The plumes of snow-white smoke belching into the morning air mean it’s go time.

It’s a shade before 10 a.m. at Nellis Air Force Base on a recent Wednesday, and the camouflage ear plugs provided to visitors have come in handy.

It’s loud out here on the tarmac, where sound registers in the gut as much as the cochlea, something you feel and hear in jarring unison, like straddling a suddenly awakened fault-line.

The jets are lined up eight deep, F-16s with muzzles and tail fins painted a star-spangled red, white and blue.

The Thunderbirds are ready to roll.

One by one, they taxi down the runway after emitting a test blast from their smoke machines.

The first four roar into formation together, refracting the sun’s rays in a gleaming diamond pattern in the sky.

The next two fly solo; the final pair videos and narrates the action.

It’s a scene that’s repeated itself daily for decades now.

On June 1, the Thunderbirds will commemorate 65 years in Las Vegas.

During that time, they’ve performed thousands of air shows in front of millions of fans, demonstrating what jet fighters can do when pilot and plane are pushed to the limit at once.

The Thunderbirds’ story mirrors that of their home city’s: two former underdogs that have seeded themselves into the American consciousness with a mix of showmanship, ingenuity, razzle-dazzle and risk.

“I always compare it to when Tiger Woods started playing golf,” says Col. John Caldwell, commander of the Thunderbirds, explaining the rise of the squadron. “People started watching golf who never watched it before. The reason they did that was because he was excellent at the game.

“I think the American public craves seeing other humans do things in an excellent way,” he contends. “And that’s the draw of the team.”

‘Ambassadors of the Air Force’

It began when he was a kid, neck craned to the sky, eyeing his future in the clouds.

The son of a 20-year Air Force veteran, Kyle Oliver was to exposed to the Thunderbirds at a young age.

“I went to a lot of air shows and saw the team fly,” the Ohio native recalls from the VIP room next to the Thunderbirds Museum at Nellis, sitting near a metallic sculpture of an eagle the size of an engine block. “That’s really where I got my interest in aviation to begin with. I was super interested in flying fighters specifically because of my exposure to the team.”

He longed to become a member of the Thunderbirds one day.

As he grew older, though, Oliver began to wonder if his dream was merely a dream.

“I started having the big-kid conversations with myself,” he recalls. “ ‘Every little kid wants to be a fighter pilot, you’ve got to grow up. What do you really want to do? Get real.’ ”

And then he saw the Thunderbirds fly again at the 2005 Dayton Air Show.

“I remember it to this day, very vividly,” Oliver recollects, the memory warming his voice. “I said, ‘Nope, that’s it. I’m going to go make this dream happen.’ ”

He enlisted in the ROTC program at Ohio State University and joined the Air Force.

In 2019, he was chosen for the Thunderbirds.

His life had come full circle.

Tech. Sgt. Heidi Agustin is the material management specialist for the Thunderbirds at Nellis Air Force Base. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

Tech. Sgt. Heidi Agustin is the material management specialist for the Thunderbirds at Nellis Air Force Base. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye  Staff Sgt. Tory Osmundson is the client systems administrator for the Thunderbirds at Nellis Air Force Base. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

Staff Sgt. Tory Osmundson is the client systems administrator for the Thunderbirds at Nellis Air Force Base. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

Staff Sgt. Matthew Tolle films the Thunderbirds. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

Staff Sgt. Matthew Tolle films the Thunderbirds. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye  Maj. Kyle Oliver is the Thunderbirds 6-opposing solo pilot. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

Maj. Kyle Oliver is the Thunderbirds 6-opposing solo pilot. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye “I was through the roof. I was ecstatic,” Oliver says of his reaction upon learning the news. “I was so taken aback that I didn’t even bother to ask which position I’d been hired into.”

Oliver’s story is exactly what the Thunderbirds are intended to elicit.

“We’re the ambassadors of the Air Force,” says Tech. Sgt. Heidi Agustin, a material management specialist in charge of supply who’s been on the team for three years and originally hails from Los Angeles. “If you look at what our capabilities are, it’s a dream team, pretty much.”

Basically, they’re a high-flying, highly successful recruiting tool.

Their motto: Recruit, retain, inspire.

“Going out and meeting all of our fans, trying to influence the younger generation to join the Air Force or just inspire them to do things they want to do, I think that’s huge,” says Staff Sgt. Tory Osmundson, a fine systems technician originally from Washington.

The squadron dates back to 1953, when the Thunderbirds were activated as the 3600th Air Demonstration Unit at Arizona’s Luke Air Force Base. The Air Force had become its own separate branch of the U.S. military but six years earlier.

To simplify aircraft logistics and maintenance, the Thunderbirds moved to Nellis Air Force Base in 1956.

Their hangar is the oldest on the property.

That same year, the Thunderbirds switched to the F-100C Super Sabre, becoming the world’s first supersonic aerial demonstration team.

The squadron now consists of 12 officers — eight pilots and four support staffers — who serve a two-year tour of duty.

Each is officer is known by the number associated with his or her position.

For instance, Oliver, the opposing solo flyer, is referred to as “6.”

The Thunderbirds are rounded out by 130 enlisted personnel who generally serve three- to four-year terms.

Together, they’ve built the team into a worldwide attraction, performing as many as 65 shows a year.

This from a squad whose inauspicious start began with but seven officers and 22 enlisted members.

“You have to recognize that the Thunderbird brand was not an instant sensation,” Caldwell says. “We had to work really hard to build the prestige, the reputation and the credibility.

“The whole essence of the brand had to be built from nothing,” he continues. “It would take another 68 years in order to create something like we have today.”

The finest in flight

Eighteen inches.

That’s roughly height of four coffee cups stacked on top of each other.

That’s also how close the Thunderbirds fly next to one another during certain maneuvers.

There’s little room for error. There’s little room, period.

“It’s very challenging flying,” Oliver says. “For our solo opposing passes, my job is to make it look as if I’m going to hit Thunderbird 5 without actually hitting her. We’ll do opposing passes in front of the crowd where we’re passing with over 1,000-miles-an-hour of closing speed and inside of 100 feet, which is unheard of in fighter aviation. You’d get fired from any other job if you did something like that.”

And then there’s the whole trying-to-breathe-while-defying-gravity thing.

“I’m pushing the speed of sound and I’m pulling upwards of nine times the force of gravity throughout the show,” Oliver explains. “What that means is that when I pull back on the stick, I’ve got nine times my weight pulling down on me.

“It’s a struggle to stay seated upright,” he says. “It’s a struggle to keep breathing. It’s a struggle to make sure that you’re able to stay conscious and focus under those conditions.”

Staff Sgt. Matthew Tolle, who films the team, documents their exactitude firsthand.

“There’s so much behind all the maneuvers they do,” he says. “When they do their sneak pass, 6, he’ll come up right behind the crowd and he’s actually going .94 mach, which is about 750 miles an hour. That’s pretty fast. It’s kind of hard to control that, you know?”

A Thunderbird pilot helmet is displayed at the Thunderbirds Museum at Nellis Air Force Base. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

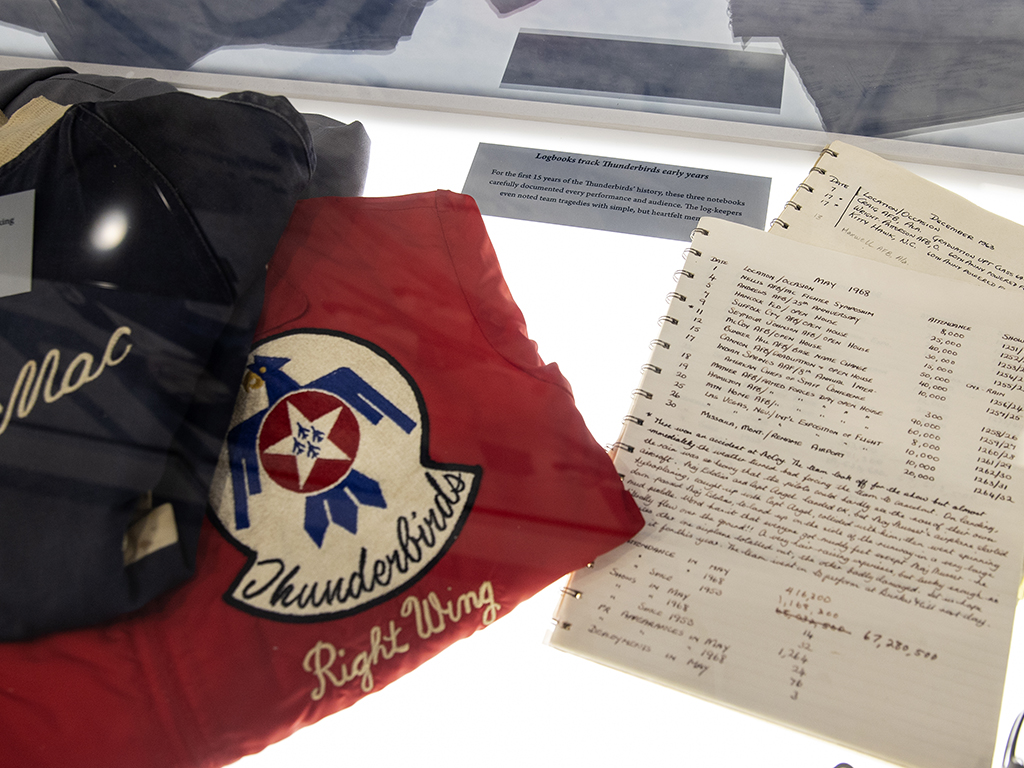

A Thunderbird pilot helmet is displayed at the Thunderbirds Museum at Nellis Air Force Base. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye  Thunderbirds pilot uniforms and flight logbooks are displayed at the Thunderbirds Museum at Nellis Air Force Base. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

Thunderbirds pilot uniforms and flight logbooks are displayed at the Thunderbirds Museum at Nellis Air Force Base. (Bizuayehu Tesfaye/Las Vegas Review-Journal) @bizutesfaye

To fly on the Thunderbird team, then, means being among the most skilled pilots in the Air Force.

An average of two to three new pilots joins the team each year, culled from a bevy of applicants.

Making the squad is hard, unlikely.

“It’s a long process,” Caldwell says. “It’s an emotional journey for a lot of people. From the time that you first see the team and the idea enters your mind that you want to be a Thunderbird to when you’re actually showing up and putting the uniform on, it can be years and years of applying.”

Caldwell takes a number of things into consideration when screening potential candidates for the team, ranging from personality — “We need somebody who has the charm, the charisma to engage with the American public and leave them with a sense of confidence in the military” — to technical expertise.

“They have to be in the top third of their career field,” he explains. “To execute the Thunderbird mission, because it is so difficult and demanding, we need the top performers in order to be here, so you’ve got to be a skilled technician at whatever it is you do, whether it’s flying, public affairs, doing on-aircraft maintenance. Doesn’t matter. You’ve got to be at the top of your game.”

Considering the dangers inherent in what they do, everyone pretty much has to be.

Twenty-one Thunderbirds pilots have been killed in the team’s history, though just three fatal crashes have occurred during air shows.

“When you’re flying formation the way that we fly, you have to want to fly well, you have to fight for every single inch,” Caldwell says. “We push ourselves past what’s comfortable.”

Road warriors

They tour more than most rock stars and their gigs are even louder.

With a season that runs from mid-March to late October/early November, the Thunderbirds perform an average of 60-65 air shows annually.

During that roughly eight-month span, they’re on the road four days a week, between 200 and 230 days a year.

The schedule for an average week: travel on Thursday, practice on Friday, game time Saturday and Sunday, head home Sunday night.

Repeat. Repeat. Repeat.

“Since I’m family-oriented, it’s kind of hard, with my wife, just kind of leaving her with the kids,” Tolle acknowledges. “For me, you almost feel guilty, because sometimes you’re on the road for 210 days a year.

“But you get acclimated after a little while,” he continues. “The first year’s rough. The second year it gets a lot better, and the third year you’re just like, ‘OK.’ ”

The crew travels together in a C-17 transport plane, carrying 17 tons of equipment to each show.

“The amount of time that we spend with each other is almost unbelievable,” Caldwell says. “We spend more time with each other on this team than we do our own families for the time that we’re a Thunderbird.”

Come showtime, emotions can run high.

Some people break into tears, Tolle notes.

“The first flyover we have, the diamond goes right over us and the faces people have, it’s crazy. They love it,” he says. “It’s more than just a pass-over, it’s the significance of the freedom that it represents. It’s crazy how much it touches people.”

Returning to Vegas, the Thunderbirds make a point of flying over the Strip.

Their lives are a series of destinations.

But only one home.

“We always work real hard to make sure that the city’s aware of the Thunderbirds, that they understand we’re part of this community,” Caldwell says. “There’s a lot of characteristics of the team that are reflected in the culture of the folks who live here.

“I think that the Thunderbirds are a part of the Vegas identity just as much as anything else that’s here,” he adds. “We want to be a part of the fabric of this community.”

Contact Jason Bracelin at jbracelin@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0476. Follow @JasonBracelin on Twitter and @jbracelin76 on Instagram