Civil drones: Tools of peace tested near tools of war

They can be used for war. And they can be used for peace.

Ironically, when the state of Nevada set out to demonstrate its civil uses for drones as one of the six FAA-approved test beds for merging the budding industry into the national airspace, it chose a secure swath of high desert where the nation’s nuclear bombs were tested during the Cold War.

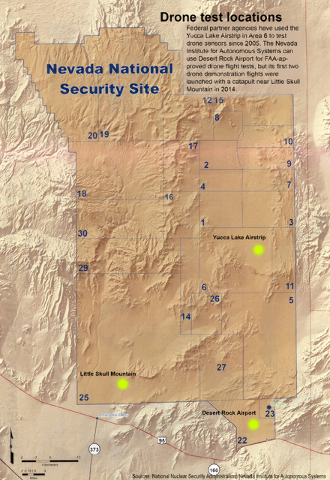

A 7,500-foot runway at Desert Rock Airport at the federal Nevada National Security Site, 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas, had been designated for the state’s program to test drones for such uses as surveilling forest fires, assessing flood and earthquake damage, checking power lines and delivering medicine to people in remote areas.

Desert Rock had been used during the 1950s for staging troops to observe above-ground nuclear bomb explosions. Later, after full-scale nuclear weapons tests were restricted to below ground, Desert Rock Airport was used to fly in scientists from the national laboratories in Northern California and New Mexico.

But the contractor for the state’s nonprofit institute had another place at the security site in mind because the company testing its drone didn’t require a runway.

In the late spring of 2014, the Nevada Institute for Autonomous Systems facilitated two test flights of The Boeing Co.’s remotely piloted aircraft similar to its 10-foot-wingspan ScanEagle.

Technicians from the aircraft industry giant used a hydraulic catapult to fling the drone into the security site’s restricted airspace.

Sources familiar with the project confirmed the Boeing test flights occurred.

Don Cunningham, a former Nellis Air Force Base pilot and safety officer who was program manager for the Nevada Institute for Autonomous Systems — the state’s nonprofit drone test flight facilitator — said test flights for a “developmental, catapult-launched system” were conducted by “a major aerospace manufacturer” in an area used for an old MX missile project near Little Skull Mountain. The location is about 25 miles southwest of the federal government’s little-known runway in Area 6.

Although the Area 6 facility had been built in 2005 for drone use by federal agencies complete with a 5,000-foot runway, hangar with clamshell doors and a ground-control building, Cunningham was unaware of this Yucca Lake Airstrip until the Review-Journal published a story about it March 6.

“I was going, ‘wow.’ It makes sense. To me it’s a perfect spot,” he said Thursday about the Area 6 runway.

“It was really a well-kept secret as are a lot of things out there,” he said.

But Cunningham said the first Boeing demonstration flight for its small surveillance drones didn’t need an elaborate ground-control station or runway to take off and land. Instead the launch catapult was hauled to the demonstration site. After the drone had completed its flight, operators steered it by remote control for a safe capture in a net.

BUDDING INDUSTRY BLOSSOMS

The state’s test flight schedule remained relatively dormant during Cunningham’s tenure until the institute reorganized in 2015.

The nonprofit institute, sponsored by the Governor’s Office of Economic Development, has conducted 170 test flights of drone “smalls” since September at various locations, including near Mesquite, Hawthorne and Reno-Stead Airport. Upcoming tests with “bigs” by defense contractors are on the horizon, said the institute’s Director of Technical Operations Chris Walach.

“Desert Rock might have restricted airspace but that doesn’t mean we’ve avoided using it,” Wallach said March 14 at the institute’s office in downtown Las Vegas. “It’s driven by demand.”

Flight tests of drones that weigh 55 pounds or less only require airspace that’s 400 feet above ground. The fee for restricted airspace of up to 10,000 feet for bigger drones weighing up to 500 pounds can be too costly for small companies, approaching $10,000 a day. Arranging to use restricted airspace, say at a military installation, presents another hurdle in that reservations must be made months in advance.

For example, partners such as the state’s institute that want to use the security site’s restricted airspace at Desert Rock can do so under a full cost recovery condition. It requires the security site’s operator, the Department of Energy, to be compensated for all expenses and services including electricity, site maintenance, safety support and any improvements that are made. This is done so there is no burden on taxpayers for a partner’s private endeavor.

Mark Barker, director of business development at the Nevada Institute for Autonomous Systems, said there are about 30 ranges in Nevada where companies can conduct drone test flights with a certificate of authorization from the Federal Aviation Administration.

“We’ve got many places to fly. What we need is people to fly in them,” he said.

According to FAA Administrator Michael Huerta, there are plenty of potential drone operators waiting in the wings of private enterprise. At a conference in Austin, Texas, this month he said there are more than 400,000 registrants in the federal drone registry.

Among the issues that need to be addressed before they share the skies is a looming safety concern. There were more than 1,000 complaints in 2015 from aircraft pilots and others about interference from drones when manned planes were landing.

FOR DEFENSE, DOMESTIC USE

When asked if drones such as an Air Force Predator could have been used to monitor the 2014 standoff near Bunkerville between government agents and militia supporters of defiant rancher Cliven Bundy, Cunningham said that would be unnecessary.

“For that you wouldn’t need a military grade UAS (unmanned aerial system). I could have done that with an octacopter,” he said, referring to a small, remote-controlled surveillance helicopter.

A 2015 Defense Department inspector general’s report obtained through the Freedom of Information Act by the Federation of American Scientists indicates the office of Secretary of Defense “interim guidance” for military drone support at the request of civil authorities lacked details.

“It does not provide a mechanism for how to process that request,” states the IG report, followed by a a half-page of redacted sentences.

However, on Feb. 17, 2015, about a month before the IG report was published, a deputy secretary of Defense policy memo titled “Guidance for the Domestic Use of Unmanned Aircraft Systems,” rescinded the “interim guidance” that had been followed since Sept. 28, 2006.

During that nine-year period, “less than twenty events” were listed as military drone support for domestic civil authorities, according to the IG report.

Asked about this, a spokesman for the office of the secretary of Defense said “none of them were for surveillance of ‘subjects.’”

“We’ve done search and rescue missions. Mostly they have been used for damage assessment” of floods and fires, the spokesman, Air Force Lt. Col. Thomas Crosson, wrote in an email last week.

“We’ve used them for ‘real world’ as well as for training. All of the missions were flown at the request of state officials” such as governors and emergency management officials, Crosson said.

The current Defense Department guidance memo expires Feb. 17, 2018. It stipulates that armed U.S. military unmanned aerial systems such as MQ-1B Predators and MQ-9 Reapers that can shoot laser-guided Hellfire missiles “may not be used in the United States for other than training, exercise and testing purposes.”

The memo says “the only exception” to the requirement for the secretary of Defense to approve military drone use for domestic operations “are search and rescue missions involving distress and potential loss of life that are coordinated by designated rescue centers.”

To alleviate fears of spying on citizens, the memo says the Department of Defense will promote development of policies that “ensure that DoD UAS are able to operate safely with the national airspace while also balancing and protecting personal privacy.”

Steven Aftergood, director of the Federation of American Scientists Project on Government Secrecy, said questions remain about the Pentagon’s domestic drone use policy in regard to homeland security and potential foreign or domestic terrorists.

“These are good questions that I’m not sure have been fully worked out,” he said.

“With the technology out there, there is going to be a temptation to use it,” Aftergood said.

Contact Keith Rogers at krogers@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0308. Find him on Twitter: @KeithRogers2