Ex-POW recalls the day he ‘died in 1944’

Americo Benetti never thought he’d live to see another Veterans Day, or Armistice Day as it was called when he served in the Army Air Corps during World War II.

“I’m happy that I’m still here,” the 93-year-old ex-prisoner of war said.

“Somebody was praying for me, I’ll tell you, because I died in 1944,” he said at his Las Vegas home Nov. 4.

On Veterans Day today, Benetti said he will “probably sit here and I’ll reminisce” not only about his wife and three sons, all who served in the Army, but also about “all the soldiers that got killed in the war.”

“I’ll reminisce about the pictures of flying over the oil fields and seeing all the parachutes from the first three waves of aircraft going through the black smoke and the fire,” he said about his crew’s last flight.

Little did he know when he was a 7-year-old boy who immigrated from Italy — “my dad and Mussolini didn’t get along” — that he would return to his native soil 16 years later to fight Benito Mussolini’s fascist forces, who had teamed with Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Germany.

After graduating from high school where his family settled in California’s San Fernando Valley, he joined the war effort and became a ball turret gunner, a soldier who mans twin .50-caliber machine guns from the bottom of a bomber.

He was eventually assigned to the 495th Bombardment Group’s 758th Squadron, to be part of a crew with tail gunner Ernest Gordon Liner of Hillsborough, North Carolina.

Moron’s last mission

“We saw one plane blow up and two others take hits. On three engines, we could not keep up with the formation,” Liner wrote for the group’s website, describing the final mission of their plane, The Moron, to bomb synthetic oil targets in Blechhammer, Germany.

“After the bombs were dropped, we were attacked by four fighters and lost another engine,” wrote Liner, who died eight years ago.

The B-24 with pilot Jerry Cullison of Pittsburgh, Ernie Liner, “A.J.” Benetti and seven other crew members was returning Aug. 22, 1944, to their base at Cerignola, Italy, where they slept in tents at the edge of an almond orchard.

“Everything was good until we got over Hungary,” Benetti said. “That’s where the Nazis had their aircraft waiting for the stragglers. … I saw the (fighter) coming at me from the tail. This was in range. I was shooting at him, and I know I hit him because I’m looking at the tracers.”

While Benetti’s guns were blazing, Liner said he “shot the plane attacking our tail and it exploded. The fighter on the side killed (waist-gunner Tom) Tomlinson and (Benetti) the ball turret gunner was hit, giving the German fighters two positions not covered.”

From his perch under the belly, Benetti saw two flashes from each wing of the attacking plane.

“All of a sudden my leg, my thigh, my arm, my left shoulder and my left eye was gone,” he said about the bullets that ripped through his flesh.

Then the German pilot came back and strafed the bomber from front to back.

“I got my chute on. I stood up … and saw one of my buddies in the middle of the airplane. He’s sitting down as if he was praying, but he was dead by the big window,” Benetti said.

Liner moved Tomlinson’s body from escape door “so we could get out,” Liner wrote.

Benetti used his right leg and arm to emerge from the bottom turret. As he stood up, he fell out of the bomb-bay doors.

“I don’t remember how I opened the chute. I don’t remember nothing,” he said.

‘Gobble, gobble, gobble’

Benetti survived the descent, landing in Hungarian farmland.

“I lay there and I hear, ‘Gobble, gobble, gobble. Gobble, gobble, gobble.’ Oh, I landed in a turkey farm. In my mind I see two turkeys. I see the red crest and the beaks coming at my face,” he recalled. “I woke up and I didn’t see no turkeys. All there was is people with pitchforks and clubs all around me. And I passed out, again.”

He woke up to the sight of “three German officers in their gray uniforms. They were putting me on a cart and I passed out again.”

The next time he came to he was in a prison hospital in Hungary.

“I’m in a daze and all of a sudden I see this young German officer, coming at me and saluted me.

“I said, ‘Who are you?’ He says, ‘I’m the pilot that shot you. That’s why I’m here. To see if you were dead or what. I followed you all the way down because I knew you were dead.”

Benetti told his adversary, “This war is not between me and you. And he says, ‘Yeah I know. Get well. I’m glad I did not kill you.’ Then he saluted me again and took off.”

Benetti spent the remainder of the war in Europe, hopscotching to prisoner-of-war hospitals and camps. He lost 60 pounds during the ordeal, weighing 120 by the time Gen. George Patton’s troops liberated U.S. war prisoners in the spring of 1945.

Family affair

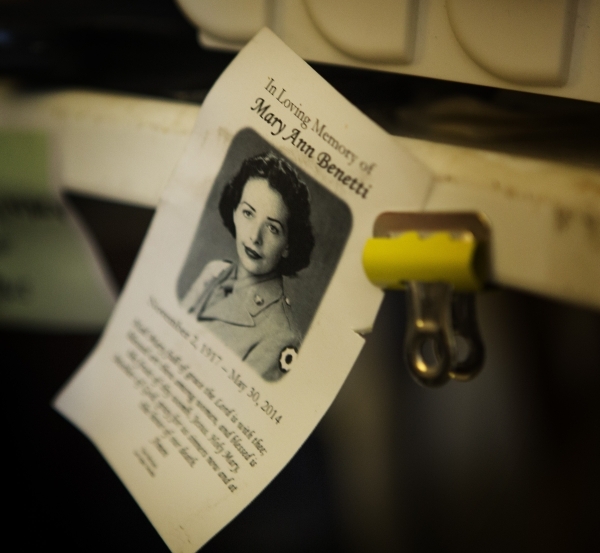

He was sent to a hospital in Modesto, Calif., where he met his future wife, Mary Ann Frederico, a Women’s Army Corps surgical technician.

Their three sons all served in the Vietnam War. The oldest, Greg, was an Army medic for the 82nd and 101st airborne divisions. He died of cancer related to Agent Orange exposure in 2011 and is buried at the Southern Nevada Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Boulder City next to his mother, who died in 2013.

Steve Benetti, 66, was an Army reconnaissance aircraft crew chief. His brother, Jan, 62, served as an Army radio operator.

Steve Benetti said he will have “a lot of mixed emotions” on Veterans Day.

“I’m very proud of my family,” he said Tuesday, from Como, Colorado. “I feel very proud to have been able to serve my country. I feel very sad that we’ve lost so many people and a lot of times I’m not sure why.

“You wonder if there was another way to go about it so the lives wouldn’t have been lost,” he said.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2