DRONE WARRIORS

INDIAN SPRINGS — From the vantage point of a remotely piloted Reaper spy plane soaring 20,000 feet over southern Afghanistan, the terrain below looked harmless Monday, much like a GoogleEarth view of the gravel washes near Red Rock Canyon.

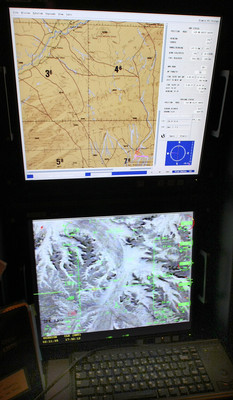

There were mountains and valleys and bald fingers of high desert peninsulas jutting across the monitor of Lt. Col. Jon Greene’s computer console.

"When we’re over a target we loiter," he said.

That’s when the big lenses come into play, ones that let him see something the size of a car or a house as if peering through a straw.

"We’re in constant communication with ground forces," Greene said. "They’re watching our video."

Next to him sat the sensor operator, Royal Air Force Wing Commander Andy Jeffrey, the guy who would hold the laser beam on the target for bombs or Hellfire missiles that would rain down upon the target should that be necessary.

The target in this part of Afghanistan might not be as harmless as the land’s surface looks. The black blotches on the screens might be trucks or Taliban militants toting homemade bombs and automatic weapons.

They could be men with small shovels ready to dig holes for pressure plates that would detonate bombs if a convoy rolled over them.

"Currently we’re working in infrared," Jeffrey said as he took a swig of water from a plastic bottle next to his seat.

While an air conditioner inside the highly secured room blew cold air down the back of Jeffrey’s olive-drab coveralls, the Royal Air Force Reaper was cruising 10,000 miles away at 160 mph.

It was dark, 10:30 at night in Afghanistan, but it was broad daylight outside the concrete-block ground control station at the small Nevada base, 45 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

This was the first time ever that commanders from U.S. and British Reaper squadrons flew a joint combat mission.

And they were doing it in front of cameras from the British television and print media. It was the first peek at the combat role that the little-known British unit, 39 Squadron, was performing since its debut at the base a few years ago.

Like their American counterparts, the work of the Royal Air Force pilots and sensor experts hinges on their ability to react with only a couple of seconds’ delay in the satellite relay from the Reaper’s high-tech transmission system.

The mission Monday marked a turning point in military aviation history, one that comes in an era that Col. Christopher R. Chambliss, commander of the U.S.’s 432nd Wing, equated to the time nine decades ago when military leaders were beginning to grasp the value of piloted aircraft.

"I kind of look at this as the 1920s of manned aviation," he said, standing on the tarmac at Creech Air Force Base in front of a gray, MQ-9 Reaper, one of roughly 10 of the armed, remotely piloted spy planes ready for combat operations.

The Reaper, he said, can fly higher and faster and carry more weapons than the MQ-1 Predator, the Reaper’s little brother. Since the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the Predator has been the coalition forces’ drone workhorse in the war on terrorism.

But the MQ-9 Reaper is much better suited for the job in Afghanistan, where the spy game is conducted at higher altitudes and brute force is needed from 500-pound bombs in addition to Hellfire missiles, like the Predator carries.

"We’re a multi-role," Chambliss said. "That’s why there’s an ‘M’ in MQ-9 and MQ-1."

Since arriving in Afghanistan in September, the U.S. Reaper has been busy dropping bombs or firing missiles.

"We’ve been employing weapons with it quite frequently. Not every day, but often," Chambliss said.

The British Reaper arrived in the war zone a month later last year.

"It’s a matter of course that we include our British partners in everything we do," he said. "Our British coalition folks are sitting side-by-side."

Inside the ground control station, Greene and Jeffrey continued to look for targets.

A Royal Air Force officer, who asked that he not be named for security reasons, led British news crews into the room.

"Behind this door is Afghanistan, believe it or not," said the officer, whose nickname is Tiger.

Later, Tiger returned to round up the reporters.

"Sorry about the rush," he said. "We’ve got a little thing going on right now."

ON THE WEB Reaper slide show