is Vernice.’”

‘Didn’t even get a scratch’

Costa, the son of Italian emigrants who grew up in Geneva, New York, before being drafted, rarely talked after the war about his combat experience on Angaur Island in the Pacific.

An ammunition handler on a tank crew with the 81st Infantry “Wildcat” Division, Costa said that when they landed “the beach was covered with bodies. That’s when you really get scared.”

“When we got on the railroad track with the tanks we got a little ahead of the guys who were protecting us. … As the Japanese come sailing in front of our tank, me and two other boys jumped over the side of the hill down in the gutter to miss the bombing and the strafing.

“One of the boys got hit in the head and the other guy got it in the chest,” he said, his eyes welling with tears. The one who was hit in the helmet lived but the other died instantly, he said.

“I didn’t even get a scratch and I was right between the two guys. That’s when the medic says to me, ‘God’s on your side.’ And I said, ‘Yeah. I’m gonna live to be 103.’”

War’s end

Gaar was welcomed back to his outfit at Okinawa “by a bunch of guys I didn’t know” and was there when the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki that led to Japan’s surrender.

“All of a sudden (you could hear) all the sirens on the ships and everything; Tokyo Rose was blastin’ like I don’t know what they were saying,” he said. “We didn’t know what the hell they were talking about. They were saying, ‘The war was over with. The war was over with.’”

Costa was on Leyte Island in the Philippines when the war ended. “I wanted to go home but instead they sent me to Japan,” for post-war duty he said.

Both men say they are still amazed that they survived the horrors that claimed so many of their fellow soldiers.

Gaar said he “thanks God every day.’

“I say my prayers every night and I thank God for the people that helped me, and the people that’s still helping me,” he said. “Be thankful. Don’t take anything for granted. And help those that you can. When you see somebody that needs help, don’t turn your back on them.”

Costa simply says, “I guess God was on my side.”

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Follow @KeithRogers2 on Twitter.

Memorial Day roots

Memorial Day began as Decoration Day after the end of the American Civil War in 1868, when, originally, members of the Grand Army of the Republic would visit and decorate graves of fallen service members with flowers.

The first national observance was at Arlington National Cemetery that same year, although multiple cities claim to be the “birthplace” of the holiday. In 1966, President Lyndon Johnson and Congress declared Waterloo, New York, the official birthplace.

Memorial Day traditionally has been observed near of the end of May when flowers are in bloom. The date was officially switched from May 30 to the last Monday of May after it was declared a federal holiday in 1971.

Source: Department of Veterans Affairs

About Honor Flight

Honor Flight Southern Nevada was founded in 2013 as a part of the national Honor Flight Network to honor America’s veterans for their sacrifices.

The next local flight trip is scheduled for Oct. 27-29 for World War II and Korean War veterans.

For application information call 702-749-5933 or visit the organization’s website: http://honorflightsouthernnevada.org