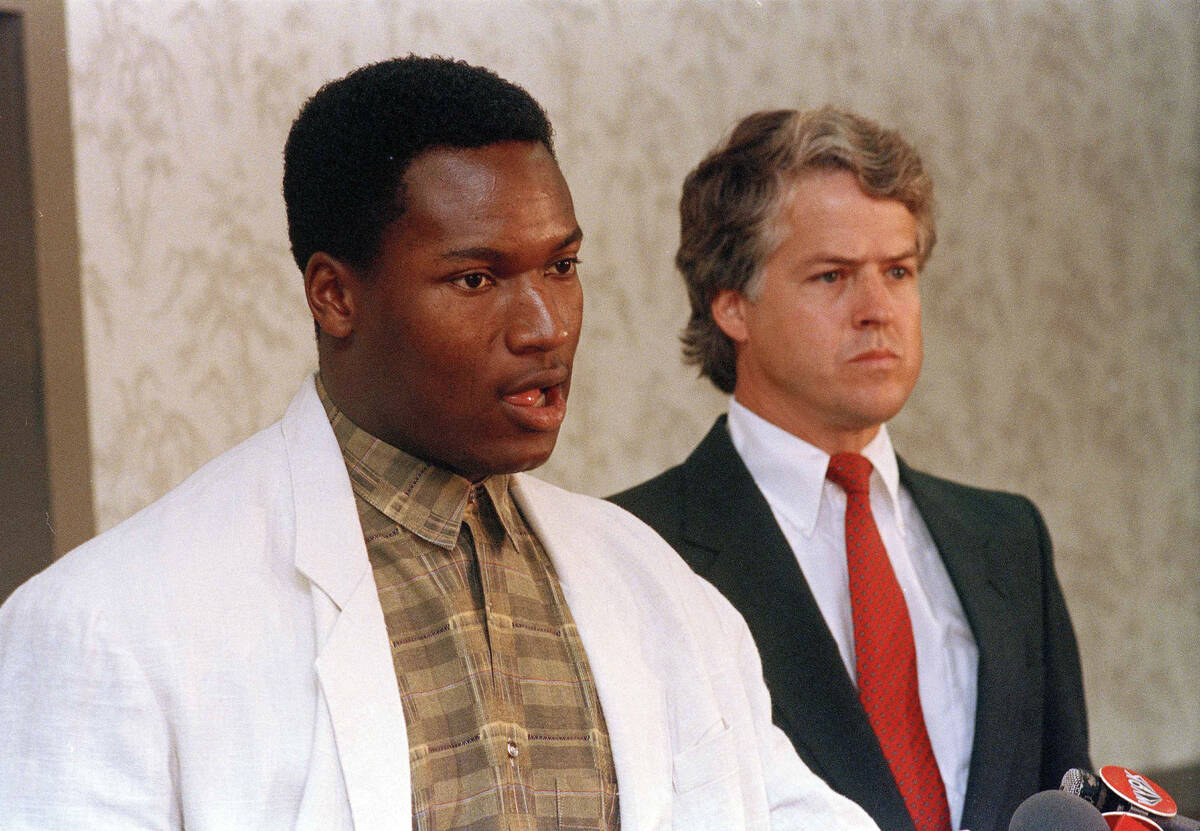

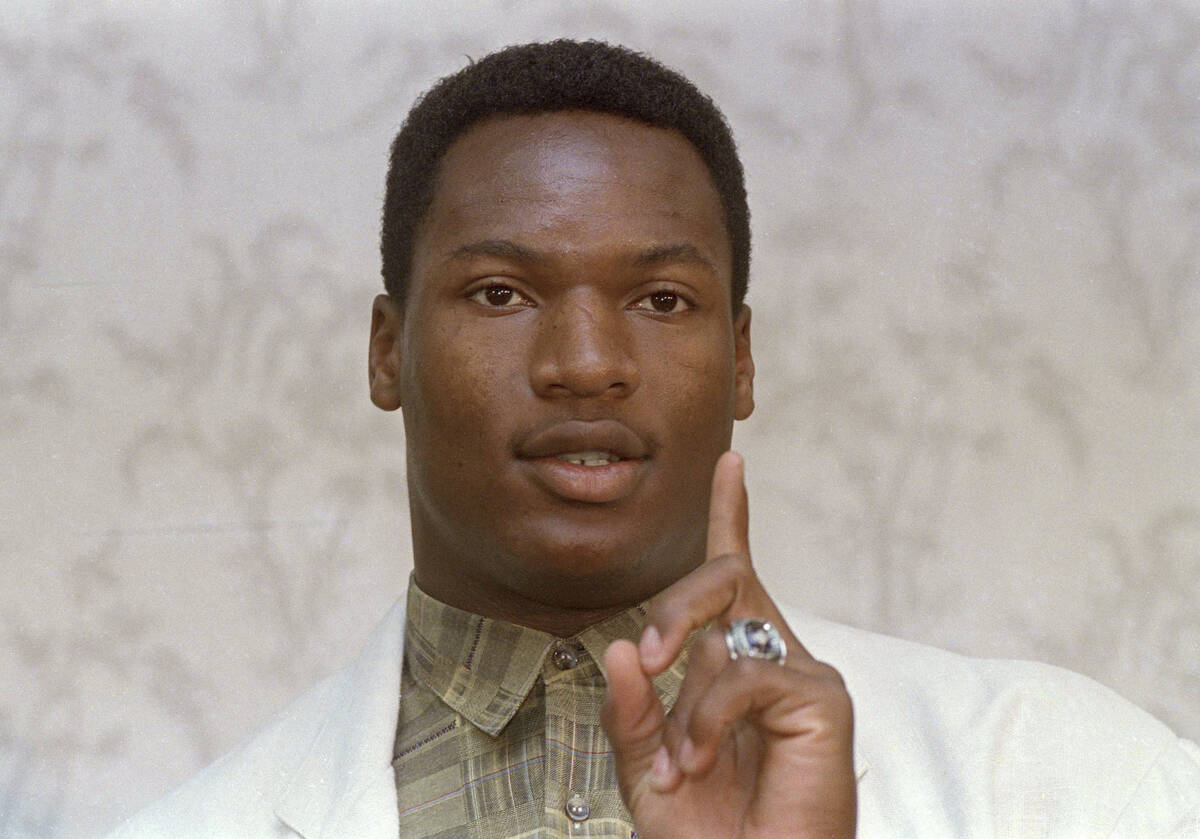

‘The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson’

“The Last Folk Hero: The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson,” is Jeff Pearlman’s 10th book.

He interviewed 720 people over the span of two years, and spent time roaming Bessemer, Alabama, and Auburn, Alabama, seeking out the secret that is Bo. It is available for order here: https://www.amazon.com/

Here’s an excerpt:

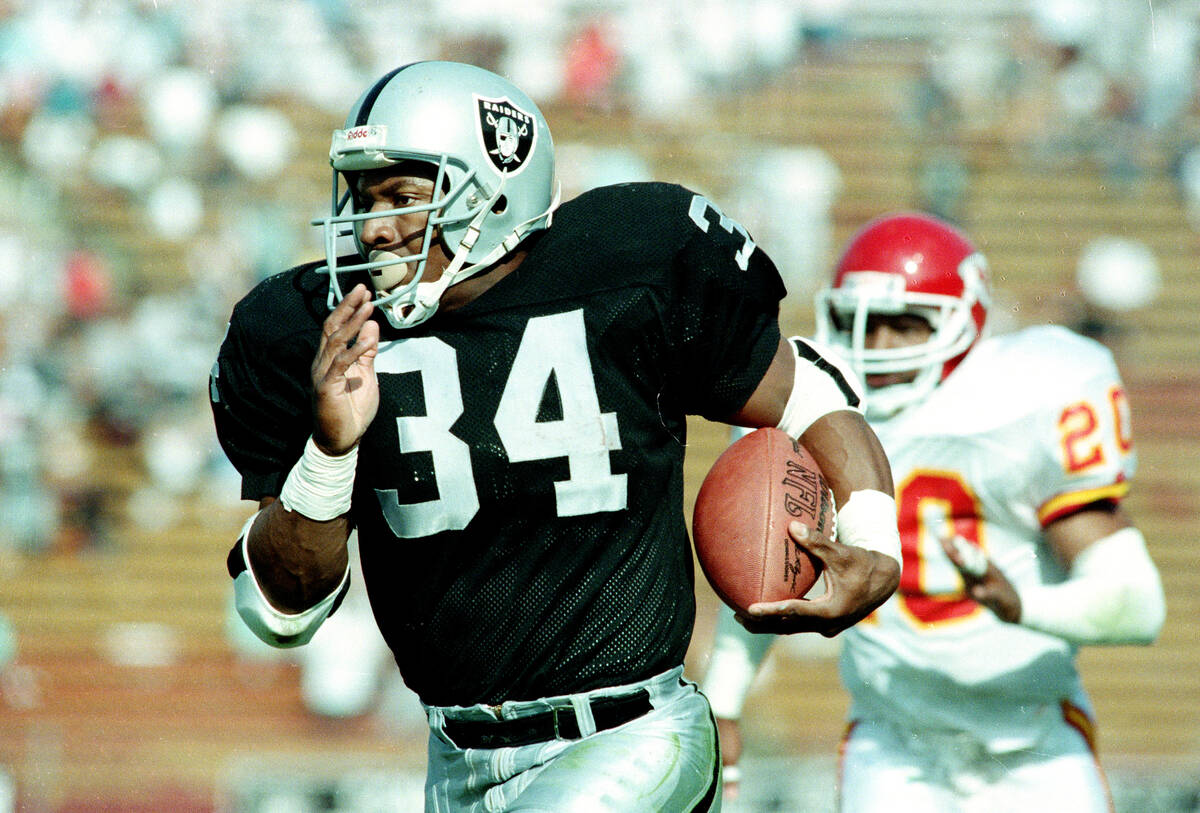

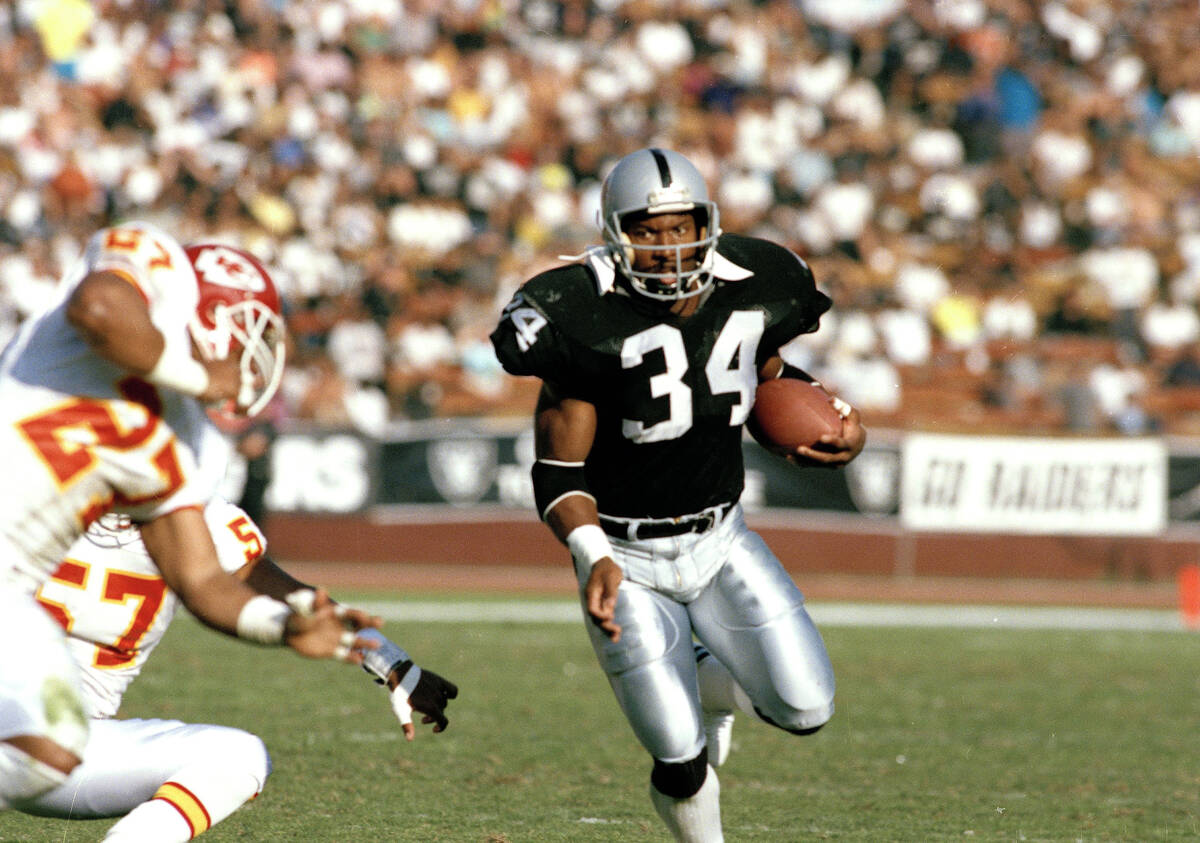

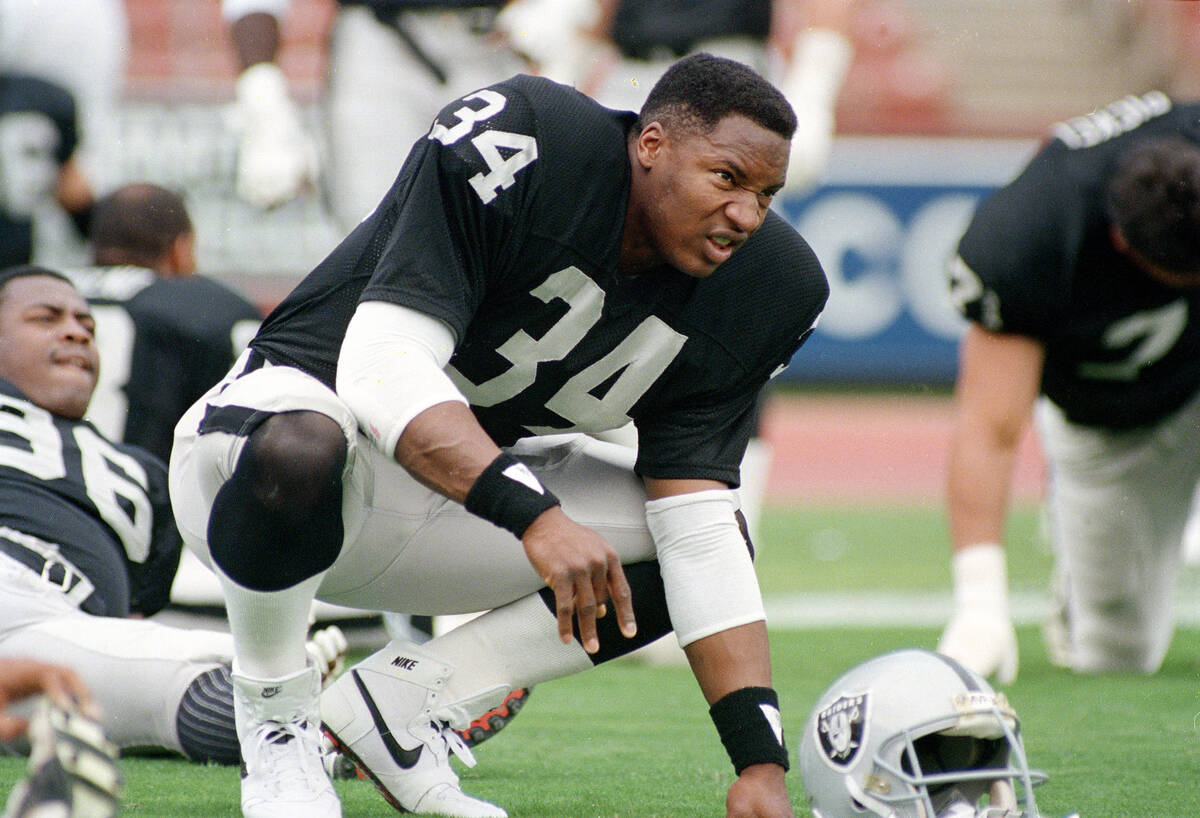

In the final weeks of the 1990 NFL season, Bo Jackson (who ran for 698 yards and 5 touchdowns) was named to his first Pro Bowl team.

He also reached a decision: he would play one more NFL season, then walk away.

He wasn’t loud about it. There was no press conference. Few — if any — of the Raiders were aware. But with age and experience, he was beginning to appreciate the finite nature of time, as well as all the experiences he was missing with his expanding family.

Linda, now his wife of four years, was largely raising their three children solo, while simultaneously pursuing her PhD in clinical psychology at Auburn. Bo was sensitive to her needs and aware of the athlete wife’s sacrifices.

“When I leave the ballpark, I become a father and a husband,” Jackson once explained. “And I don’t resume that other role until the next morning.”

Having been raised without a father, Jackson wore the pain of an ignored child. He didn’t wish to inflict that on his own offspring.

Plus, as much as he liked football, he never cherished the game. It was barbaric and brutal and left its participants in all sorts of disrepair. He’d seen retired Raiders invited back to a practice, limping on shredded knees and hollowed spines, sometimes flailing to grasp a memory that had escaped them.

What was my quarterback’s name? Who was that game against? Where are my car keys?

The sport was unforgiving; the practices long and boring and graceless. Did he aspire for his sons to one day suit up and carry the pigskin?

“No way,” he said. “Never.”

Plus, while he felt a kinship with a handful of Royals (through the years a number of baseball teammates wound up on the sideline of Raider games), the same did not apply to his NFL brethren. With the sometimes exception of Howie Long and Bill Pickel, a pair of Los Angeles defensive linemen, the Raiders were mere co-workers.

Jackson much preferred the rhythms of a baseball season — beginning with the optimism of spring training and lazily winding its way through the months.

Super Bowl hopes

With a 12-4 record and the AFC West title, the Raiders entered the playoffs as a serious threat to reach the team’s first Super Bowl in seven years.

Jackson would enjoy it and hopefully raise the Vince Lombardi Trophy — then play one more season before devoting himself full time to baseball and fulfilling his destiny of becoming the next Joe DiMaggio/Mickey Mantle/Roberto Clemente (none of whom he would recognize).

As a divisional title holder and owner of the AFC’s second-best record, on January 13, 1991, Los Angeles hosted 9-7 Cincinnati, the Central Division champion that destroyed the Houston Oilers one week earlier, 41-14.

On the night before kickoff, several Bengals came down with food poisoning. By two in the morning Boomer Esiason — one of the league’s elite passers — was hallucinating. By three, he and a dozen teammates were attached to IVs and expunging tragic volumes of waste from multiple orifices.

“I was up all night and uncertain whether I’d be able to play,” Esiason said. “I don’t think I’ve ever been that sick. I’ve always wondered whether Al Davis somehow food-poisoned us. It wouldn’t be beyond him.”

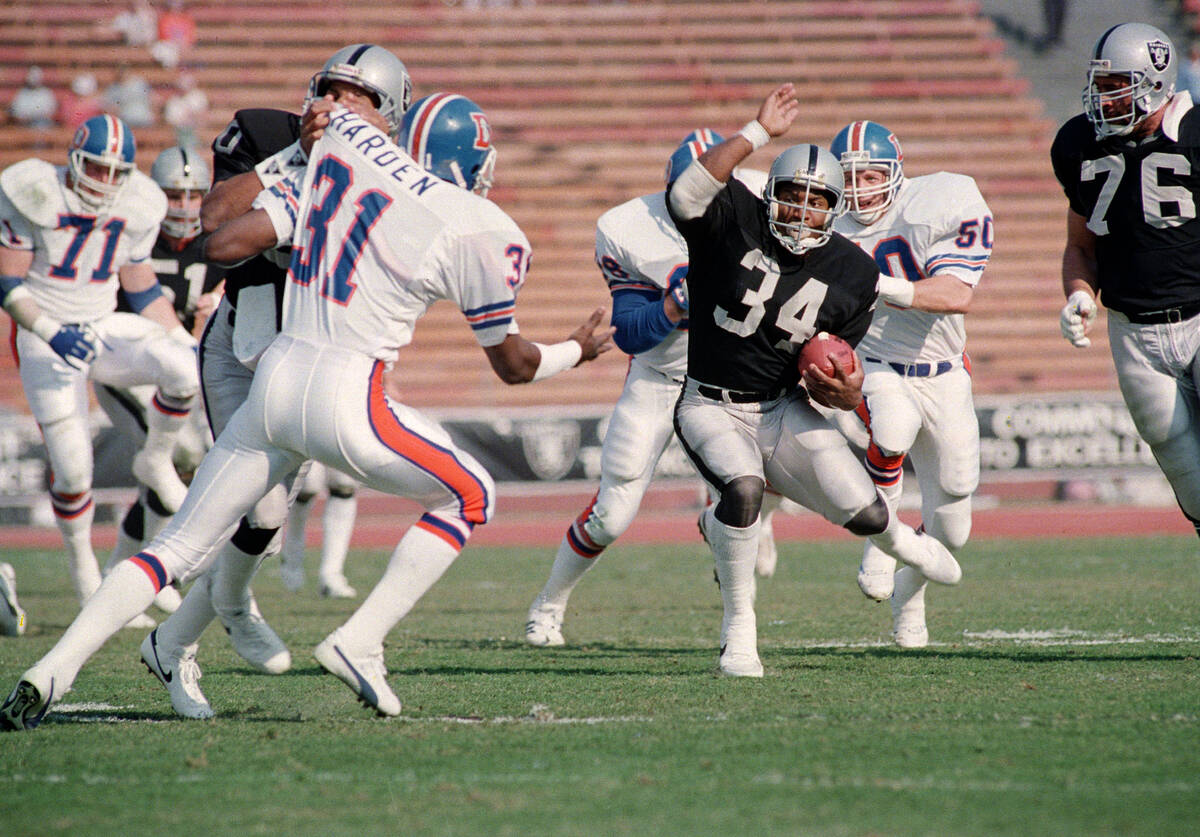

When he wasn’t fretting over his legion of upchuckers, Sam Wyche, Cincinnati’s head coach, was hyperfocused on stopping Bo Jackson. The Los Angeles Times referred to Jackson as a “Bengal Tamer.” He’d faced Cincinnati two times, running for 276 yards (an average of 13.1 yards per carry). In the last two games against the Bengals, Jackson pulled off runs of 92 and 88 yards.

In the lead-up, Wyche was honest in his hopelessness.

“He’s so fast,” he said, “that he is going to be gone before you can react.”

Hollywood buzz

Nike wanted to make certain its star client’s first-ever playoff experience was viewed by the largest audience possible. Hence, a day before kickoff, the company purchased 9,000 tickets to the Los Angeles Coliseum, thereby ensuring a blackout would be lifted and the game could be televised in Southern California.

The temperature was 60 degrees. It was windy, and the sky was cloudless. Oddsmakers had the home team as a seven-point favorite. Dick Enberg and Bill Walsh, the former 49ers coach, found themselves in the NBC broadcast booth.

Since arriving in Los Angeles eight years earlier, the Raiders had sought out Lakers-like Hollywood buzz with little success. The team never had its own Magic Johnson, flashing a million-watt smile. It never had the intimacy of the Forum, the sex appeal of the Laker Girls.

On this afternoon, however, something clicked. The sidelines were overflowing with celebrities — boxer Evander Holyfield, rapper MC Hammer, actor James Garner. Jackson invited several Royals teammates, including pitcher Mark Gubicza and George Brett, the future Hall of Famer.

The Coliseum was a centerpiece of sports and entertainment, and the main draw was Bo Jackson, backup.

Because Art Shell long ago abandoned the two-Heisman backfield, Los Angeles began with Marcus Allen at halfback, Steve Smith at fullback. The team’s opening drive was fruitless, and after the Bengals were forced to punt on the next possession, the Raiders returned to the field with Jackson at halfback.

His first carry came on second and 10 from the Los Angeles 39, and after slicing through the right side of the line and stomping over linebacker James Francis, he stumbled forward … and fumbled.

The ball rolled from his arms and into the awaiting grasp of safety Barney Bussey. Cincinnati’s defenders celebrated as if they’d won the lottery, and Walsh said, “This is what the Bengals had hoped for, and anyone who favors the Bengals knew they needed these types of things to happen.”

Only, the officials blew it, deciding that Jackson had fumbled after hitting the ground. Despite righteous protestations from Cincinnati’s staff, rules were rules. Jackson was credited with a 6-yard gain. He didn’t have another carry until early in the second quarter, when he burst through the middle of the field and was tackled after a 9-yard pickup.

On the very next play, he again punched up the Bengals’ gut for a second-straight 9-yarder. Then, for the third-straight time, Jackson grabbed the ball and chugged past the defensive line and into the secondary for 18 yards. After being brought down, Jackson pumped both fists in the air.

“What can you say?” bellowed Walsh.

By halftime, Jackson had 43 yards on five carries, and while Los Angeles only led 7–3, there was an ominous feeling inside the Bengals locker room.

“You knew what Bo was capable of doing, and you just sorta expected something amazing to happen whenever he touched the ball,” said Tim Krumrie, the Cincinnati nose tackle. “You hoped for the best, you gave it your all, but you were aware that, with Bo, it was a matter of time.

“Honestly, your only hope was him getting hurt. But he seemed indestructible.”

Bengals counterpart

On that Sunday in early January, there was one uber-famous participant in the Bengals-Raiders game who:

■ Was abandoned by his father.

■ Was raised alongside multiple siblings by a belt/extension cord-wielding single mother who did not want her children playing football.

■ Was highly recruited out of high school in both football and baseball.

■ Played both ways on the high school gridiron, but starred at running back.

■ Was brought up in an all-Black neighborhood but attended a majority-white high school.

■ Scratched and clawed for everything he achieved.

There was also the Bengals’ starting inside linebacker, who had a similar upbringing.

Kevin Walker’s father, Robert, left home when his second of four children was only five, leaving Qrinne Walker to raise her kids on a bookkeeper’s salary in a three-bedroom home on Yawl Avenue in West Milford, New Jersey.

Though he longed to play in his town’s youth football league, Kevin was forbidden by Qrinne. Instead of organized ball, he and his brother Robert would head down to the basement, slip tube socks over their sneakers and play one-on-one tackle football on the concrete floor.

“I had one of those kiddie football uniforms that came in a plastic tube,” Walker says. “It was a number 66 Packers jersey. Ray Nitschke. So I’d pretend to be Nitschke and we’d pound each other.”

By her son’s first year at West Milford High, Qrinne had a change of heart. Kevin was the freshman class president and an A student. A good kid.

“I’m sure it terrified her,” Walker said. “But she finally let me play.”

In his first-ever prep game, Kevin returned a kickoff for a touchdown.

Over four seasons he starred as the Highlanders’ starting halfback and strong safety, as well as the baseball team’s All-State power-hitting left fielder.

By his senior year, Walker was being recruited by many of America’s college baseball powerhouses. His true passion, however, was reserved for the gridiron.

“I loved everything about it,” said Walker. “Wearing your jersey, putting on your helmet. Hitting. Being hit. The crowd noises. The smells. The feeling.”

Walker signed at the University of Maryland as a running back. After a frustrating freshman year, his life was changed by Bobby Ross, the Terps’ head coach.

“Son,” Ross said, “you run a 4.5. There are a lot of running backs who can run a 4.5. But I don’t know of any linebackers who can run a 4.5.”

As a Maryland junior, Walker noticed NFL scouts starting to take an interest. As a senior, he was one of America’s best players and — with 172 tackles — leading ball hawks. When the Bengals grabbed him 57th overall in the 1988 Draft, Qrinne was overcome by emotion.

“You have this dream,” he said, “but you never know whether it’ll really happen. Suddenly I’m playing against Dan Marino and Eric Dickerson and Joe Montana, thinking, ‘Holy, cow! I’ve made it! I’ve really made it!’”

Walker did little his first two NFL seasons, but by 1990 he was starting at inside linebacker. Though never confused for Lawrence Taylor or Mike Singletary, he was a smart player who always seemed to wind up in the right spot at the right time.

“Kevin was very solid,” said Carl Zander, a Bengals linebacker. “He was definitely a head-in-the-game guy.”

Through the first half of the Raiders matchup, much of Kevin Walker’s life was devoted to keeping tabs on Jackson. Those first two 9-yard runs? The man who brought him down was Walker. That 17-yard gain? The man who missed — Walker.

“We were sort of playing a variation of the Bears’ 46 Defense that day, and I’d line up outside the tight end to give Bo and Marcus only one side to run,” Walker said. “That doesn’t mean they’d avoid my direction, but it would give them pause to head that way. If Bo got the ball and came toward me, I’d try and go right at him. If he went the other way, I was in pursuit.”

The Raiders received the second-half kickoff, and started off on their own 23. On first down, with Allen behind him as the lone setback, quarterback Jay Schroeder took a three-step drop and wildly misfired to a wide-open Mervyn Fernandez.

When the play ended, Jackson trotted back onto the field. The next call from Terry Robiskie, the offensive coordinator, was 28 Bo Reverse Left, which involved Allen lining up to Jackson’s right, three steps forward. This was not the way to Marcus Allen’s heart. If he said it once, he said it a hundred times: I am not a blocking back.

He was — for now — a blocking back.

The Raiders had wide receiver Tim Brown split far left, Fernandez far right. Tight end Ethan Horton was packed in alongside Rory Graves, the left tackle.

Anticipating a run, the Bengals featured four down linemen, two safeties close to the line and linebacker Leon White directly in front of Horton and Walker — wearing number 59 with trademark blocky shoulder pads — prowling forward as Schroeder barked out the signals. By the time the ball was snapped, Walker was prepared to charge and — hopefully — cut off any advancements.

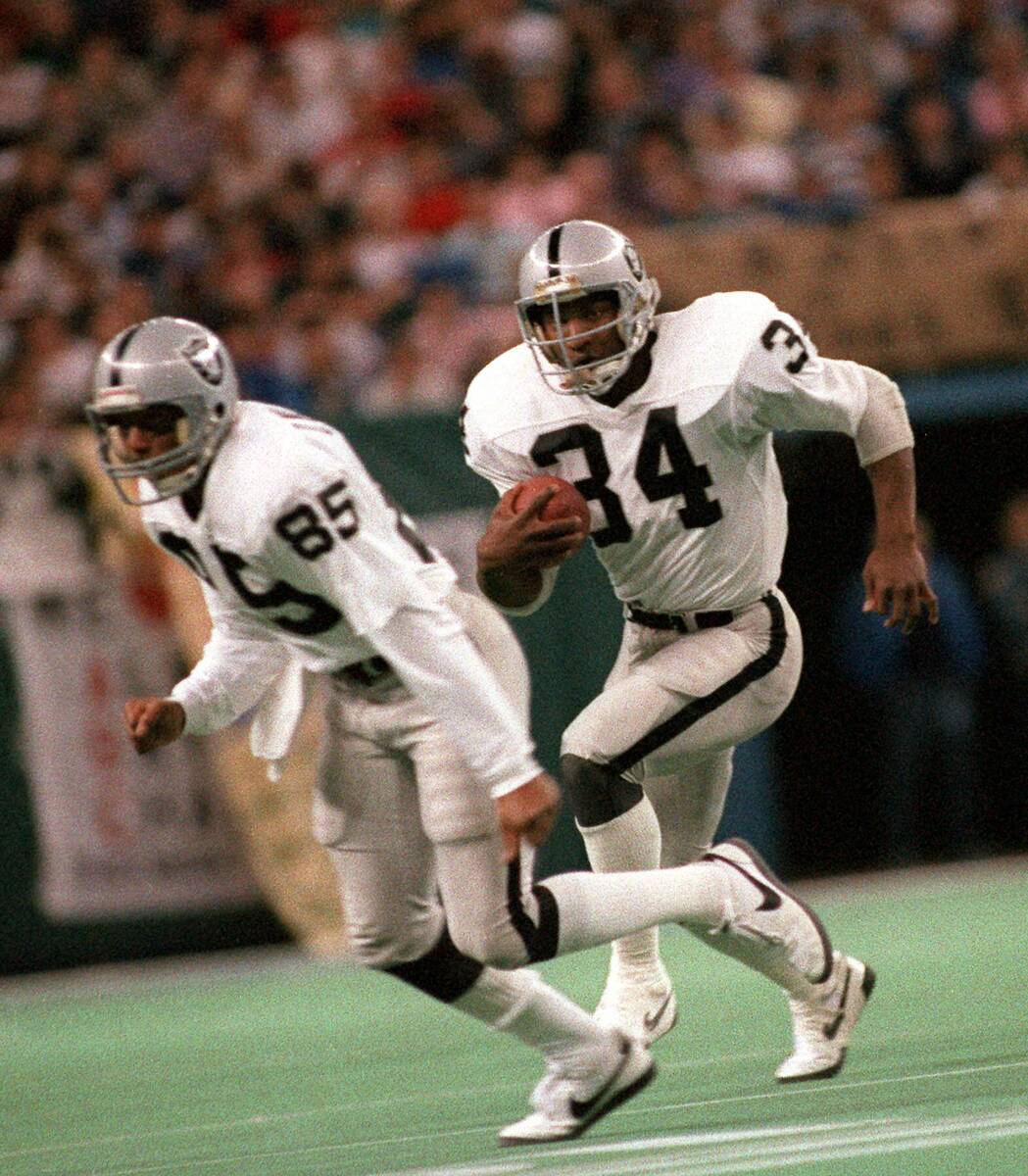

Within a second of taking hold of the football, Schroeder flipped it to Jackson, who followed Allen to the right. Walker was three steps into the backfield by the time the exchange took place, and as Jackson began his burst the linebacker tried cutting across the field in what would surely be a futile pursuit. Jackson, after all, ran a 4.17 40. Walker did not.

Allen’s block on White opened a gaping hole, and Jackson squared his shoulders, raised his knees and was off to the races.

“I was right there on the sideline,” said Vince Evans, the Raiders’ backup quarterback. “It looked like Bo was about to take it to the house.”

‘Got on my horse’

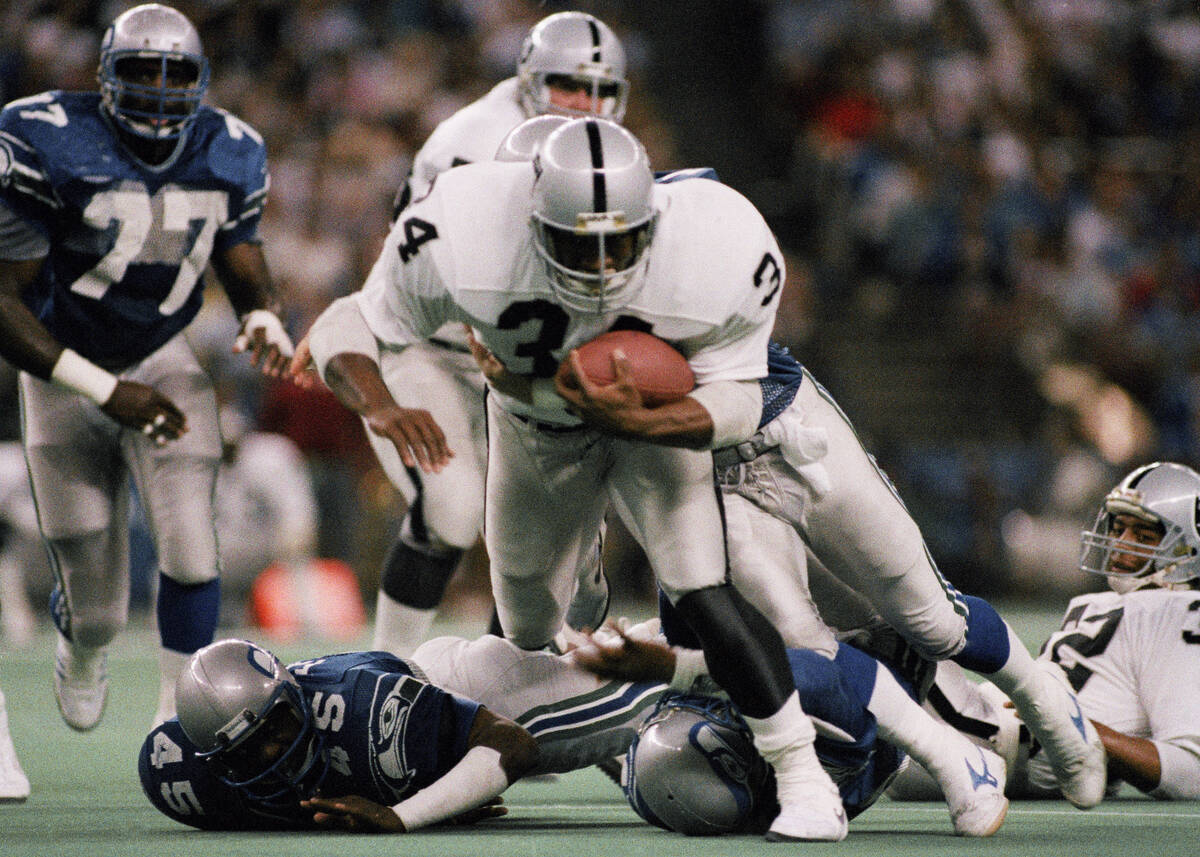

For 10 yards he sprinted untouched down the right sideline, and only slowed when David Fulcher, the free safety, arrived from the far side of the field. With a quick stutter step, however, Jackson left Fulcher lunging in his vaper trail, and continued on his path toward the end zone.

Unfortunately for the Raiders, that one-tenth-of-a-second sliver in time — Fulcher stepping in, Jackson stopping-then-going — served as a delay.

In that span Walker somehow returned from the depths and charged from Jackson’s left. Jackson tried to keep him at bay with a left-handed stiff arm, but Walker ran through it and reached out both arms to wrap the torso.

“I got on my horse from an angle and said, ‘I’m gonna try and cut him off,’” Walker said. “Maybe I can get him on the ground.”

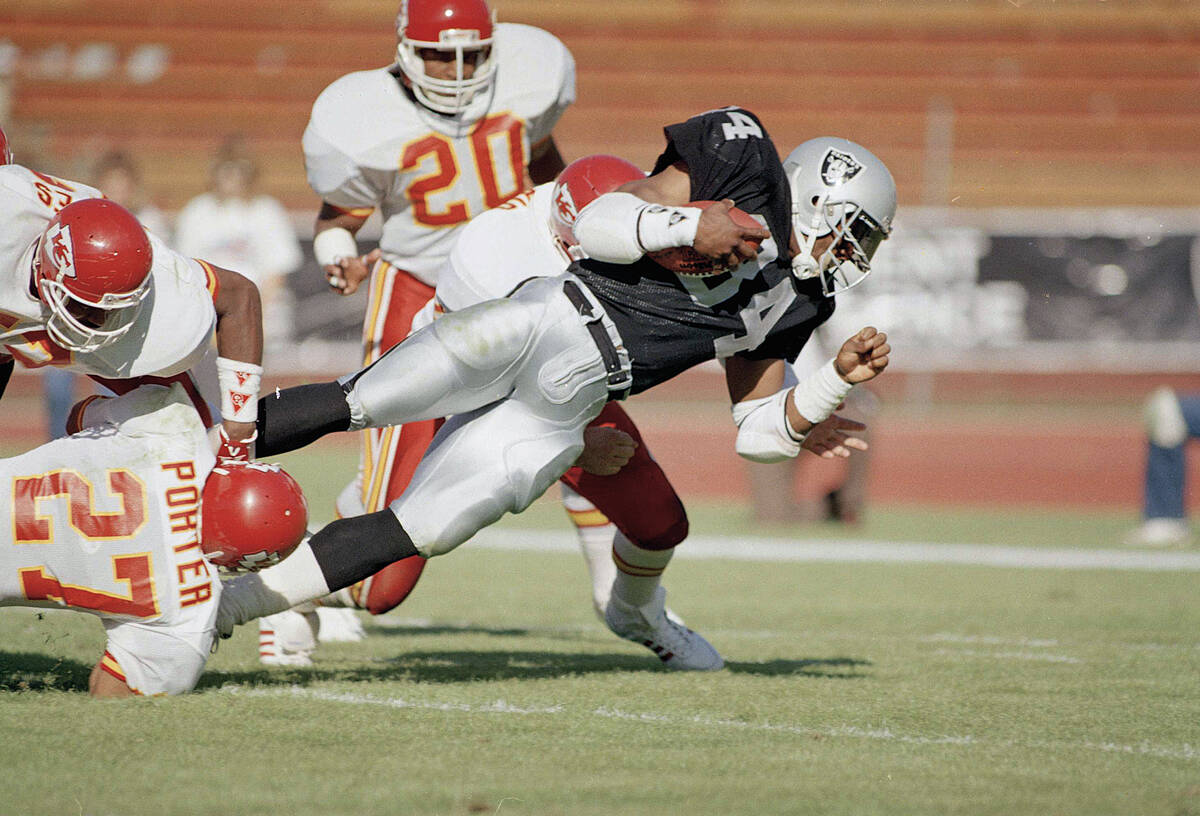

It was, of course, not that easy. The running back kept heading forward, and the linebacker slid down Jackson’s legs. He hung on to a right calf for dear life.

“It was almost like Bo threw his torso forward,” said Evans, “but the pull of the other guy pulled him back.”

That’s what finally brought Bo Jackson down — Herculean strength be damned, no man can run with a 238-pound anchor affixed to his calf. So as Jackson’s body propelled forward, his right leg remained within Walker’s grasp and his left leg (and, by extension, hip) was firmly planted in the turf.

“The momentum of my body kept going,” Jackson said, “and my left leg was extended to the point where I couldn’t bend it and fall.”

By the time the play ended, Jackson had scampered 34 yards down the field. The Coliseum crowd went berserk — the Los Angeles Raiders were on the attack.

“This is just what the Bengals wanted to avoid!” said Walsh. “And just what the Raiders were expecting sooner or later to happen!”

There.

Was.

Just.

One.

Teeny.

Tiny.

Problem.

Bo Jackson wasn’t getting up.

“I was one of the first over to him after the play,” said Horton. “I was whooping and hollering — ‘Yeah, Bo! Great run!’”

Jackson, he noticed, didn’t move.

“Come on, Bo!” Horton yelled. “Let’s go!”

“I can’t,” Jackson replied stoically. “My hip — something’s wrong.”

Like ‘ice pick’

As the fans cheered and the Bengals licked their wounds and the announcers offered praise, Jackson was rolling himself over, wondering what, precisely, had happened. He was quite certain his left hip popped out of the socket, so he wiggled his body and — he later insisted — popped it back in. He rose gingerly, but the pain was unfamiliar and intense.

It felt like somebody “had jabbed an ice pick up in there,” Jackson said. He returned to his back, and the team’s medical staffers, along with Shell, rushed to the field and surrounded him.

Once again, after several seconds, he lifted himself up, now sans helmet. Another round of cheers. It all appeared relatively normal.

“He may have pulled a muscle as he was trying to pull away from a tackle,” Walsh said. “Because he really wasn’t hit on the knee.”

Following a few clumsy steps, Jackson placed his right arm over the shoulder of H. Rod Martin, the team trainer, and his left arm over Napoleon McCallum, the running back. He was helped off the field. Once again Walsh, with a medical degree from the University of Random Guessing, diagnosed a pulled muscle.

But under closer inspection, there was reason for alarm. Bo Jackson’s face was contorted. He appeared as if he were hurting. He also looked to be somewhat scared. None of this was normal.

‘Tears in his eyes’

“There were tears in his eyes,” said Jamie Holland, a Raider receiver. “That, I remember.”

The general belief was that Bo Jackson’s return was inevitable. He was constructed of cement and Tungsten, and after a few moments he would certainly grab his helmet and get back to the action.

Only, that didn’t happen. As Los Angeles began to pull away for a 20–10 win, Jackson entered the locker room, where the training staff cocooned his left leg from groin to thigh.

“Bo knew something was really wrong,” said Dan Land, a Raiders defensive back. “He wasn’t naive about it.”

Jackson returned to the sideline, where he sat until the final gun. At one point he was approached by George Brett, gifted with a sideline pass.

“Bo,” Brett said, “you’re OK, right?”

Jackson frowned. “Nah, George, I’m not,” he replied. “I think my hip went out of the socket, then went back in.”

Late in the fourth quarter, Jackson asked Mark Gubicza, also on the sideline, whether he could fetch his sons, Garrett and Nicholas, from the stands, where they were sitting with Linda. “Of course,” said the Kansas City pitcher.

By the time Gubicza brought them to their father, the game was nearly over, and Jackson appeared to be in shock. His face was expressionless. He said very few words. The whole Bo Knows ad campaign was fun exaggeration (he couldn’t literally do everything), but Jackson considered himself to be indestructible. He could fight through any tackle, leap any obstacle.

Pain was something others felt. Not Bo Jackson. Now, though, he was experiencing excruciating pain.

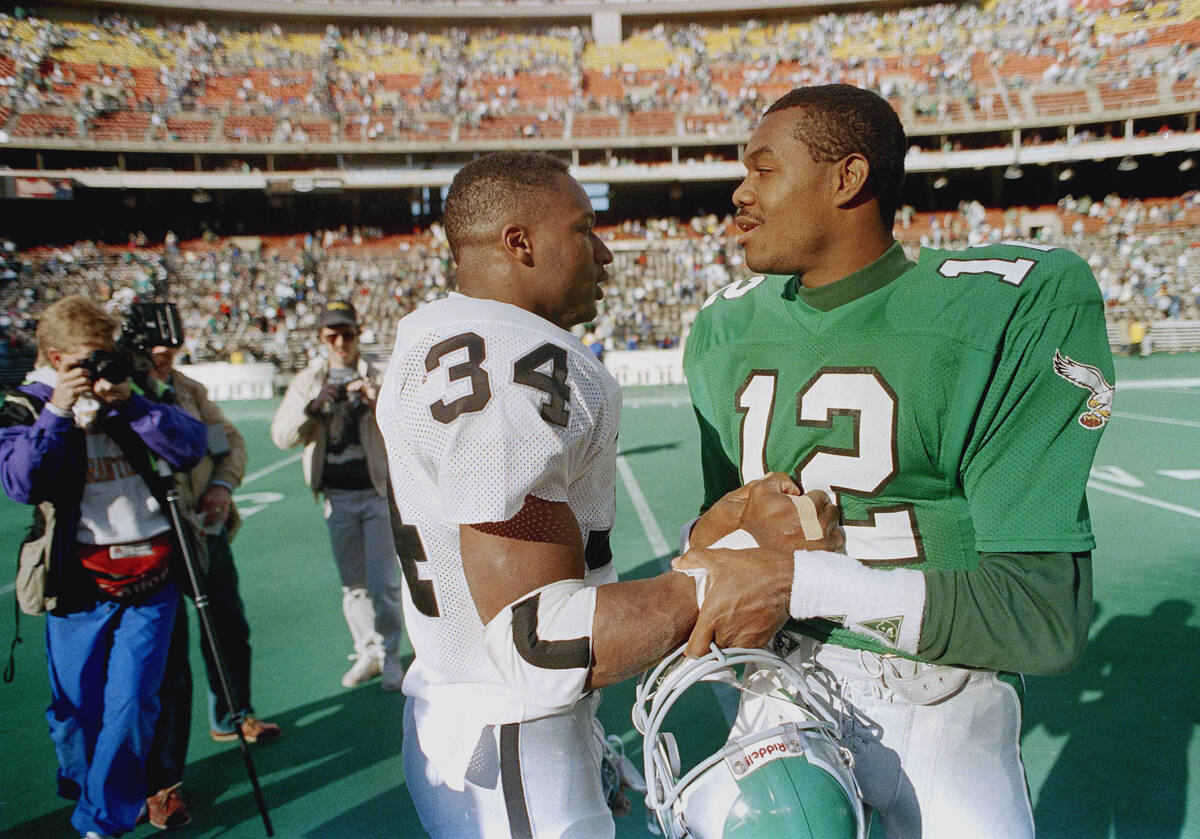

As soon as the final second ticked off the clock, Jackson — sons by his side — limped into the Coliseum’s home locker room. Although Walker did nothing wrong, he sought Jackson out.

“Bo … Bo — I’m Kevin,” he said. “I tackled you.”

“I know,” Jackson said.

“I’m so sorry,” Walker said. “How are you feeling?”

“I’m sore,” Jackson replied. “But it’s no big deal. I’ll be back next week.”

Walker loved to hear that.

“Well,” he said, “I’ll certainly be rooting for you.”

The men shook hands, and Jackson shuffled off.

“I’ve never spoken to him again,” Walker said thirty-one years later. “That was the last time I saw him.”

The Raiders were always known as a loose outfit, and the postgame locker room scene did nothing to dispute that. As soon as the injury occurred, Jackson should have been wheeled off and rushed to a hospital for testing. Instead, there he was, changing at his stall, showering, taking a handful of questions from the media before heading off on a cart.

“It’s a hip pointer,” he told reporters. “I’m going to play next week.”

It was not a hip pointer. No one (besides Jackson) said it was a hip pointer. There was no actual reason to believe it was a hip pointer.

A hip pointer is a deep bruise to the ridge of bone on the upper outside of your hip. Hip pointers hurt. They don’t hurt like this.

“I had (hip pointers),” said O.J. Simpson, working the game for NBC. “They only come from a real jolt, such as a helmet hitting the spot. I saw him go down. It was something else.”

Sitting in the Coliseum stands was Dr. Marcella Flores, a Portland, Oregon–based emergency room physician and the sister-in-law of Amy Trask, an employee in the Raiders’ legal affairs department. When the game concluded, Flores sought out Trask.

Avascular necrosis

“Amy,” she said, “you better be concerned about Bo’s injury.”

“I don’t think we’re too worried,” Trask said. “It’s probably a bruise.”

“I’m telling you, that didn’t look like a bruise,” Flores replied. “If I were you, I’d be very concerned about avascular necrosis.”

Trask had never heard of such a thing. Avascular necrosis? Was that even a real injury? But she wrote it down and later approached Al Davis.

“I think we might need to be aware of this,” Trask said.

The Raiders owner listened. Or at least seemed to listen. Had he opened the nearest medical journal, he likely would have looked up “Avascular necrosis” and passed out.

This wasn’t, as Walsh twice suggested, a pulled muscle. It also wasn’t, as Jackson thought, a hip pointer.

Avascular necrosis, according to Cedars-Sinai, is a disease that “results from the short-term or lifelong loss of blood supply to the bone. When blood supply is cut off, the bone tissue dies and the bone collapses. If avascular necrosis happens near a joint, the joint surface may collapse.”

Tony Decker, a longtime Division I athletic trainer, explained it simpler: “The blood supply to the head of the femur is disrupted. Blood is how our bones are nourished, so it leads to arthritic changes of the bone and everything becomes affected.”

Back in 1990, not a whole lot was known about the condition. Some believed it could be treated with a cast. Others thought rest.

A few hours after the game, Jackson went out to dinner with Linda and the children. When he rose from the table, a current shot through his hip. The next morning the Raiders had Jackson undergo an MRI (magnetic resonance imaging).

He assumed the prognosis would involve rest and some sort of ice-heat healing thingamajig. Then a doctor pointed toward the image of Jackson’s left hip.

“Do you see all that dark stuff?” the physician asked.

“Yes,” replied Jackson.

“That’s blood,” the physician said, “in your hip socket.”

For the first time in his twenty-eight years on earth, Jackson — who was standing as he received the news — felt light-headed and nauseous. He sat down.

“Wow,” he said. “I really injured myself.”

No one — including Jackson — was 100 percent sure what it all meant.

He was indestructible. Zeus and Paul Bunyan and Hercules and Superman.

He didn’t get injured, because Gods don’t get injured. So this had to be a farce, right?

Right?

The Raiders issued a post-MRI statement: “Bo Jackson has an injury to his left hip for which he is now receiving treatment. There will be no status report until late in the week.”

Robert Rosenfeld, the team physician, maintained his belief it was not serious.

“It’s going to get well,” he said before adding, “I really don’t know what the injury is yet. That’s the trouble.”

Calls to Richard Woods, Jackson’s agent, went unreturned. The people at Nike were terrified. So were the Royals, who had long dreaded the inevitability of this moment.

Critics come out

Jackson suited up for one practice, but didn’t touch the field. He was ruled out for the following Sunday’s AFC title game at Buffalo, and the critics pounced.

The Santa Rose Press Democrat ran a boxed listing of all the times Jackson had to sit with an injury (the implication: he’s soft). Todd Christensen, the former Raiders tight end, was particularly nasty.

“Bo Jackson’s a baseball player,” he said. “I can’t think of a time when he played through an injury.”

Though Jackson certainly did not have to accompany the Raiders to Buffalo, he did so — even jogging gingerly across the field during pre-game. With the Bills up 41–3 at halftime, and the temperature a balmy 32 degrees, Jackson chose to spend the last two quarters of the 51–3 demolition inside the locker room.

Again — understandable considering his innards were bleeding. The following day, Bob Keisser of the Long Beach Press-Telegram unloaded.

“Bo Jackson showed his true colors Sunday in Buffalo,” he wrote, “and they weren’t silver and black.”

Jackson read none of it. He flew back to California with the rest of the Raiders, bid a fond farewell at the airport and told a couple of his closer pals on the team he would see them “real soon.”

His football career was over.

Excerpted from the book “The Last Folk Hero” by Jeff Pearlman. Copyright © 2022 by Jeff Pearlman. From Mariner Books, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. Reprinted by permission.