War experience vivid for former POW

“Forty-something years is a long time to carry a resentment. That’s why I’m doing this.”

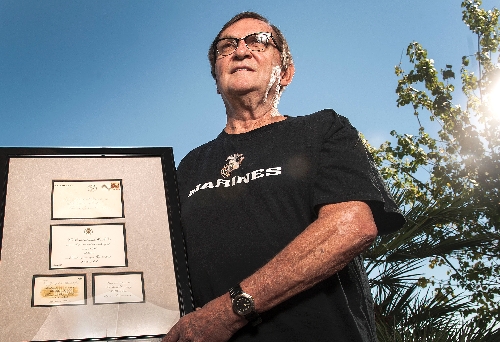

Former prisoner of war Joe North made the observation before he presented a wreath Friday at Nellis Air Force Base’s Freedom Park to honor POWs and those who went missing in action.

“Remember, we still have thousands of men and women in harm’s way, and we need to bring them home safely and responsibly,” the Marine veteran from Las Vegas told friends about his role in the National POW-MIA Recognition Day ceremony.

For 47 years North has said little about his POW experience. And, like that experience, it took courage for him to participate in the ceremony as he stood shoulder-to-shoulder with three other ex-POWs: Dean Whitaker and Jack Leaming from World War II and Gene Ramos from the Korean War. After they presented a wreath to recognize fallen and missing comrades, seven airmen fired three rounds each.

North, 67, said he was “fine until they fired off those three rounds. The report of firearms just jolts me. The last thing I heard was a bunch of rounds like that before one went through my thigh.

“Courage,” he said, paraphrasing author Ernest Hemingway, “is the ability to maintain grace under pressure.”

Grace defines this reserved, bespectacled man – an athlete, piano player and history student who was allowed to join the Marines at age 17 with his parents’ reluctant permission. He wanted a challenge and “needed some more discipline in my life. And boy did I get it.”

He grew up in Denver, the adopted son of well-to-do parents in their 50s. Their urging that he play the piano helped him land a spot in the Marine Corps’ radio and telegraph school.

“I was real quick on the telegraph key,” he said, which is why he was selected to be “a half-assed trained Recon Marine, enough to know what to do and tough it out” when it came to calling in airstrikes and artillery barrages.

“Three other guys and I had these high security clearances, and they asked us to man the teletype in the secret, secret bowels of hell at Camp Smith in Hawaii,” he recalled.

“I remember watching the teletype spit out this yellow sheet. Generals and State Department people were writing these paragraphs that were way over my head,” he said.

“But one thing kept popping out, the word, ‘Vietnam.’ I turned to the guy on my right and said, ‘What in the (expletive) is a Vietnam? And that was the kickoff to the start of the game.”

Soon after that, he received orders for escape-and-evasion training in Okinawa, Japan. “I wondered, ‘Why escape? Escape from what?’ ” he said.

Assigned to Headquarters Company of the 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines, they were the first combat Marines to land at Da Nang Air Base in the spring of 1965. He was assigned to operate radios at the Hill 327 command center for Gen. Lewis Walt.

He wasn’t there for long. His next stop, which turned out to be his last, was with Lima Company at Hill 22, about 100 miles south, where a radio operator with special clearance was needed to direct airstrikes.

Their primary weapon of defense was a tank parked on a hilltop and surrounded by sandbags. Instead of his M-16, he carried a sawed-off shotgun because, he was told, he would only have to fire at close range.

“We were going out on patrols every night. They called us fire teams, and those of us who had to go farther were called kill teams because we were going into (the Viet Cong’s) part of the woods,” he said.

Snipers routinely fired on Lima Company. Sometimes the enemy set booby traps by hanging grenades from the perimeter wire where fire teams would exit.

“I was never afraid of dying or being hurt. I had grown up with no fear,” he said.

One night, enemy combatants took out two Marines from his four-man fire team, leaving him and a gunner to fend for themselves until they ran out of ammunition.

“That was the first time we saw the red star on their helmets,” he said, describing the helpless feeling of being captured. “They took us and put us away in little bamboo shelters, prisons that were bound tight.”

Often they would be “whacked around, but I would show no pain. I would not give them the satisfaction.”

Eventually, the enemy soldiers separated the two POWs. They made North hike to a mountain location where they continued to torture him.

“I understood Vietnamese, so I knew when I was going to get a licking,” he said.

He said he can’t remember how many weeks he was held captive in the later months of 1965, but it was “long enough.”

“All I could think of was how in the hell I’m going to get out of here. Escape and evasion, all the things they taught me I was trying to pull off. I never gave up,” he said.

Back home in Denver, Marines showed up at his parents’ front porch, handed them a folded flag and told them he was missing in action and presumed dead.

“They kind of jumped the gun,” North said. “It was the early part of the war, and a lot of people didn’t know what they were doing.”

While in his bamboo pen he heard enemy soldiers running up the mountain, yelling and screaming. They had been smoking a narcotic and planning to attack Da Nang Air Base with satchel charges.

Despite the enemy’s drug use in combat, “in 1965 we didn’t have access to, nor did we have drugs. That came after Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and protesting in ’67,” North recalled.

“They were smoking this stuff and getting wilder and wilder, and talking about taking that air base. I wasn’t blindfolded, so I could see they had big bags and were going to drop satchel charges. Then all of a sudden everybody was gone. The rain had washed away all the things holding my little jail together. So I lifted up the bamboo and pulled myself out.”

On a moonlit night, he ran through sugar cane. “I didn’t hear anyone behind me for quite some time. Then all of a sudden I saw some lights. The moon went away, and I got off the trail and hid behind a tree.”

During the night he heard, “whoosh, whoosh, whoosh” followed by the sound of something that plunked in the mud. When daylight came he looked over and saw a Chinese hand grenade. “It was a dud. I said, ‘Boy am I a lucky bastard.’ ”

Peering from the hillside, he could see a road and water off in the distance.

“I knew that was Da Nang Bay. I’m out of here. I started running. Then, about halfway there, I heard a couple reports from an AK-47 rifle. I was hit,” he said. “The lucky son of a bitch got me in the back of my right thigh, and the bullet went straight through. I kept on running.”

When he reached the highway, he waved down civilians, shouting “bach si,” the Vietnamese word for “doctor.” As luck would have it, a guy in a back seat was a doctor, who grabbed a medical pack and gave him a shot of morphine.

The next thing he remembers is being cared for by a medical company at Da Nang Bay. Eventually he was flown to Okinawa “to get patched up,” then returned to Marine units in Vietnam and given a lie detector test “to see if I had spilled my guts, and I passed.”

After a stint in the United States, handing out clothes in Easy Company at Camp Pendleton, Calif., to Marines getting deployed, he was honorably discharged in March 1967, bitter about the war and the way it ended for him.

“They didn’t know what to do with me,” he said. “They put me back in country, gave me lie detector tests. … I said that’s enough.”

Six years later while living in Hawaii, his parents in Denver received a letter for him from the White House.

“The President and Mrs. Nixon request the pleasure of the company of Mr. North at dinner on Thursday evening, May 24, 1973 at 7 o’clock,” reads the ex-POW reception announcement.

He didn’t want to go.

“I RSVP’ed in somewhat negative fashion to the president of the United States, and it was not well-received,” he said. “Why in the hell are you contacting me now? Don’t bother me anymore.”

His response drew attention from investigators, “wondering if I was a subversive.”

“I don’t want to sound like sour apples,” he said. “I love the Marine Corps.”

His advice to today’s young soldiers and Marines: “Number one, pray for peace. Number two, If you must go to war, fight valiantly and return whole.”

Contact reporter Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308.