Creech drones having ‘incredible impact’ in war on terror

INDIAN SPRINGS — When they chose his fighter pilot’s nickname, Case Cunningham’s comrades gave him the handle “Basket,” as in basket case.

But if they had focused on “unique look” or “unique ability,” two other common techniques for bestowing “Top Gun” nicknames, he’d more likely be known as “Cool.”

The 45-year-old Air Force colonel’s steady demeanor is on display daily in his role as commander of the 432nd Wing and the combat operations unit, the 432nd Air Expeditionary Wing, at Creech Air Force Base.

As host to the 432nd Air Expeditionary Wing, the tip of the Air Force spear in the nation’s global war on terrorism, Creech is arguably the most active military base of the dozen or so in the United States engaged in day-to-day overseas combat operations.

“When it comes to fighting our nation’s wars … I think it would be hard to find a base in the United States Air Force in the continental United States that is more engaged … defending America every single day,” he told the Review-Journal last week at the wing’s headquarters office.

Cunningham is starting to reflect on his two years as commander of the 432nd Wing as he prepares for a new assignment beginning this summer: commander of the 18th Wing, Pacific Air Forces, in Japan as a brigadier general.

“Being around those airmen is pretty incredible,” he said. “This is something that the people of Las Vegas and Indian Springs can be incredibly proud of, that these airmen, when they come to work every single day, are making an incredible impact in the fight (against terrorism),” he said.

“The amount of territory that’s been taken back overseas from terrorist organizations is absolutely remarkable,” he added, referring to recent gains against the militant group Islamic State, also known as IS, and other terror groups in the Mideast and Asia.

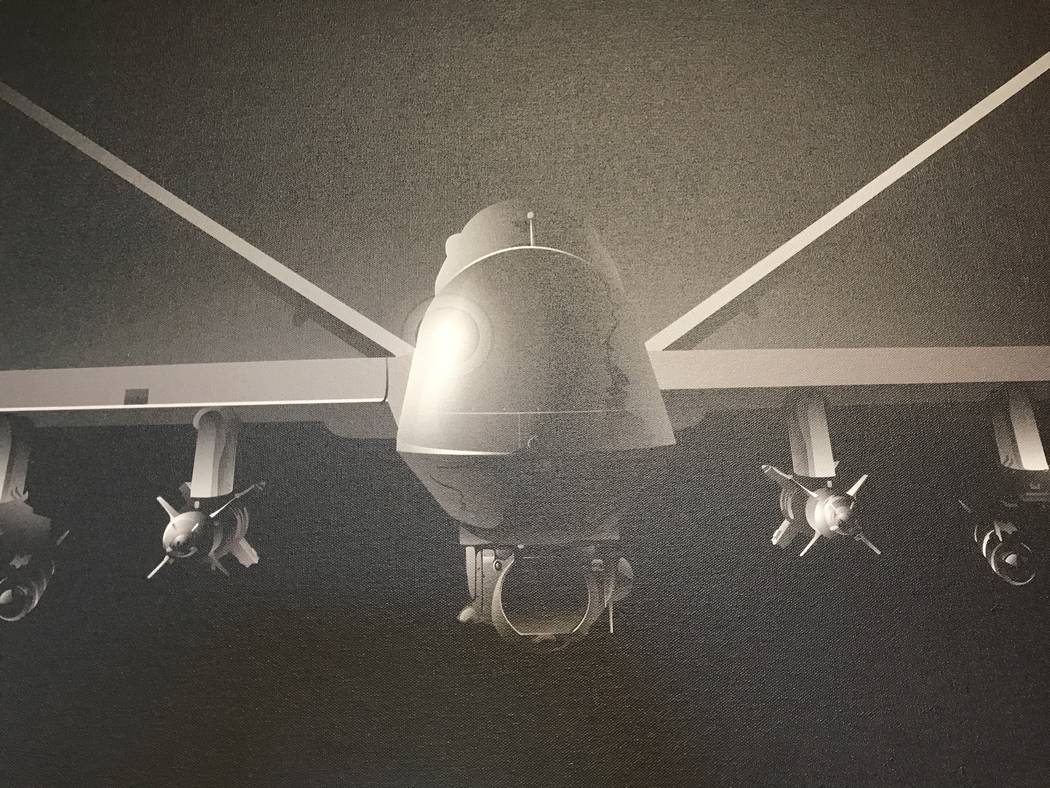

When Cunningham hands over the Creech keys to his successor, Col. Julian Cheater, it will require a big keychain. The 432nd commander oversees more than 130 remotely piloted aircraft, including MQ-9 Reapers and the jet-powered “Beast of Kandahar” RQ-170 Sentinel reconnaissance aircraft, and a staff of 2,500 regular Air Force, Reserve and National Guard airmen in addition to 1,000 civilian employees.

From tent city to drone hub

The Creech base was established in 1942 as an Army “tent city” military training camp and transferred to the Air Force in 1950 as Indian Springs Air Force Base, more commonly referred to as Indian Springs Auxiliary Airfield. It was renamed in 2005 for the late Gen. Wilbur L. “Bill” Creech, the so-called “father of the Thunderbirds,” who preserved the Air Force’s aerial demonstration team after the deadly “diamond formation” crash of four aircraft at the base in 1982.

The base, 45 miles northwest of Las Vegas, has since evolved to be the U.S. hub for remotely piloted aircraft combat operations in the Middle East and Afghanistan.

“We do our combat operations from the United States, and certainly that is (a) unique way we employ air power,” Cunningham said, standing in his office with a picture-window view of a runway where pilots of MQ-9 Reapers and some older MQ-1 Predator drones practice touch-and-go landings.

The buzzword for drone surveillance and combat operations controlled thousands of miles away from combat zones is “RSO,” short for remote-split operations. A Reaper is launched by an air crew at an overseas base before control of the aircraft is handed off via satellite links to a pilot and a sensor operator at Creech or other locations in the United States.

The Creech unit is now phasing in new “block-five” Reapers, which have finlike winglets at the tip of each wing to increase lift, reduce air-flow drag and improve fuel efficiency. They also have enhanced communication systems that make them better-suited for multi-role missions such as search and rescue, strike coordination for close air support and reconnaissance and surveillance.

The remotely piloted Reaper can carry four Hellfire missiles and two 500-pound, GPS- or laser-guided bombs under its 66-foot-long wings.

The block-five Reapers are replacing the smaller MQ-1 Predator, which has long been the Air Force’s remote workhorse. The last of the Predators, the MQ-1B, will be phased out in the spring of 2018, Cunningham said.

Until recently, Reapers carried only missiles and laser-guided bombs. But now they can be armed with GPS or Global Positioning System munitions.

“Now we have all-weather capability,” Cunningham said. “So we could be above a cloud … and drop a weapon on very precise coordinates. Whereas before, with a laser-guided munition, we could not do that.”

Fighting a war from afar

Fighting a war with remotely piloted aircraft is similar to fighting with manned aircraft, Cunningham said.

“There’s way more ‘similar’ than there is ‘different’ about it. At its very heart it’s air power. It just happens the cockpit we sit in is located in the United States. … But all the rules of engagement, all the thought processes of our air crews … (are) exactly the same as it would be if you’re sitting in the airplane over the battlefield,” he said.

Cunningham pushes back against critics who claim that drone strikes cause more civilian casualties than manned aircraft, saying reports from the scene often overstate the numbers.

As an example, his staff points to a tripod-mounted mortar tube on display in the lobby of the 432nd Wing headquarters. The enemy combatant seen using it to shell U.S. troops in the Middle East was later seen on video shot from a drone unloading the mortar from the trunk of a car and throwing it into a waterway. That meant that when he was killed by a Hellfire missile a short time later, he had the appearance of an unarmed civilian until forces on the ground recovered his weapon.

Cunningham said he believes that protesters who repeatedly demonstrate against drone warfare at Creech are “vastly misinformed.” But he has no problem with them expressing their opinions.

“While I don’t agree with what they are saying, I feel very good knowing that we actually provide the umbrella of freedom under which they can exercise their right to free speech,” he said. “For someone wearing a uniform, that’s pretty powerful in itself. They cannot do that same thing in any number of other countries across the globe.”

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Follow @KeithRogers2 on Twitter.

Predator milestones

• 1995 — RQ-1 Predator A models used in spy missions over Kosovo and Southwest Asia

• 2001 — Predator fires first laser-guided missile to destroy a tank from 3 miles away at Nellis Air Force Range.

• 2003 — Chum-1 and Chum-2 Predators used as decoys to locate anti-aircraft sites in opening days of Iraq War.

• 2003 — 15th Reconnaissance Squadron uses remote-controlled aircraft to help rescue missing U.S. soldier Jessica Lynch.

• 2003 — MQ-1 Predator makes first “kill” in the Iraq War, destroying anti-aircraft site near Amarah with Hellfire missile.

• 2003 — Predator controlled from Nellis Air Force Base helps soldiers capture Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein.

• 2004 — Predator from 17th Reconnaissance Squadron spots al-Qaida’s Osama bin Laden near a cave in Afghanistan.

• 2008 — Predators at home and overseas complete 400,000 hours of flight.

• 2011 — U.S. Air Force remotely piloted aircraft (RPAs) achieve 1 million flight hours.

• 2016 — Air Force RPAs surpass 3 million flight hours.

• 2017 — MQ-1 and MQ-1B Predator fleet slated for “sunset” phaseout in spring of 2018.

Case Cunningham’s career

• 1994 — Bachelor’s degree in political science, U.S. Air Force Academy, Colorado

• 1996 — F-15C training, Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida

• 1999 — USAF Weapons Instructor Course, Nellis Air Force Base

• 2000 – 2002 — Flight commander, 27th Fighter Squadron, Langley Air Force Base, Virginia

• 2002 – 2004 — Flight commander, 433rd Weapons Squadron, USAF Weapons School, Nellis Air Force Base

• 2004 – 2005 — Commander aide-de-camp, Air Warfare Center, Nellis Air Force Base

• 2007 – 2008 — F-22A Raptor training, Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida

• 2008 – 2009 — Operations director, 43rd Fighter Squadron, Tyndall Air Force Base, Florida

• 2009 — F-16 training, Luke Air Force Base, Arizona

• 2010 – 2012 — Thunderbirds air demonstration team, commander-leader, Nellis Air Force Base

• 2012 – 2013 — Vice commander, 451st Air Expeditionary Wing, Kandahar Airfield, Afghanistan

• 2013 — Ph.D. military strategy, Air University, Maxwell Air Force Base, Alabama

• 2013 – 2015 — Special assistant to the director, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency

• 2015 – 2017 — Commander, 432nd Wing / 432nd Air Expeditionary Wing, Creech Air Force Base