Fossil from Nevada cave spurs discovery of extinct horse

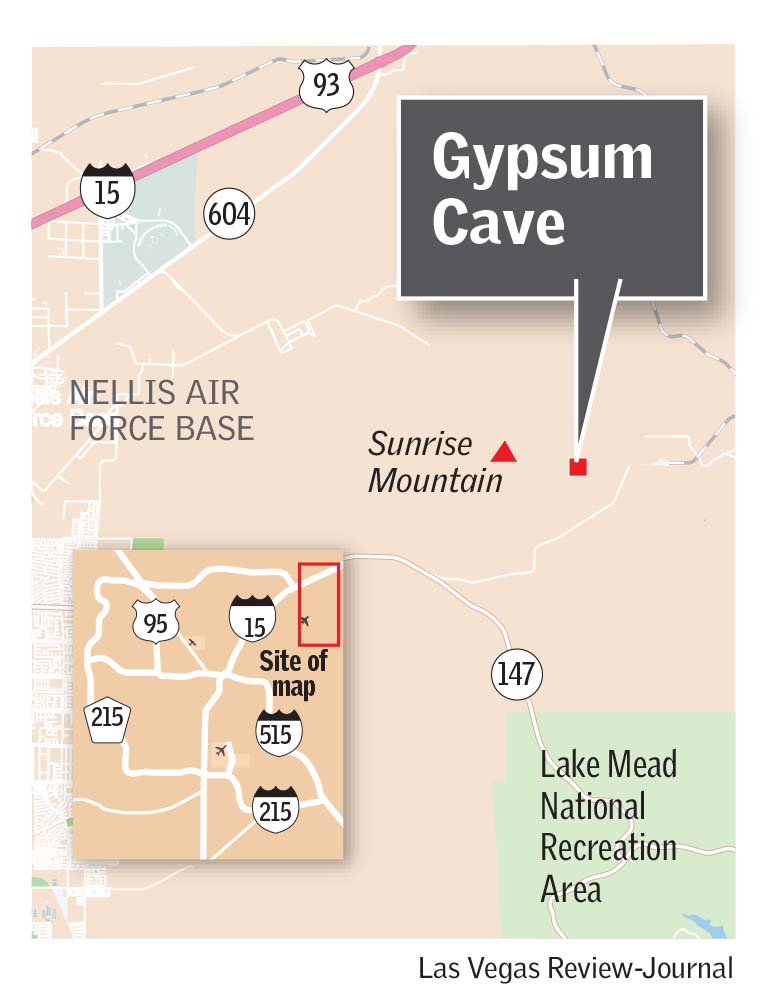

In the early days of the Great Depression, a team of researchers led by famed archaeologist Mark Harrington unearthed a treasure trove of animal fossils and ancient artifacts from a cave in the mountains east of Las Vegas.

Some of the bones found inside Gypsum Cave were so well preserved, they were mistaken for modern specimens and filed away in museum collections, where they went largely overlooked until recently.

Now a horse skull collected from the cave during Harrington’s expedition in 1930 and 1931 is helping scientists identify a new type of extinct, stilt-legged horse that died out during the last ice age.

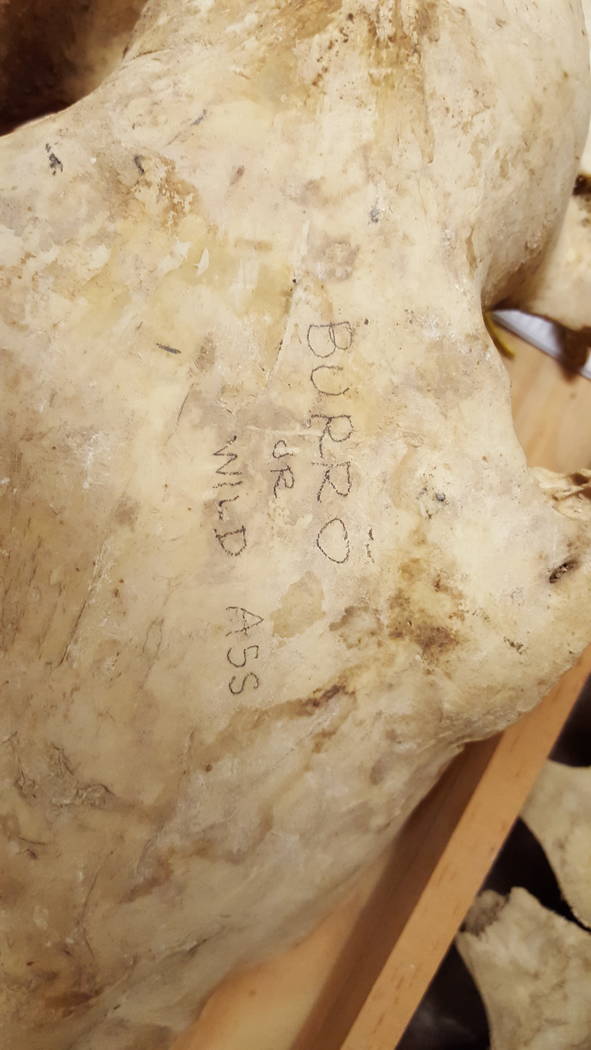

“The skull didn’t look particularly old or particularly ancient. It looked like last week’s lunch,” said paleontologist Eric Scott, who helped track down the mislabeled fossil on a shelf at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County. “Someone had even written in pencil across the top of the skull: ‘modern sample, wild horse or burro.’”

Instead, it turned out to be 13,000 years old and scientifically significant: the most complete skull ever found of a so-called “New World stilt-legged horse.”

“Here’s this priceless fossil that’s just sitting there being ignored,” said Scott, an ice age horse expert with California State University, San Bernardino, who has worked extensively in Southern Nevada.

A horse that isn’t modern

Scott was part of the international team of researchers that described the new genus of horse in a study published Nov. 28 in the journal eLife.

Their findings are based on analysis of ancient DNA extracted from the Gypsum Cave skull and other well-preserved bones from Natural Trap Cave in Wyoming and the Klondike gold fields of Canada’s Yukon Territory.

Before the new study, the lightly built horses with the long, thin leg bones were thought to be related to the modern Asiatic wild ass or simply a separate species within the genus that includes living horses, asses and zebras. The new results reveal that these extinct horses were not closely related to any living population. They were an evolutionary dead end that diverged from the main trunk of the family tree leading to Equus, the genus that includes modern horses, some 4 million to 6 million years ago.

“The evolutionary distance between the extinct stilt-legged horses and all living horses took us by surprise, but it presented us with an exciting opportunity to name a new genus of horse,” said the study’s senior author, Beth Shapiro, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

The team chose to call the new genus Haringtonhippus francisci after, not Mark Harrington, but Richard Harington, an accomplished paleontologist who spent his career studying the ice age fossils of northern Canada and first described the stilt-legged horses in the early 1970s.

Scott said the ability to extract and analyze DNA from well-preserved specimens like these is forcing researchers to re-evaluate what they thought they knew about some species that died off about 11,000 years ago.

“If the DNA is telling you one thing, and the bones are telling you something else, you go with the DNA,” he said.

Where history and prehistory meet

All told, the exploration of Gypsum Cave almost 90 years ago yielded evidence of the extinct Shasta ground sloth, large camel and llama, as well as the bighorn sheep, mule deer, grey fox and kit fox. There was so much stuff left behind by the sloths — a skull, backbone, claws and even some reddish-brown hair — that Harrington believed the animals must have used the cave as an ice age den. A thick layer of sloth dung on the cave floor provided scientists with a detailed menu of what ground sloths liked to eat and what was growing in the area at the time.

Harrington and company also cataloged tools and weapons made by early Indians and left in the cave over the past 2,000 years.

Gypsum Cave was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2010.

“It is cool that it’s both a paleontology site and an archaeology site,” Justin DeMaio, a Las Vegas-based Bureau of Land Management archaeologist, said during a recent visit to the cave.

The historic nature of the scientific expedition that unfolded there is icing on the cake, DeMaio said. “Mark Harrington was a huge name in paleontology throughout the West.”

While going through Harrington’s specimens from the cave several years ago, Scott and another researcher also identified bones from 10 individual horses, including some with ligaments, tendons, skin and hooves still present.

Some of the bones showed what appeared to be bite marks, possibly from a wolf, suggesting the animals were dragged into the cave by a predator, Scott said.

He called the rediscovery of the ice age horse skull “a nifty detective story” that demonstrates how persistence and a little luck can lead to scientific breakthroughs.

“There’s a lot of serendipity for all of this to come together at the time and in the way it did,” Scott said.

Contact Henry Brean at hbrean@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0350. Follow @RefriedBrean on Twitter.

Empty cavern

Some trash and graffiti are about all you’ll find inside Gypsum Cave these days, and the Bureau of Land Management would prefer it if people stayed out of the cavern altogether.

The site of archaeologist Mark Harrington’s early 1930s scientific expedition is now filled with potential hazards. It’s also an important spiritual site, known as Music Cave, to American Indians in the region, according to BLM archaeologist Justin DeMaio.

He said the federal agency has been working with tribal groups to clean up and preserve the limestone opening in the mountains east of Las Vegas.

BLM spokeswoman Kirsten Cannon said the dirt road leading to the cave was closed to vehicles in 1998, though visitors can hike into the site on foot.