A century after World War I, Las Vegas hosts a remembrance

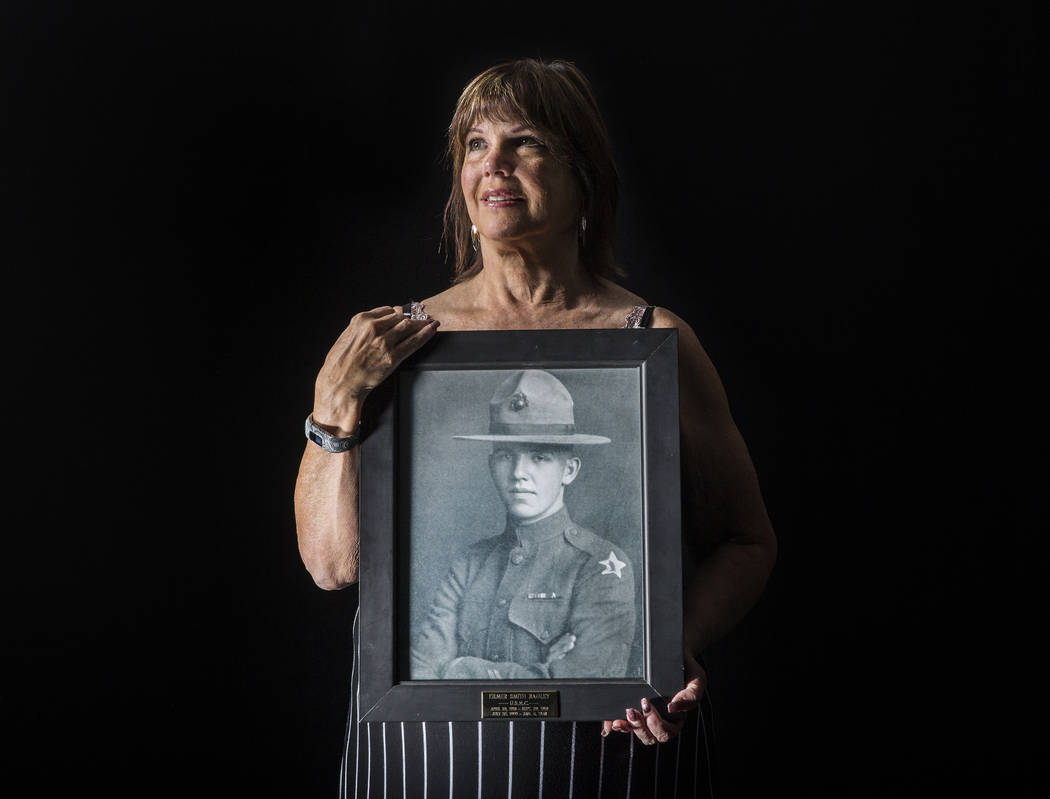

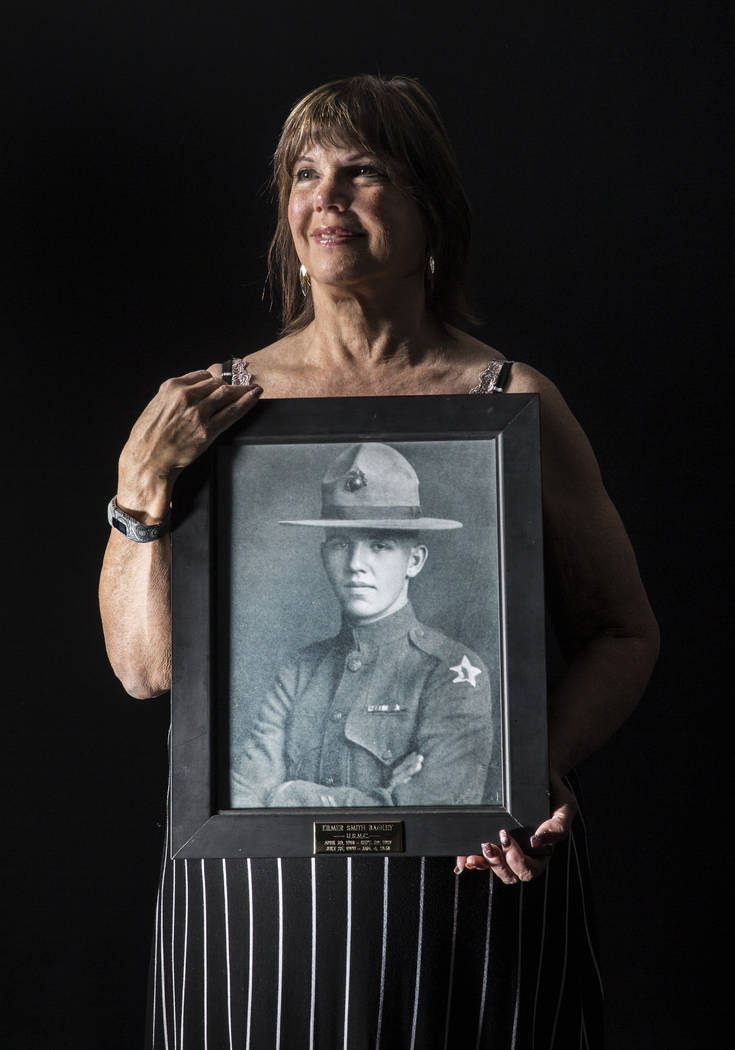

Pvt. Kilmer S. Bagley “hated the damn war but he loved the Marines.”

And like all Marines, says his daughter, he wanted to make a difference.

Bagley’s story, the subject of a permanent exhibit at the Leatherneck Club bar and grill in Las Vegas, is perhaps the most poignant local relic of World War I available for viewing on the 100th anniversary of the U.S. declaration of war on Germany on April 6, 1917.

The “Letters from a Marine” display uses Bagley’s own words and those of his father to tell the story of the young Minnesotan’s enlistment in the Marines and subsequent battlefield experiences in France.

Bagley was a high school senior in Duluth, Minnesota, in 1915 when German U-boats torpedoed the British ocean liner RMS Lusitania, killing 1,198 passengers and crew, including 128 Americans.

“It’s a shame we don’t help,” he told his dad, physician William Bagley, at the time.

‘Unfit for service’

The younger Bagley decided to do something himself, dropping out of high school soon afterward and trying to enlist in the Canadian military, which had declared war on Germany in 1914. He was rejected as “unfit for service,” his father wrote.

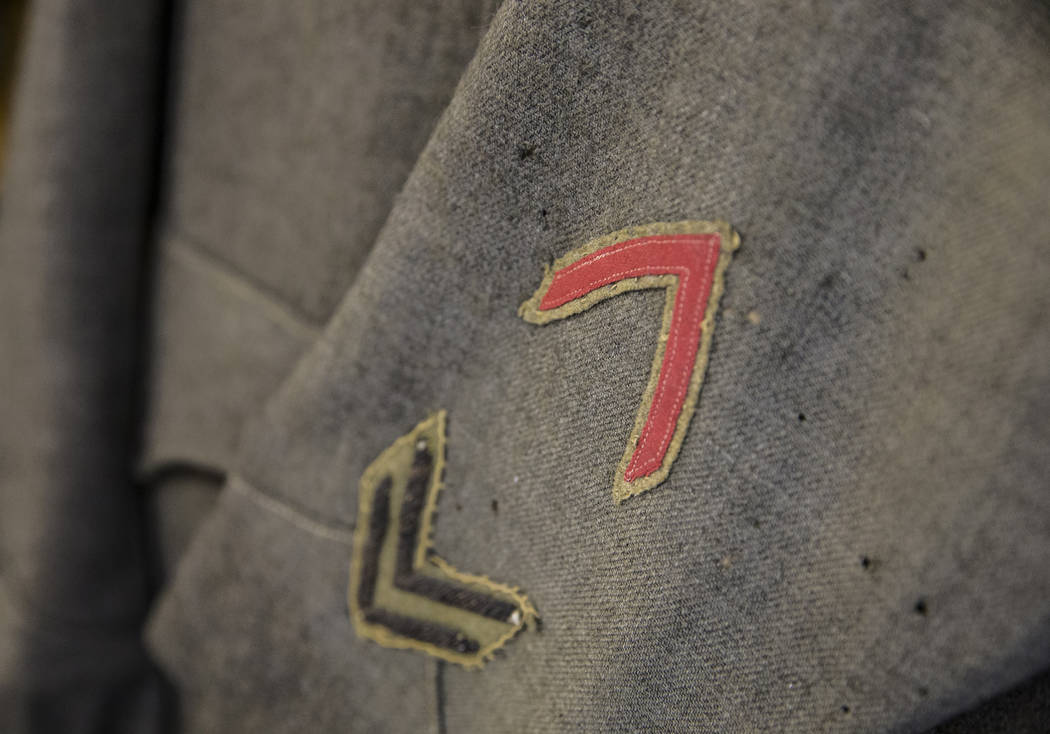

He returned to Duluth and finished high school, then enrolled at the University of Michigan before dropping out again and joining the Marines. And not just any unit, but the storied 5th Regiment, 2nd Marine Division led by Maj. Gen. John A. Lejeune.

Bagley traveled with the regiment to France, writing frequently to his loved ones back home. His letters from the battlefront simultaneously convey fear, loneliness and bravery:

Aug. 8, 1918

Dear Father and Mother:

I am well and near the front. I am the only one of the Company from Paris Island in this regiment so I feel quite alone.

I am now joined with the famous old Marines who started this drive against the Germans. … I have had my first experience with cooties already. I will have to stop as we marched most of last night and may march tonight, so I need some sleep.

With love, your son,

Kilmer

Bagley fulfilled his desire to make a difference.

He later wrote that he went “over the top” of the front line trenches in four major battles — at Saint-Mihiel, Champagne, Feloc and in the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. In fighting in Champagne, he destroyed two German machine gun nests and was awarded the esteemed French Croix de Guerre medal.

Despite the near constant danger and horrific conditions, Bagley remained upbeat in his letters home.

“I hope the flu hasn’t hit you people as hard as it has the Army,” he wrote two weeks after the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918.

Gassed during fighting

It was only on Christmas Eve, in a letter sent from “Across the Rhine,” that he hinted that his health was not good.

“I got my usual cold this year and am now in bed in a field hospital,” he wrote. “… The doctor calls it laryngitis because I can’t talk.”

The cold was actually the after-effects of being gassed during the assault on Blanc Mont Ridge in early October, when the 2nd Division fought with the 4th French Army to recapture the high point of the rolling Champagne terrain.

Bagley arrived in New York aboard the ship, Leviathan, with American Expeditionary Forces commander Gen. John J. Pershing on Sept. 9, 1919, and eventually returned to Minnesota. But his health never fully recovered. He died on Jan. 4, 1948, at 47, a delayed victim of chemical warfare.

“They figured he was gassed during the war. His lungs were never good after that,” said Jessie Greene, 90, who was 21 when her dad died.

“I’m in a crying mood thinking about my father,” she said by phone last week from Hickory, North Carolina. “He was perfect in every way. He died too early.”

“Letters of a Marine,” compiled by Bagley’s mother, Marian, includes notes and a heart-wrenching epilogue written as a letter from William Bagley to his son.

‘It isn’t possible!’

“I saw you die. It isn’t possible!” he wrote on Jan. 9, 1948. “You came home, married — have four fine children and established yourself successfully in the business world with wide respect of your Fellows.

“Now you have left us, and we are to be lonesome for you until we have fought the good fight and are taken to our reward.”

Bagley’s items were donated to the Leatherneck Club as a tribute to his service by his granddaughter, Susan Delaney , a Navy veteran, and her husband, Bill Delaney, who have lived in Las Vegas for 23 years. Like Bagley, Bill Delaney served in the storied “Warrior” patch 2nd Marines.

Having the items on public display “speaks to what we think of this country. It continues the legacy,” Susan Delaney said.

Added Bill: “He was very patriotic. He was willing to die and he did die for this country. To me he was a hero then and he’s a hero now.”

The war memorabilia museum at the Leatherneck Club, 4360 W. Spring Mountain Road, is free and open to the public every day from 11 a.m. to 11 p.m.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Follow @KeithRogers2 on Twitter.

Vestiges of Great War

There are few visible signs of the Great War remaining in the Las Vegas Valley, and no local public observances apparently are planned to mark Thursday’s centennial of Congress’ declaration of war against Germany on April 6, 1917.

But here are some public attractions for those looking for a good spot for a moment of silence or to bone up on history:

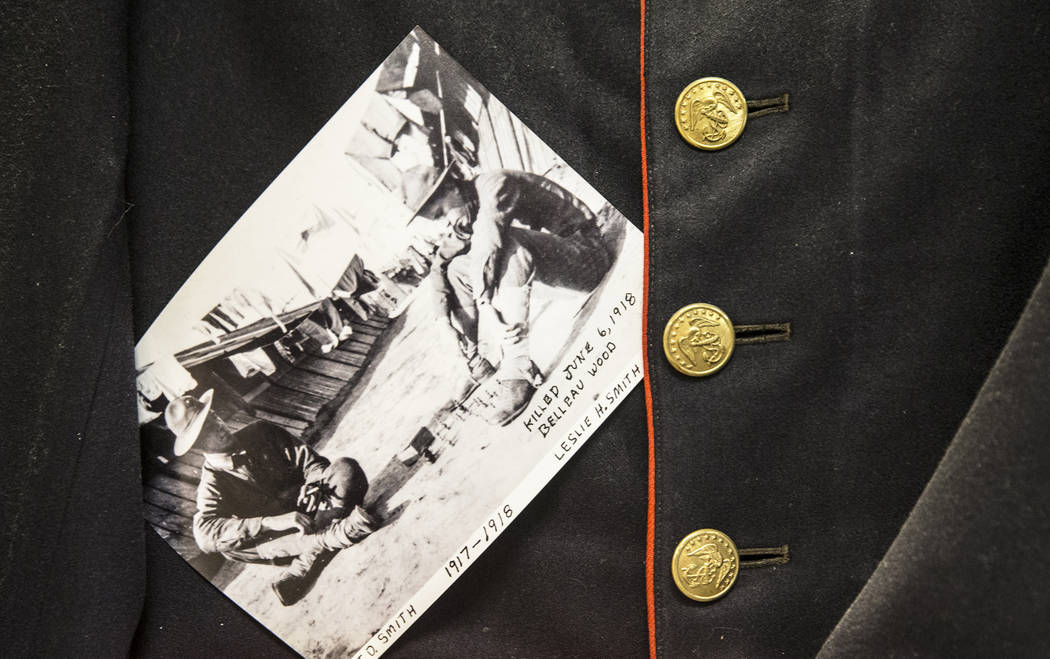

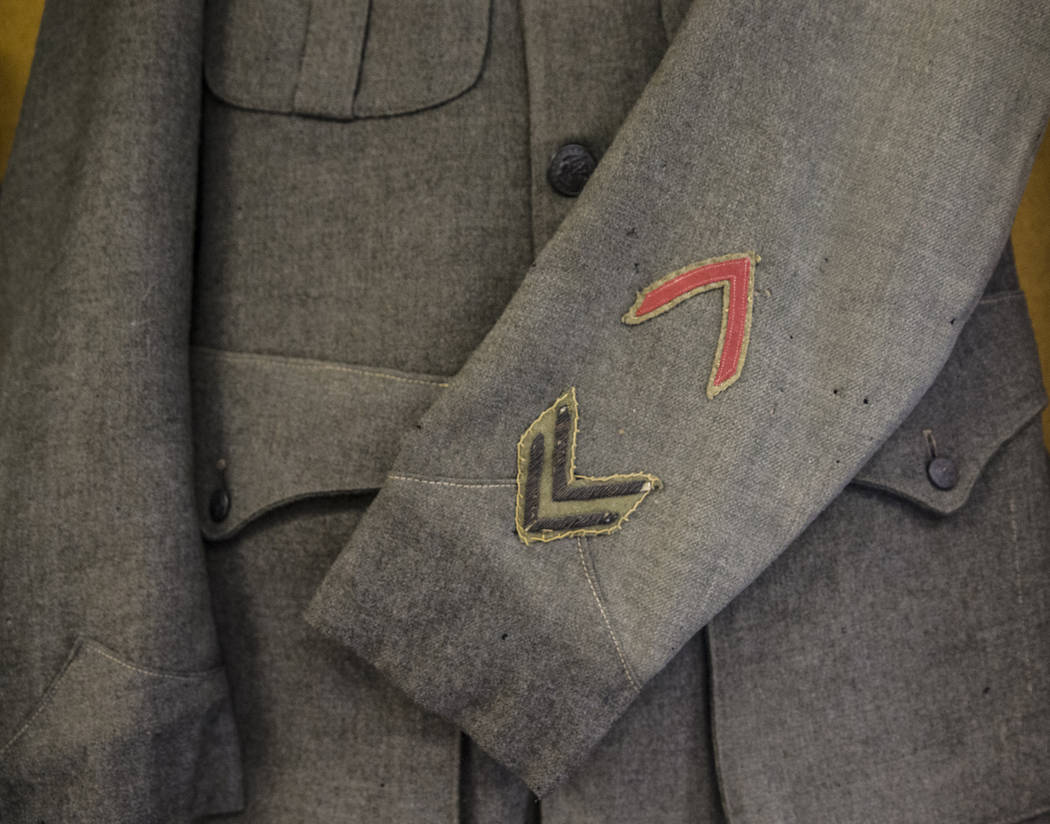

- The Leatherneck Club has the Las Vegas Valley’s most extensive collection of Marine artifacts from World War I and other conflicts. Pvt. Kilmer Bagley’s service photo and “Letters from a Marine” are displayed near the club’s entrance, along with photographs, gas masks, uniforms, weapons and other memorabilia. The club’s museum, 4360 W. Spring Mountain Road, is free and open to the public every day from 11 a.m. to 11 p.m.

- In downtown Las Vegas, a 1918 French artillery piece that had wooden-spoke wheels until they rotted away sits outside American Legion Post 8, 733 N Veterans Memorial Drive. The post offers free public viewing of uniforms and photos from the World War I era along with a display of a rare Post 1 garrison cap from France. Post 8 is open from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m. Monday through Saturday, and from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. Sunday.

- A few blocks away, on the southwest corner of Las Vegas Boulevard and Bonanza Road, is the 1952 American Gold Star Mothers of Las Vegas, Desert Chapter monument. Names of military personnel from Southern Nevada who died in World Wars I and II and the Korean War are etched in granite panels.

- The Nevada State Veterans Memorial features a World War I soldier statue among 18 metal-alloy-and-bronze statutes by sculptor Douwe Blumberg. They represent the nation’s war eras from the Revolutionary War to the global war on terrorism. The admission-free memorial plaza is at the Sawyer Building, 555 E. Washington Ave., near Las Vegas Boulevard North, is open 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. seven days a week.

The Nevada State Museum in Springs Preserve, 309 S. Valley View Blvd., has the USS Nevada’s World War I-era bell and ship’s wheel on display. The museum also plans to show a collection of World War I items next year timed to the 100th anniversary of the end of the war on Nov. 11, 1918. The museum is open 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Thursday through Monday. Admission is $9.95 for adults and free to children 17 and under.

A tip of the cap to a veteran father

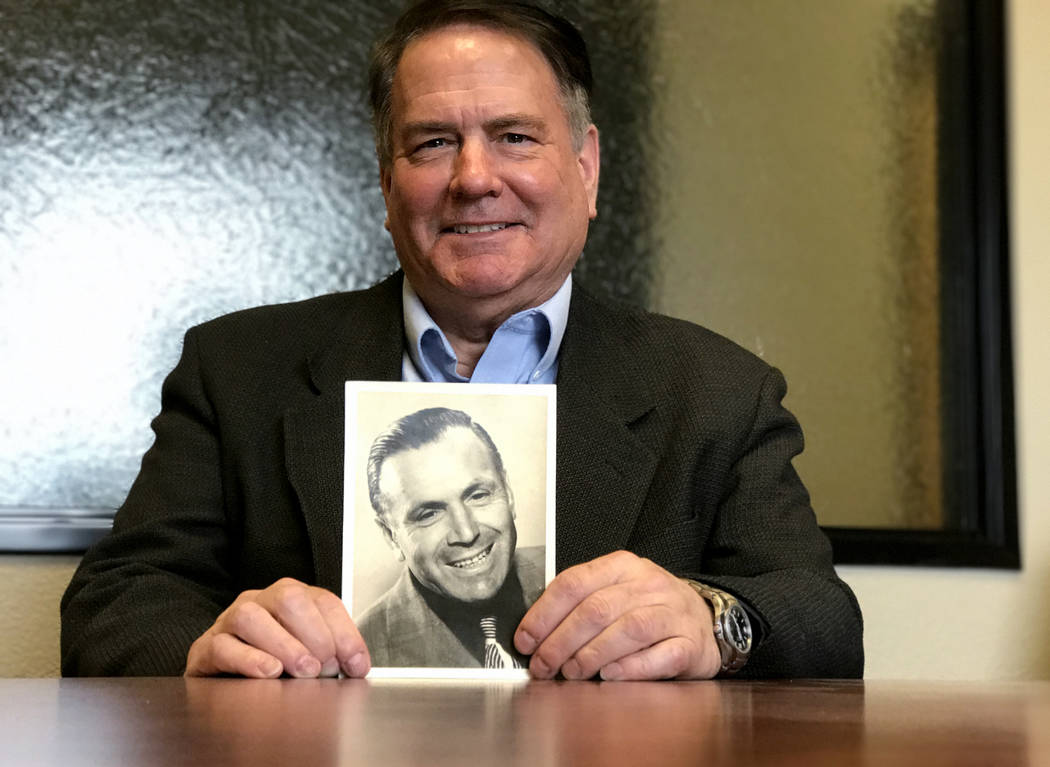

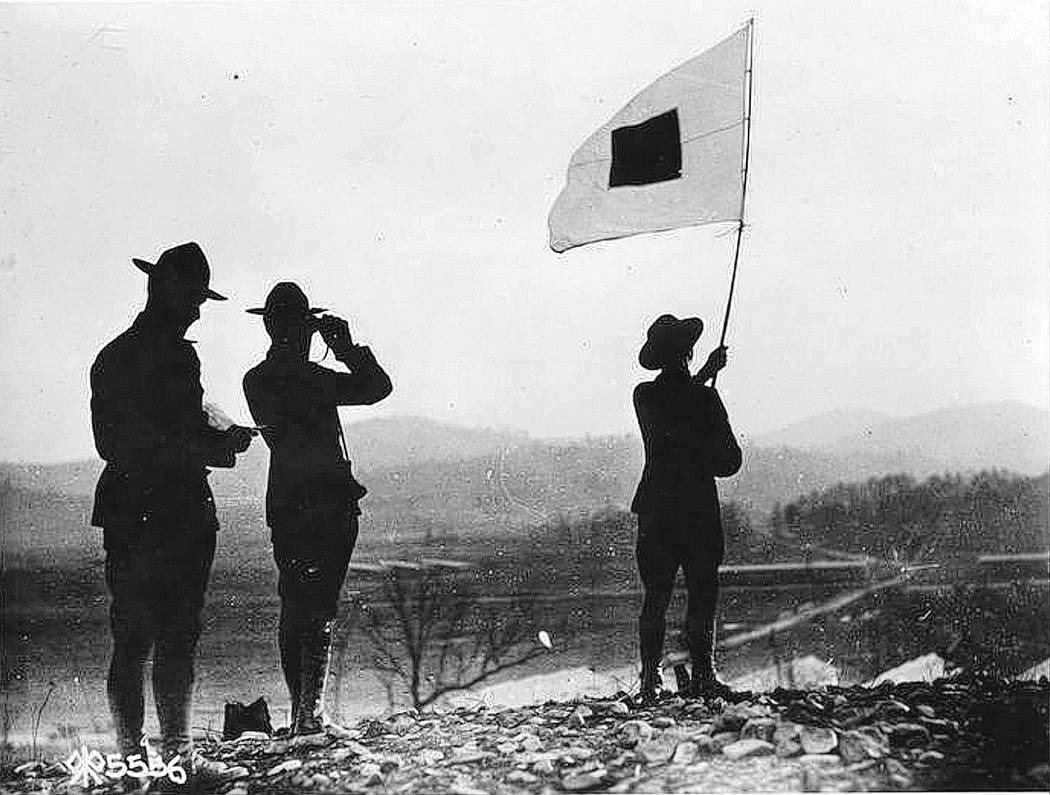

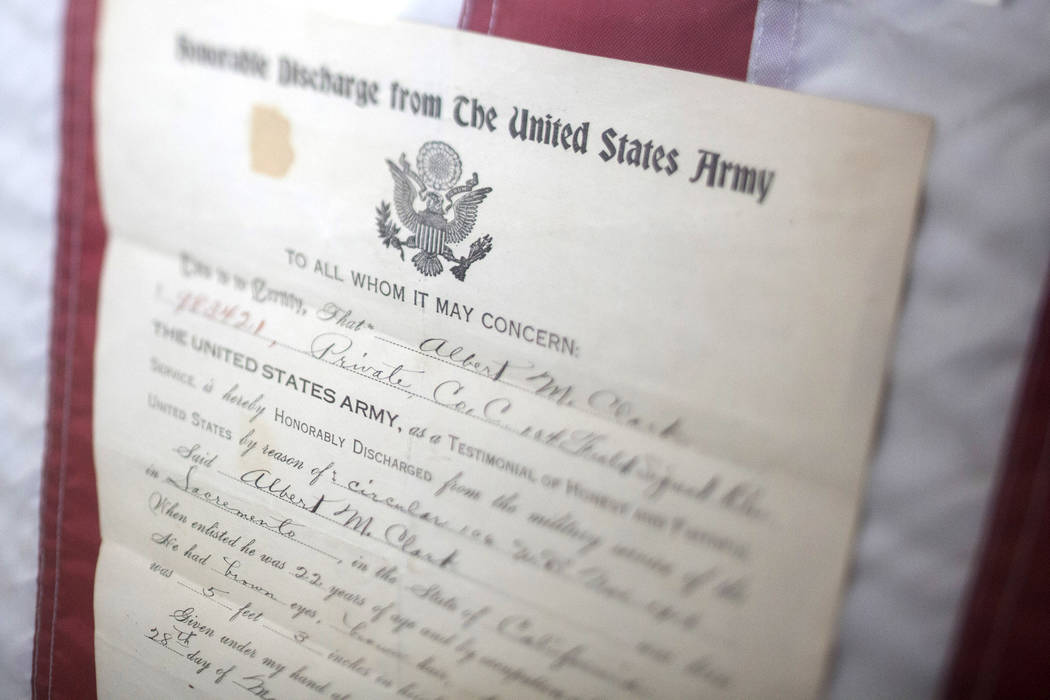

The blue wool cap with “France” sewn in gold letters was worn by U.S. Signal Corps soldier Albert M. Clark, a founding member of the first American Legion post to honor fallen comrades, according to his son, Albert Clark of Las Vegas.

He loaned his father’s cap and discharge paper to the local Post 8 in hopes the American Legion will put them on a nationwide tour.

“It would mean exposure for World War I veterans and anyone who is a son of the American Legion from World War I,” said Clark, who believes he is one of the relatively few remaining sons of World War I veterans in Nevada. His father was born in 1896 but had children late in life, at age 57. He died in 1986.

Clark said his father, like other combat veterans “very rarely mentioned anything about World War I.” That’s why it’s important, he said, to preserve their past and this part of American history.

African-American Medal of Honor recipients

Two African-American soldiers belatedly received the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest valor award, for heroic actions in World War I while fighting with an all-black Army unit.

Two African-American soldiers belatedly received the Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest valor award, for heroic actions in World War I while fighting with an all-black Army unit.

Army Sgt. Henry Johnson, of the 93rd Division’s 369th Infantry Regiment, was awarded the Medal of Honor for “conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life” when he and another soldier on sentry duty were attacked by a German raiding party.

Johnson, pictured here, warded off the attackers in hand-to-hand combat, stabbing one in the head with his knife and forcing more than a dozen to retreat on May 15, 1918, in France’s Argonne Forest, his citation reads.

Cpl. Freddie Stowers, of the 93rd Division’s 371st Infantry Regiment, was awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously for leading his squad during fierce fighting to destroy an enemy machine gun nest in the Champagne Marne sector of France on Sept. 28, 1918.

“While crawling forward and urging his men to continue the attack on a second trench line, he was gravely wounded by machine gun fire,” his citation reads. “Inspired by the heroism and display of bravery of Corporal Stowers, his company continued the attack against incredible odds, contributing to the capture of Hill 188 and causing heavy enemy casualties.”

The Medals of Honor for Stowers and Johnson were presented in 1991 and 2015, respectively, after the Department of the Army reviewed their records.

The Medal of Honor was awarded to 121 World War I veterans — 92 soldiers, 21 sailors and eight Marines.