Success stories show varied routes to victory

Hayden Fry believed so strongly that it takes a university village to run a successful college football program that he would not consider accepting a job offer unless he had complete support, including the school president’s.

He found such backing at seemingly hopeless places: Southern Methodist, North Texas State and Iowa. It was at that final stop where Fry would make his mark as the Hawkeyes became a power.

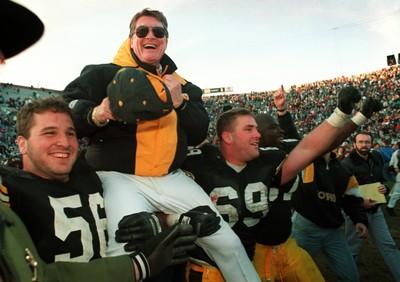

Until Fry made his way to Iowa City in 1979, the Hawkeyes were just about everyone else’s sure victory as they suffered 17 consecutive seasons without a winning record. But in 20 years under Fry, they amassed 13 winning seasons, 14 bowl appearances with six victories, and at least a share of three Big Ten Conference championships.

“The administration, with the president down to the faculty and athletic administration, must commit to an outstanding program,” Fry said. “Once the top people committed and realized the value, they were all for it.”

Fry was so certain it took more than innovative game-day strategy and exhaustive practices for players to turn a longtime loser into a winner that he overhauled just about every part of the program.

He created Tigerhawk, a marketing company that distributed Iowa memorabilia, and reached an agreement with all 62 J.C. Penney Co. stores in the state to carry the merchandise. Fry also asked permission of the Pittsburgh Steelers, who also wear black and gold, for Iowa to redesign its uniforms to closely match the best team of the 1970s.

“You have to change the image,” Fry said. “You change the color of the uniforms because you don’t want people looking at the same team that had been getting their butt kicked. You change the logo. You change the way you come on and off the field.”

Fry demonstrated that winners can be created just about anywhere.

Greg Schiano proved that at Rutgers. In 2005, he led the Scarlet Knights to their first winning season (7-5) since 1992 and first bowl appearance since 1978. Then last year, he became the first coach to direct the school to back-to-back bowl berths: a 37-10 victory over Kansas State in the Texas Bowl capping an 11-2 season.

Whether Schiano can sustain such success at a place that is still a newborn to the national spotlight is the question. The ultimate turnarounds have stood the test of time.

Though most fans remember only the long period of domination, Florida State is one of those turnarounds. Before Bobby Bowden took over in 1976, the Seminoles won four games during the three previous seasons, going 0-11 in 1973.

Bowden coached Florida State to 14 consecutive top-five rankings, recorded 11 straight bowl victories and two national titles.

Down state in Miami, a similar awakening occurred. The Hurricanes had only two winning seasons in the 1970s. Then Howard Schnellenberger took control in 1979.

He turned the Hurricanes into national champions in 1983, the beginning to a dominant era that included four more titles under three other coaches. The last championship came in 2001 under Larry Coker.

Texas A&M’s Dennis Franchione has a reputation as a program-changer.

Franchione took over New Mexico, which is now in the Mountain West Conference, before the 1992 season.

Before his arrival, the Lobos had won nine games during five seasons, and even went 0-11 in 1987. In Franchione’s second season, New Mexico posted its first winning record (6-5) in 11 years. In 1997, the Lobos went 9-4 and won the Mountain Division of the Western Athletic Conference.

Franchione continued on to Texas Christian, now also in the Mountain West, as well as Alabama and Texas A&M.

TCU was 1-10 in 1997 the year before he came onboard, and two years later became WAC co-champions and then repeated the following season. Even tradition-rich Alabama was coming off a 3-8 record in 2000 when Franchione assumed control. The Crimson Tide went 7-5 in his first season and 10-3 in his second.

Texas A&M, already a moderately successful program, hasn’t been quite as pleasant of an experience for Franchione, but he finished 9-4 last season for his best record in four seasons there.

“I’ve taken over a number of programs that have been down,” Franchione said. “Lack of discipline, lack of accountability, lack of work ethic generally happen where you need a turnaround. These things play into how you recruit players who will last and stay four years.”

The search for quality recruits took New Mexico’s coaches to such faraway locations as Lovington, N.M. There, they came upon a player missing from the other schools’ recruiting lists, but one who seemed promising nonetheless. Now, Brian Urlacher plays for the Chicago Bears and is one of the NFL’s fiercest linebackers.

“People always say recruiting is the key,” Franchione said. “But I’ve always said evaluating is the key.”

While Franchione is known for finding ways to win quickly, other coaches have required more time. Schiano’s first winning record came in his fifth season. Former Iowa State coach Dan McCarney opened his stint with five losing seasons in a row before going on a run of five bowl appearances in six years.

And Wake Forest’s Jim Grobe stood on the sidelines for three successive losing seasons, and five years overall, before last year’s 11-3 record, Atlantic Coast Conference championship and trip to the Orange Bowl.

Grobe said he did not believe in the “quick fix” of signing junior college transfers or going after top high school players with questionable backgrounds.

“If you don’t recruit the right kind of kid and the right character, he’s going to do something stupid and get kicked out of school,” Grobe said. “If he doesn’t have the academics, he’s going to flunk out of school.

“If you get a good football player who’s a good kid, he could turn out to be a great football player.”

Coaches, Grobe said, need a clear understanding of where a program stands when they walk into the football office. He went to Wake Forest knowing that winning the ACC would take time and patience.

Fortunately for Grobe, athletic director Ron Wellman possessed the same understanding about reaching the top of the league.

“We’d love to have done that our first year, but that wasn’t realistic,” Grobe said. “We understood it wasn’t going to happen overnight.”

UNLV Football