Old Vegas never grows old at The Bootlegger Bistro

The walls can’t talk. Still, they tell a story.

The lady who started it all with $50 in 1959 narrates.

“These are all people who have been in the restaurant,” Lorraine Hunt-Bono says as she strolls into the bar area of the Bootlegger Bistro, eyeing black-and-gold nameplates akin to rectangular versions of the stars that adorn the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Marilyn Monroe. Elvis Presley. Dean Martin. Sammy Davis Jr.

They all sat in these booths — which still gleam decades later as if their stardom doubled as a protective wax — once upon a time in Las Vegas.

Since 1973, the Bootlegger Bistro has been a local institution, a celebrity hang dating to when platform shoes were all the rage, celebrated for Italian cuisine steeped in generations of know-how. It’s been a Vegas landmark since Vegas was a seventh of its current size.

The Bootlegger was featured on Anthony Bourdain’s “Parts Unknown” TV show, has been named one of the top bars in America by Playboy magazine, and had its stage graced by Rock & Roll Hall of Famer Ruth Brown, Rat Pack running buddy Sonny King, jazz pop great Buddy Greco and countless other musical notables.

“You walk through those doors and you’re immediately hit with a certain level of ambiance,” says Eddie Bowers, a native of Sparks, Nevada, who has been coming to the Bootlegger once or twice a month on business trips since 2017. “You feel like you step into a different world.”

In a city perpetually redefining itself to maintain its status as the entertainment capital of the country, the Bootlegger has remained a sign of the times even as the times have changed, uniting Vegas’ past and its present.

“So many people come in who have never been to Vegas,” says singer and longtime radio show host Dennis Bono, who married Hunt in 2006 “They look at the pictures, they feel the atmosphere, and they go, ‘Ahh, this is the Vegas I heard about: the glory days.’ It really, truly represents the glory days.”

All in the family

If it wasn’t for rheumatic fever and arthritis she might not be here.

Those two maladies, which afflicted Lorraine Hunt-Bono’s father and mother, respectively, brought them to Las Vegas in 1943, seeking refuge from the cold, damp weather of their native Niagara Falls.

Hunt-Bono was 2 years old.

Vegas was a cowboy town back then, the Wild West writ large with neon-enhanced dude ranches such as El Rancho and the Last Frontier checkering the Strip.

Hunt-Bono recalls seeing Frank Sinatra live for the first time as a little girl in this context, the nattily attired Chairman the opposite of a cowpoke.

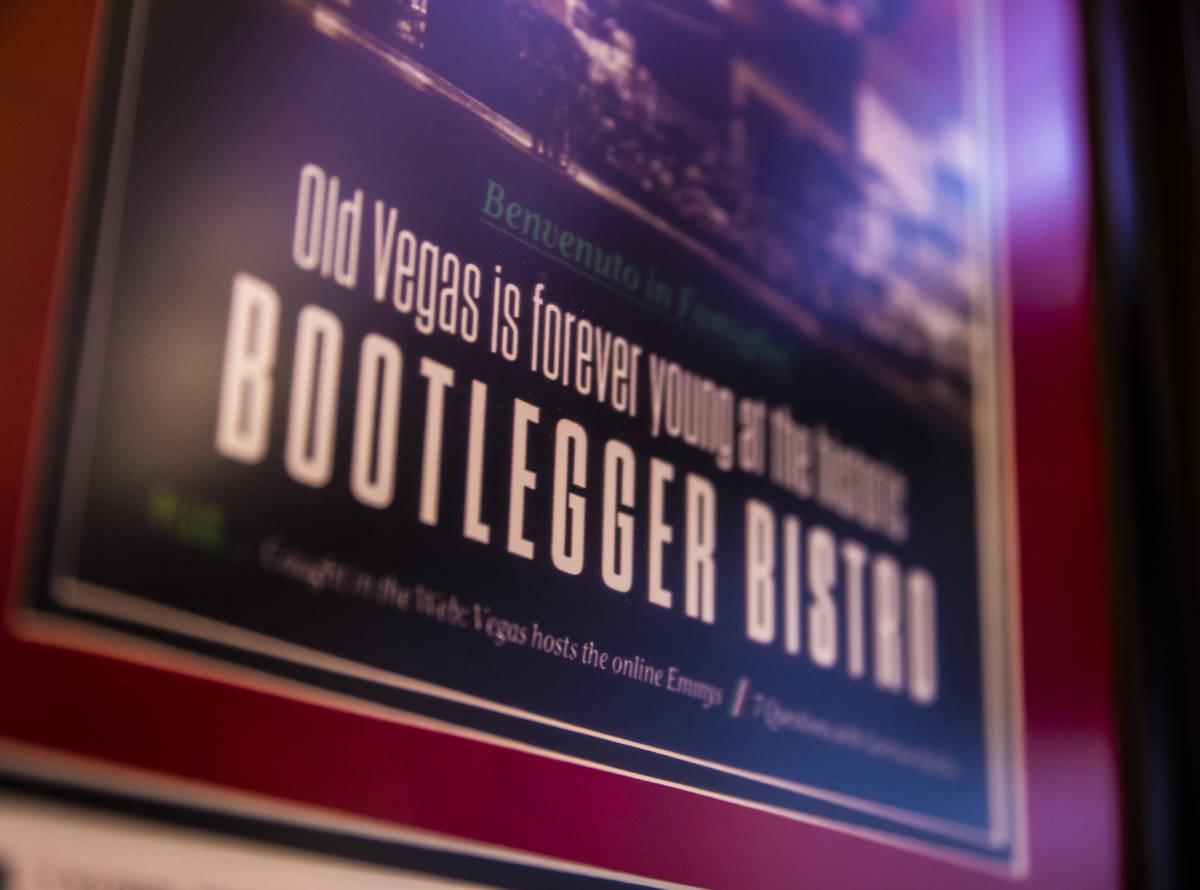

A framed poster promoting Bootlegger Bistro hangs in the lobby of the iconic Italian restaurant on Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2020, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto

A framed poster promoting Bootlegger Bistro hangs in the lobby of the iconic Italian restaurant on Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2020, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto  Bootlegger Bistro on Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2020, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto

Bootlegger Bistro on Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2020, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto “He comes out, and the first I see is these black, patent leather shoes,” she remembers. “And I go, ‘Wow, those aren’t cowboys boots. That’s so cool.’ Then, with the Rat Pack, I was mesmerized: ‘That’s what I want to do. I want to be on that stage, singing with Frank Sinatra.’ ”

Hunt-Bono fancied a career in music at an early age, even though she also was immersed in the family business, which grew steadily, beginning with her parents’ first restaurant, the Venetian Pizzeria on Fremont Street. Al and Maria opened the place with Maria’s sister, Angie, and her husband, Lou Ruvo, in 1955.

In 1966, they all would launch the Venetian Ristorante together on West Sahara Avenue.

Hunt-Bono grew up doing her homework in the back of those places, later enrolling in L.A.’s Westlake College of Music, where she studied piano and orchestration. On summer break after her freshman year, while working as receptionist at Southern Nevada Memorial Hospital for $35 a week, she was invited to try out for the Bobby Page Trio at the Riviera. Page’s female singer was having a baby, and he needed a fill-in.

Hunt-Bono got the gig.

“He says, ‘Oh, by the way, it only pays $125 a week,’ ” Hunt-Bono recalls incredulously of the start of a successful career as a singer. “Oh, my god, I thought I was rich. Immediately, what did I think? ‘I gotta buy some land.’ ”

The Bootlegger is born

In 1959, Lorraine Hunt-Bono put a portion of her first paycheck in show business down on a then-barren, dusty parcel of land at Tropicana and Eastern avenues.

It would lie fallow until 1972.

By then, her father and mother had retired from the restaurant business, though the latter was itching to run a kitchen again.

“I said I’ve got that land,” Hunt-Bono recalls. “How about if we build a little place out there?”

On June 9, 1973, the Bootlegger Bistro opened as part of a shopping center that Hunt-Bono developed. It was named after her great-grandfather Luigi Zoia, an Italian immigrant who sold homemade wine from the boarding house he ran with his wife Maria in Niagara Falls, Canada during the prohibition era.

Located in the spot currently occupied by Putter’s Bar & Grill, the Bootlegger was a hit from opening night.

“The place was just packed,” Hunt-Bono recalls. “My mother’s customers came out of the woodwork when they heard that chef Maria was back. We had a few slot machines, put a piano in there, played a little music, and it was gangbusters.”

The restaurant became especially popular with musicians.

“I became aware of the Bootlegger, ‘Oh, Billy Eckstine used to hang out there’ and these guys,” Bono says of the jazz great. “I was intrigued by the artists that I respected and found out that this was one of the places they hung out. I gravitated to it.”

He wasn’t alone: The Bootlegger was a place to see and be seen.

“It always felt like you were doing something naughty by going there, because those were the days when the mob was still around,” says Marilyn Larson, a Bootlegger regular who began going to the restaurant with her late husband, hotel executive Mel Larson, in the mid-’70s. “It had that kind of an atmosphere and an ambiance. It was fun, and it was gorgeous.”

Eventually putting her music career aside to run her restaurant, Hunt-Bono later would get into politics, becoming a Clark County commissioner in 1994, and lieutenant governor of Nevada five years after that.

In 2000, she decided to sell the shopping center that housed the Bootlegger.

“We had a good run there,” she says, “but the neighborhoods were changing, and we always wanted to be on the Strip. We just could never afford it.”

Back in 1983, she and her father had bought another barren plot of land, this time on South Las Vegas Boulevard. Seventeen years later, it was time to develop it.

The Bootlegger is reborn

Pointing to the exposed brick walls, the broad arches, the sepia-toned photos of relatives from a distant past, she uncorks the history of the room like a sommelier of memories.

“I brought all this stuff from the old Bootlegger and said to the kids, ‘Don’t touch it,’ ” Hunt-Bono recalls, while tucked into a booth in the dining room of the current incarnation. “ ‘Don’t touch the colors because this is the Bootlegger.’ ”

Hunt-Bono tells the story of the Bootlegger like a parent detailing some magnificent adventure to a child at bedtime: her voice rapt, her hands as active as a maestro’s while conducting an orchestra.

Twenty years ago, Hunt-Bono broke ground on the 5 acres of land that would become the contemporary version of the restaurant, which opened in 2001.

While the decor largely remained the same in the new, larger version of the Bootlegger, the spot would evolve into a 24-hour, seven-day-a-week enterprise.

Photos of family, friends and famous guests are displayed throughout Bootlegger Bistro on Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2020, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto

Photos of family, friends and famous guests are displayed throughout Bootlegger Bistro on Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2020, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto  A print of Las Vegas icon Frank Sinatra, a frequenter of Bootlegger Bistro, hangs in the dinning room on Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2020, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto

A print of Las Vegas icon Frank Sinatra, a frequenter of Bootlegger Bistro, hangs in the dinning room on Wednesday, Aug. 5, 2020, in Las Vegas. (Benjamin Hager/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @benjaminhphoto “It was the place to go hang,” Bono recalls. “Sonny King used to start at like midnight or 11 o’clock and go till 2, 3, 4 in the morning, and all the restaurant people, all the entertainers, after their shows, would come to the Bootlegger. It’s where people really have a chance to see some of these legends and the camaraderie between all of them, not just musically, but personally.

“It was very contagious,” he continues, “The next thing you know, rock ’n’ rollers are coming in because it developed this legendary image.”

Credit the cultivation of the latter clientele to Hunt-Bono’s son Ron Mancuso, a professional guitar player and music producer who runs a studio next door to the Bootlegger.

He officially joined the staff in 2003, as chief operating officer, his son Roman came aboard three years later, adding a fourth generation to the family business.

Mancuso notes how the Bootlegger continues to serve as connective tissue between the Las Vegas of yesterday and today.

“There’s so few businesses that really were from old Vegas and have that vibe,” Mancuso says. “People want that. I think it’s comforting to go back to some place that you’ve been to for many years or that other people have talked to you about for many years, and it’s still the same. We’ve been a part of the fabric of the community for a long, long time.”

This is underscored when Hunt-Bono leads a tour of the dozens of photos that line the Bootlegger’s walls, from black-and-white photos of Dean Martin to color shots of a humble-looking Fremont Pizzeria.

“Today you couldn’t run a place like that,” she says, while gazing upon the latter. “Eight-hundred dollars was all they had to open this little restaurant.”

Eventually, she comes upon a photograph of the Landmark, owned by Howard Hughes, which Hunt-Bono opened in 1969 with her group, the Lauri Perry Four.

Twenty-six years later, as Clark County commissioner, she pushed the button to detonate it.

It’s yet another example of how things come and go in this town.

Just not the Bootlegger Bistro.

“We implode things that we shouldn’t implode, in my opinion,” Hunt-Bono says.

“Some of it,” she notes with a measure of finality, “you should keep.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter and @jbracelin76 on Instagram

The Bootlegger's namesake

It all began with picnic tables in a living room, close to 100 years ago.

In the early 1900s, Lorraine Hunt-Bono's great-grandparents Luigi and Maria Zola migrated to Niagara Falls, Ontario, from their native Italy. They opened a boarding house largely populated by factory workers employed on the American side of the border.

A native of Venice, Maria gained local acclaim as a great cook. The boarders soon began asking to bring their friends over to feast.

They offered to pay.

Prohibition was still in effect in the U.S., but Luigi made wine and whiskey in his basement. He became known as the Bootlegger.

With Maria's eats and Luigi's spirits, a business was born.

Their living room became a dining room on the weekends.

Luigi and Maria's granddaughter Maria, who had been sent to live with them when she was 9, began taking reservations, planning meals and hauling her little red wagon to the nearby farmers market once a week to stock up on supplies.

Growing up in this environment, Maria learned how to run a business from the ground up and became quite a cook. "Her art was cooking. She was like a jazz musician," Hunt-Bono says.

In 1936, at age 19, Maria wed Albert Perry. They had a daughter named Lorraine.

The dry, desert heat soon would beckon.