Remains of three Civil War veterans, Las Vegas pioneers find final home

After nearly 20 years of efforts by their descendants and others, three Civil War veterans who would emerge as early pioneers in Southern Nevada were honored on Veterans Day at their final resting place on land they once owned at what’s now Kiel Ranch Historic Park in North Las Vegas.

Around 50 people attended the dedication of a large brown and black marble mausoleum housing four metal coffins with the skeletal remains of Conrad Kiel, his sons, Edwin and William, and Kiel family friend Mary Latimer. The remains of an unnamed infant were interned with Edwin, believed to be the baby’s father.

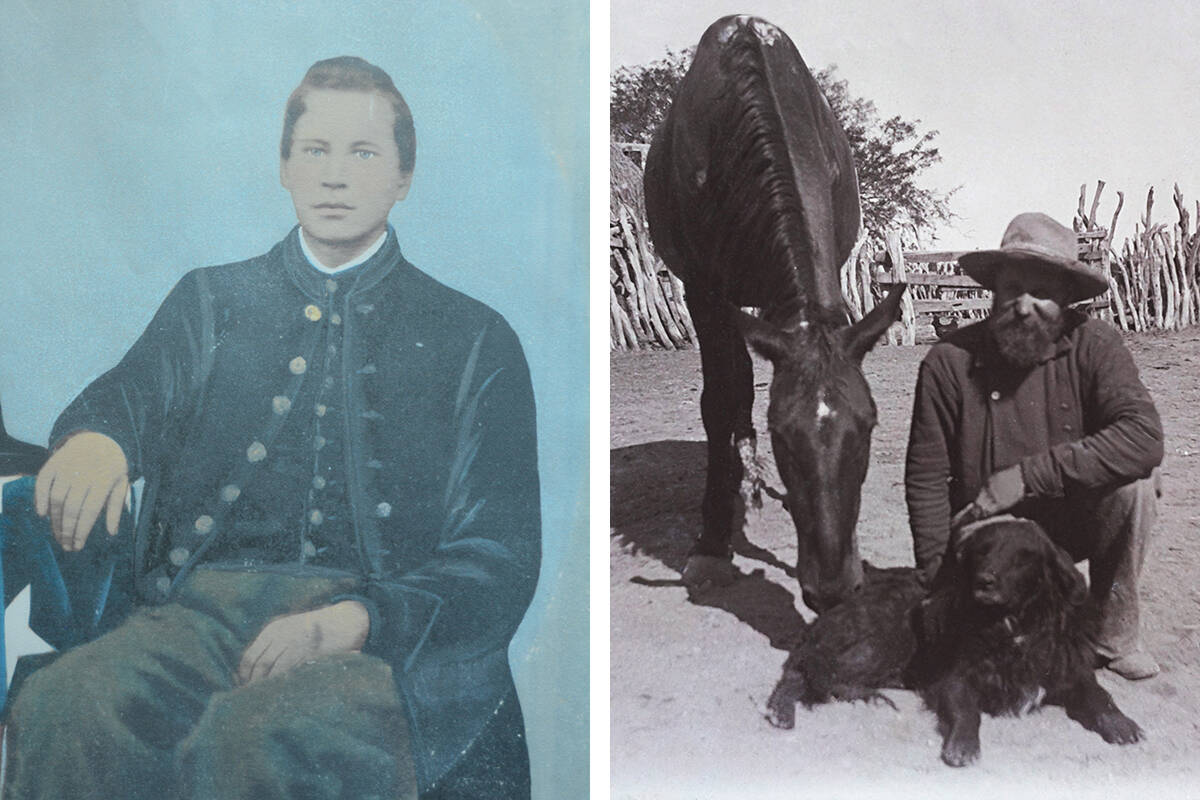

Conrad served with a Pennsylvania regiment of the Army of the Potomac, while Edwin and William mustered out of Ohio units for the Union.

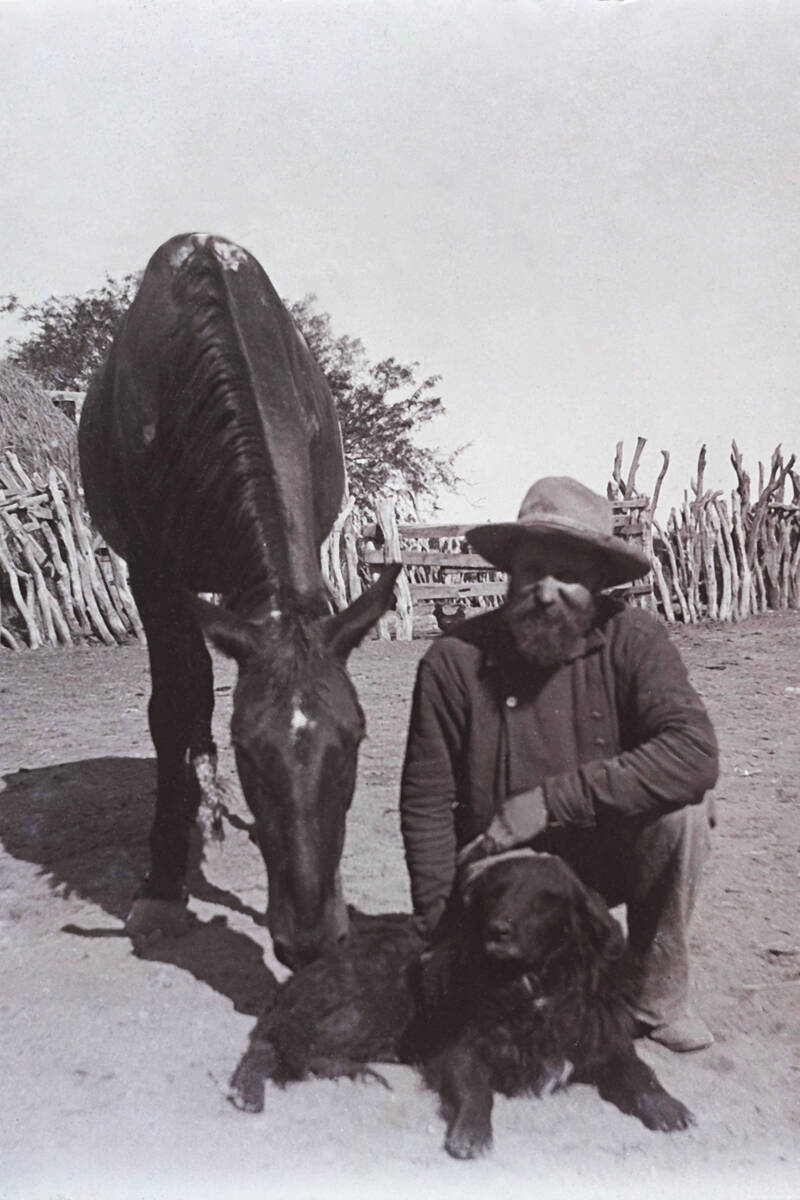

But those with appreciation for local history know them as the Kiel family, whose property served as one of only two ranches in the nearly deserted Las Vegas Valley in the late 19th century and would lead to the creation of the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad and the town of Las Vegas.

The bones and skulls of all five people had been kept in storage as specimens at UNLV’s Anthropology Department from 1975 to 2019 before the university finally acceded to the wishes of family members, local historians and Mayor John Lee to have them transferred to what’s left of the Kiel’s’ once-sprawling farm that included a general store for travelers on the Old Spanish Trail.

The remains were originally buried at a small cemetery on the Kiel Ranch. Graves for Conrad and Mary were filled after they died — Mary in 1884 and Conrad in 1894. William, Edwin and the baby were buried in 1900.

‘Back in the land where they were originally buried’

The graves stayed after the Kiel heirs sold the land in 1901 to a railroad that merged in 1903 with the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad operated by U.S. Sen. William Clark and his brother J. Ross Clark.

Colleen Herbst, 59, a Kansas City, Kansas, resident who is Conrad’s great-great grandniece, said she was surprised to learn about the storage of her ancestors’ bones during a search of her family tree in about 2003.

“We’re very pleased just to have them back in the land where they were originally buried,” Herbst said at the ceremony. “This is perfect.”

“It was very disrespectful,” said Pat Reisbeck, 85, a Denver-area resident and the great-great-granddaughter of Conrad’s brother John, also a Union veteran. “We thought it was outrageous. We thought they were reburied.”

During the event, Air Force ROTC cadets from Rancho High School draped American and Nevada state flags over the mausoleum. A trumpeter played the national anthem. A cadet color guard marched through the crowd.

Five men from the Southern Nevada Living History Association, dressed in Union Army outfits, fired volleys from replica Civil War rifles. Two women dressed in 19th century-style full skirt dresses. The trumpeter then played taps. The cadets folded the flags and gave one each to Herbst and Reisbeck.

A long time coming

Joe Thomson, a Las Vegas historian who organized the ceremony and helped run the effort to transfer the remains, said that local businesses donated the metal coffins and the bricks, cement, marble and labor to build the mausoleum.

Other donors provided clothing placed with the remains, including western boots and cowboy hats for the men and a pioneer period-type dress for Latimer’s remains.

Thomson said that Mayor Lee, North Las Vegas City officials, Herbst and Reisbeck, Corinne Escobar of the Preservation Association of Clark County and UNLV’s Anthropology Department, among others, worked together to get the remains to the park site.

The bones, clothing and coffins were finally interred in December 2019. A ceremony was planned for 2020 but had to be delayed because of the COVID pandemic, he said.

Study of bones leads to decades of storage at UNLV

Thomson said he first heard about the storage of the bones at UNLV while a taking an anthropology course as a graduate student of history there in 2000. He asked a professor to show him the remains.

“I thought it was disgusting,” said Thomson, who decided then to see if there was a way to return them to the ranch site.

The Anthropology Department arranged to have graves containing the bones of the four adults and child dug up in 1975 for a study to determine what caused the deaths of Edwin and William.

The coroner in 1900, then based far away in Pioche, ruled that Edwin had shot William and then himself in a murder-suicide.

Investigations done in 1975 and 2011, involving police, dentists, forensic and other specialists, concluded that both men had been murdered by one or more persons. No one was ever arrested in the case.

A spokesperson for the Anthropology Department did not return a call for a comment.

The 7-acre Kiel park, with an adobe dwelling built in about 1895 and since renovated, is about all that is left of the Kiel family’s 240-acre farm.

It once grew citrus fruits, apples, hay and grapes, thanks to its artesian spring, which still flows today.

Thomson said that the correct pronunciation of Kiel is “keel,” and that the family name has been misspelled as “Kyle.”

Conrad Kiel once owned a sawmill outside his ranch that used trees cut from the Mount Charleston area, and that is how Kyle Canyon got its name, he said.

This story has been updated to correct the year of Mary Latimer’s death, which was in 1884, and a misstatement of the school attended by Air Force ROTC cadets who draped flags over the mausoleum at Kiel Ranch Historic Park. The cadets attend Rancho High School.

Contact Jeff Burbank at jburbank@reviewjournal.com. Follow him at @JeffBurbank2 on Twitter.