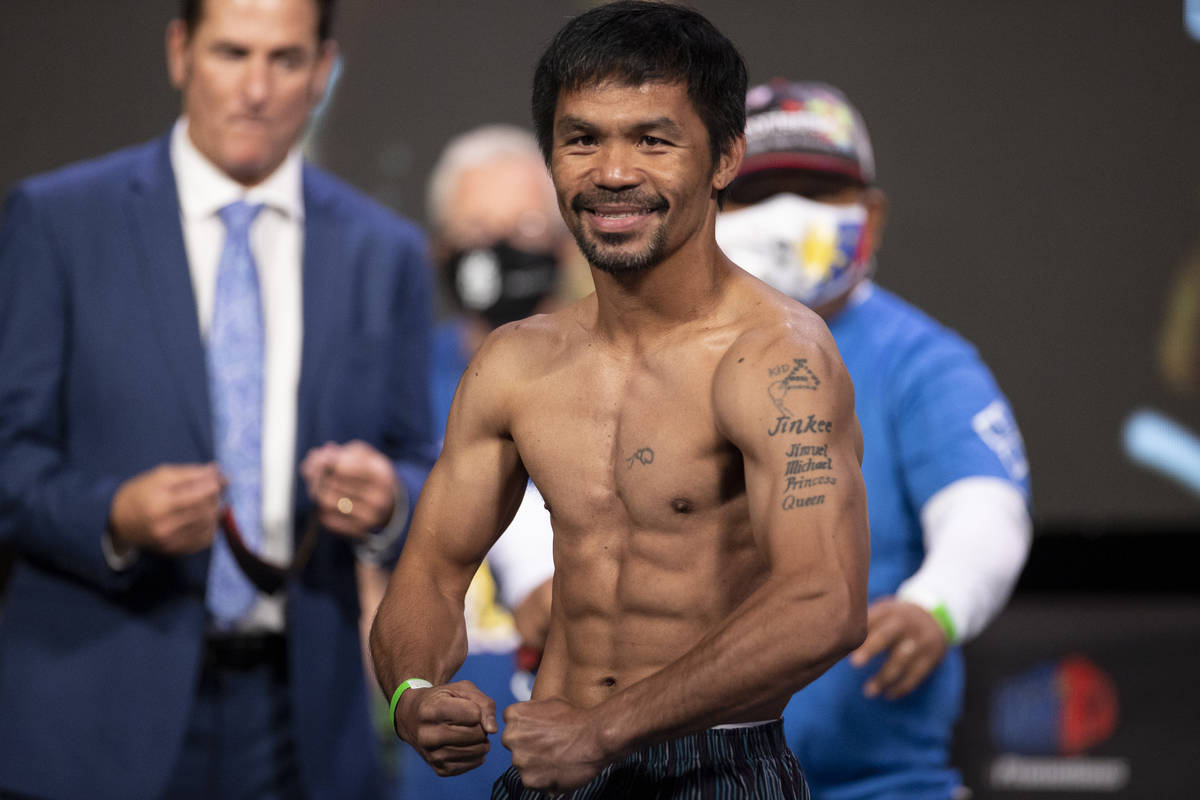

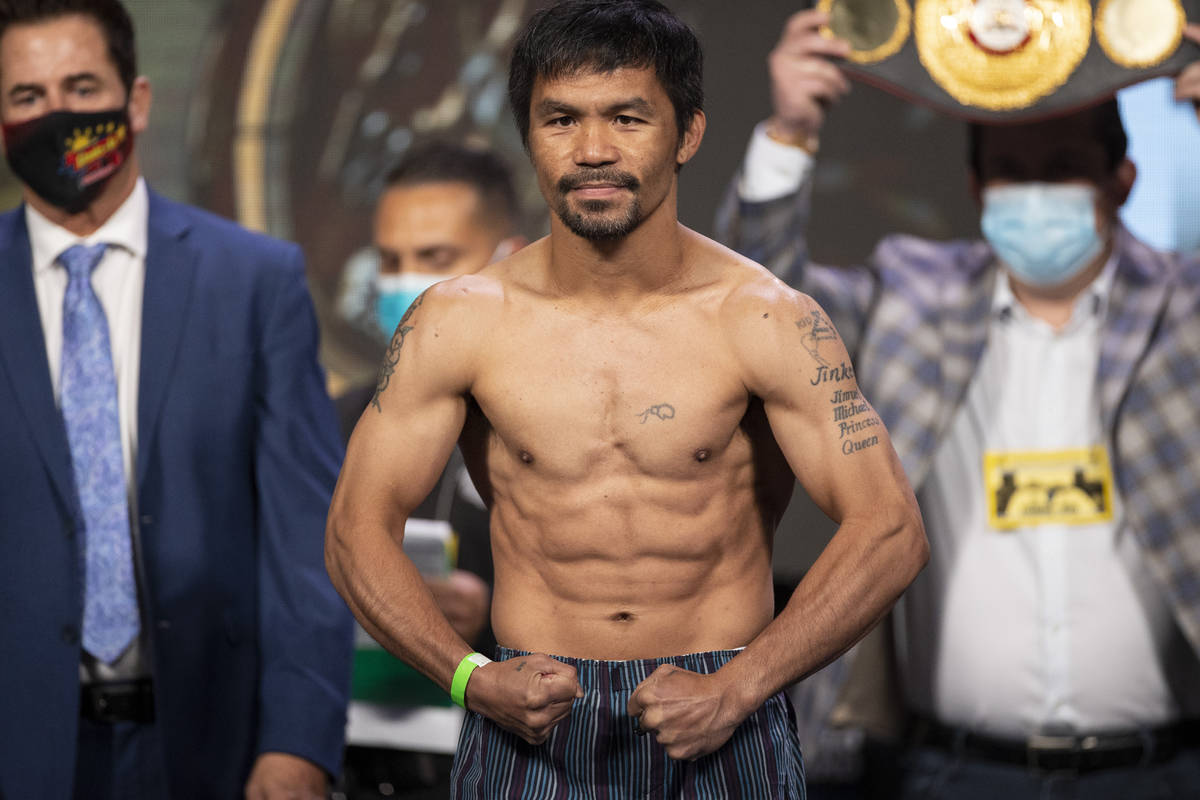

Manny Pacquiao amazingly holds his own against Father Time

WEST HOLLYWOOD, Calif. — He may be 42. Grizzled by 26 years of professional boxing and another 11 as a politician in his beloved Philippines.

But when fighting Filipino Sen. Manny Pacquiao steps in the ring inside West Hollywood’s famed Wild Card Boxing Club opposite longtime trainer Freddie Roach, the boyish grin quickly returns to his face. A youthful, tireless bounce replaces a measured, refined gait.

And age is rendered irrelevant.

“The thing is, he still loves boxing and knows that’s what he does best,” said Roach, Pacquiao’s trainer for the last 20 years and counting. “I’d like to see him retire someday and maybe be the president of his country, but we’ll see.”

Pacquiao (62-7-2, 39 knockouts) will fight at least once more on Saturday. This time at T-Mobile Arena against WBA welterweight champion Yordenis Ugás (26-4, 12 KOs), who replaced his original opponent, unified champion Errol Spence Jr.

But all bets are off beyond that. Pacquiao has hinted that this may be his last fight — meaning one of the greatest careers in boxing history would finally come to an end.

The stakes have made this week surreal for seemingly everybody involved, except Pacquiao, the eight-division champion who made his American debut 20 years ago in Las Vegas.

For he wants only to cherish this particular moment. To focus on this particular fight against this particular opponent.

“I never thought that I could be boxing this long in my career,” he said. “It’s a blessing.”

One of one

Pacquiao’s fight against Ugás will be his 20th on a lucrative pay-per-view platform that helped him earn more than $440 million in the ring. But he hasn’t forgotten his first purse: one dollar, that he used to buy rice.

The perils of poverty in the Philippines drove Pacquiao toward boxing, a fickle sport that often devours the fighters that drive it. But boxing wouldn’t use Pacquiao. He would use boxing to transform from a wandering street urchin into one of the most revered athletes on the planet.

Street fights became sanctioned fights on Jan. 22, 1995, when at 16 he made his professional debut as a 98-pound junior flyweight. He fought 10 times that year, realizing rather quickly that he could profit from his fast hands and fleet feet. His local legend began to blossom, and on Dec. 4, 1998, he won the first of his 12 titles — beating Chatchai Sasakul to capture the WBC flyweight strap in Thailand.

Pacquiao lost the belt a year later, prompting a 10-pound jump to super bantamweight. He toiled away at 122 pounds before venturing in 2001 to California, where he would cross paths with Roach and change the course of boxing history.

Roach opened Wild Card in 1995, because “you never know when the next Muhammad Ali might walk through the door.” For Roach, that was Pacquiao, who walked through the door in the spring of 2001 after taking a Greyhound bus from San Francisco to Los Angeles.

“He spoke a little bit of English and he told me ‘I heard you’re good on the mitts, can you catch me?’” Roach recalled. “After one round, I said ‘This kid can fight.’ And he said ‘We have a new trainer.’”

Within weeks, the duo was fighting for the IBF super bantamweight championship against Lehlohonolo Ledwaba, regarded then as one of boxing’s best pound-for-pound fighters. Pacquiao was called two weeks before the June 23, 2001, fight date to fill in for an injured Enrique Sánchez at MGM Grand Garden.

He stopped Ledwaba in the eighth round, claiming a second world title and beginning his unprecedented trek toward the top of the sport. Over the ensuing decade, Pacquiao went on to win world titles in an additional six weight classes to become the only eight-division champion in boxing history.

“It was one fight after the other, and he just kept winning,” Roach said. “He was unstoppable.”

With Roach’s tutelage, Pacquiao evolved from a powerful southpaw into an ambidextrous punching machine. Equipped with the fastest hands in boxing, Pacquiao wouldn’t just beat his opponents. He would demoralize them.

“He just explodes with combinations,” said Timothy Bradley Jr., a former two-division world champion who fought Pacquiao three times. “The combinations don’t stop. They keep coming and coming and coming. … The pure tenacity that this guy fights with, the hunger, it’s just different.”

Pacquiao’s resume includes signature victories over Marco Antonio Barrera, Erik Morales, Juan Manuel Marquez, Oscar De La Hoya, Miguel Cotto and Antonio Margarito — all of whom are among the elite fighters of their era.

He retired De La Hoya in his welterweight debut, stopping him on his stool after eight brutal rounds. He reconfigured Margarito’s face despite conceding more than 15 pounds to the former 154-pound champion in his lone super welterweight bout.

Other notable wins include those over Bradley, Ricky Hatton and Keith Thurman, all world-class fighters when they fought Pacquiao.

All in all, Pacquiao has fought 24 current or former world champions.

“The kid was afraid of nothing,” said Top Rank chairman Bob Arum, who promoted Pacquiao throughout the course of his prime. “He had great confidence in himself and proved time and time again what a great competitor he was.”

Swan song?

Even now, Pacquiao wants to fight the best. Thurman was an unbeaten 30-year-old champion when he fought Pacquaio on July 20, 2019. Pacquiao dropped him in the first round en route to a decision victory.

He waited patiently before selecting his next challenge: Spence, a unified champion in his prime regarded as one of boxing’s five best pound-for-pound fighters. But Spence withdrew from the fight earlier this month with a torn retina, forcing Ugás to step in on two weeks’ notice.

The news was certainly disappointing for Pacquiao, who was eager for an opportunity to make yet another statement about his boxing brilliance. But it hasn’t affected his preparation or dampened his enthusiasm.

“I feel young right now. I’m just happy with what I’m doing, because boxing is my passion,” Pacquiao said. “I enjoy training camp. I’m excited to sacrifice and be disciplined every day to prepare for a fight like this.”

This may well be Pacquiao’s swan song. He’s suggested as much throughout the course of the promotion. But he’s yet to make a definitive declaration about his future. In boxing. Or in politics.

He may wait for Spence to recover or vie for a fight against WBO welterweight champion Terence Crawford. He could shift his focus toward a presidential run in the Philippines after five years in the senate with the election looming in May.

Perhaps he’ll do both. Don’t put anything past Pacquiao.

“I don’t think he wants to leave any stone unturned,” said Sean Gibbons, the president of Pacquiao’s promotional firm, MP Promotions.

Should Pacquiao beat Ugás, he’ll become the oldest fighter to win the welterweight championship, breaking the record he set two years ago by beating Thurman.

It would be yet another unprecedented achievement in an unprecedented career.

“There will never be another Manny Pacquiao in the sport of boxing,” Bradley said. “He’s legendary.”

Contact reporter Sam Gordon at sgordon@reviewjournal.com. Follow @BySamGordon on Twitter.