New coach Bobby Hauck has big mountain to climb to get program out of doldrums

MISSOULA, Mont.

The "M" hovers over the University of Montana’s football stadium like a protective eagle, but the letter is nowhere to be seen from the base of Mount Sentinel.

It remains out of sight for most of the zig-zag and sometimes treacherous hike over rocks, pebbles and ice that cover a seemingly never-ending 35-degree climb. Only at 620 feet above the stadium is the "M" visible.

It’s not an easy climb, as many a Montana football player discovered.

Breaking one of coach Bobby Hauck’s team rules — one of the minor ones, at least — such as being late for a meeting or practice meant an early morning run up to the ”M.”

The guilty player met a Grizzlies assistant, usually his position coach, at 6 a.m., and the clock started ticking. Make it to the ”M,” shine a flashlight back to the base, then make the trek down the mountain all in 30 minutes — or repeat the punishment.

The penalty underscores the attention to discipline that Hauck believes is at the core of being successful. And it’s that kind of detail Hauck, who was hired last month to revive UNLV’s struggling football program, promises to instill throughout the program.

But as the early morning run to the "M" shows, discipline is handled out of public view. To the media and fans, Hauck will support his players while, in private, he kicks their butts.

The one person Montana players didn’t want to see after committing an infraction was Hauck, athletic director Jim O’Day said.

The punishment would leave "a true, lasting impression on each and every one of them," O’Day said, "and rarely would you see them make the same mistake twice."

TRIBUTE TO TOUGHNESS

Hauck’s record — the eye-popping 80-17 mark, with seven Big Sky Conference championships and three appearances in seven seasons in the Football Championship Subdivision national title game — is remarkable. At any level.

Pete Carroll went 97-19 in nine seasons at Southern California, an 83.6 winning percentage just slightly higher than Hauck’s 82.5.

But many of Montana’s victories didn’t come easy. Last season, the 14-1 Grizzlies overcame deficits in 11 games, their only loss in the national title game. They won five games by a touchdown or less, a tribute to toughness and discipline and perhaps a few of those runs to the "M."

"A trademark of those teams was our ability to win in the fourth quarter," Hauck said. "We work on finishing games, which begins with finishing plays, finishing drills, finishing quarters. It was ingrained in them to finish games, and hopefully we can make that part of the fabric of our football team here."

University of Nevada, Las Vegas fans would love to make beating the University of Nevada, Reno part of the fabric, too. The Wolf Pack has won the past five meetings.

Hauck knows what it’s like to turn around an in-state rivalry. After dropping two of the first three meetings with Montana State, he won his last four.

A Montana graduate, Hauck simply called the Grizzlies’ archrival "State."

"He didn’t think they were good enough to have ‘Montana’ in their name," said Austin Mullins, a Grizzlies senior defensive tackle last season.

Hauck also refused to stay in Bozeman when the Grizzlies played at Montana State, opting instead to lodge 25 miles away in Livingston.

But beating Montana State went beyond mind games. Hauck fielded better teams. Recruiting superior talent will be his first step in trying to halt the Rebels’ skid against UNR.

"That’s how you get it done," Hauck said.

PROTECTING PLAYERS

Born in Missoula and raised in Big Timber (population 1,800), Hauck defines a Montanan. He played three sports at Sweet Grass High School in Big Timber and — too small to play college football — he lettered twice in track at Montana.

If anyone would seem to be a natural fit to become the Grizzlies’ football coach, it was Hauck. Problem was, in 2003, he wasn’t the favorite to become Montana’s coach, not at 38 years old and without ever having been an offensive or defensive coordinator. And he was following a string of successful coaches who had established a Mount Everest-high bar. Hauck had the added burden of succeeding the enormously popular Joe Glenn.

Glenn told jokes, played piano, and could walk into one of Missoula’s four primary downtown bars and know the regular customers and buy them drinks.

Hauck didn’t hang out in bars, and didn’t want his coaches to, either, often inviting them to relax at his home.

"Everybody’s got enough friends," he said. "When you talk about long-term stability and long-term consistent success, you need a coach. It’s not a popularity contest; it’s running a football program."

But for some Montana fans, that wasn’t good enough. They saw only a stern figure on the sideline, someone who tried to protect his players from the media and outside influences.

"We never learned anything outside the very narrow boundaries of Quarterback Club from Mr. Hauck," said Bill Bouchee, a former bank chief executive officer whose son was on the 1995 national championship team. "We had a lot of people drop out of Quarterback Club, because they don’t see it as being useful because Bobby would not tell them information."

Shane Kelly, a bartender at The Missoula Club the past 12 years, said Hauck also didn’t help himself by being so upfront about wanting a job with a major college football team.

"I couldn’t believe that he said it, and it didn’t go over too well," Kelly said.

Hauck did open up over time, showing a warmer side his family and friends long knew existed.

"He likes to have fun. But when it comes to work, people see the serious side, and everything is done the way he wants it to get done, and he’s very well organized," said Hauck’s brother, Tim, who played in the NFL for 13 seasons and is the secondary coach for the Tennessee Titans. "The perception is he’s always serious."

Hauck is highly protective when it comes to his family and friends. So protective that he would not allow his wife, Stacey, to be interviewed for this story.

"He’s hard to read if you don’t get a chance to sit down and talk to him," said Bryan Tripp, a former Montana player whose son, Jordan, was a freshman linebacker last season. "A lot of people never understood because they … see a guy who didn’t want to talk to the media. It wasn’t that he didn’t want to talk to the media. He just didn’t want to talk about things he had no business talking about."

Tripp said the death of Hauck’s father, Bob Sr., nearly two years ago of a heart attack prompted Hauck to open up a bit.

In Hauck’s eulogy, he talked about how his dad, a former coach and administrator, would visit his office on the morning of game days, and about how important family was to Bob Sr. Many of the 1,000 in attendance were in tears, and they gave Hauck a standing ovation.

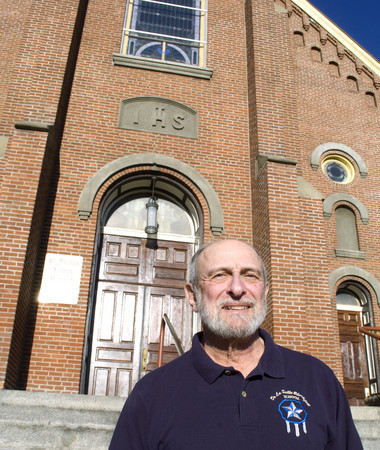

"It was absolutely amazing, absolutely stunning," said Father Rich Perry, pastor at St. Francis Xavier Church, where Hauck, his wife, three daughters and son attended Mass every Sunday. "I told him afterward, ‘Your dad would be very, very proud of you.’"

The crowd’s reaction still moves Hauck, who called it "as proud as I’ve ever been of anything I’ve ever done," noting the eulogy also was "one of the more difficult things I’ve done."

"My father and his father were probably the two best people I’ve ever known," Hauck said. "When I see shortcomings in myself, it’s because I’m not enough like them."

That strong bond with family is why Hauck, even when he works 16-hour days, makes sure he doesn’t sleep in the office and is heading home by 10 p.m.

Fly-fishing on Friday mornings before games also was a perfect getaway. Even then, Hauck couldn’t completely lose his competitive edge, wanting to catch more than his fishing buddies.

"People that are truly competitive never lose that," said David Paoli, one of those fishing pals.

But Villanova coach Andy Talley told Hauck two years ago that life wasn’t all about football. Talley knew from experience; his perspective changed after a heart attack in 2002. This past season, Talley’s Wildcats beat Hauck’s Grizzlies for the FCS national title.

"You need to be able to not have a heart attack at age 50," Hauck said. "You need to be able to put it away and say, ‘I need a hobby.’"

POSSESSION-STYLE OFFENSE

Hauck developed his own coaching philosophy while taking ideas of his mentors as a defensive assistant coach at Montana (1988 to 1989), Northern Arizona (1993 to 1994), Colorado (1995 to 1998) and Washington (1999 to 2002).

His father, a longtime high school coach in Big Timber, provided the love of sports.

"We grew up in the locker room and on the field, track and basketball court," Tim Hauck said.

Current UCLA coach Rick Neuheisel, former Bruins coach Terry Donahue and former Montana coach Don Read influenced Hauck. And even though he never worked under former Washington coach Don James, it was from him that Hauck learned the importance of being "hard-nosed and disciplined," Tim Hauck said.

Hauck made a name for himself under Neuheisel as a top recruiter and assistant at Colorado and Washington before becoming the Grizzlies’ head coach. Coaching on defense allowed him to see the value in emphasizing a balanced offense that controls the clock and keeps the defense fresh.

"One of the best defenses is having an offense on the field," said UNLV linebackers coach Ty Gregorak, who played for Hauck at Colorado and coached under him the past seven seasons. Hauck "loves a powerful, strong running game."

The Grizzlies averaged 160.2 yards rushing per game last season, tops in the Big Sky Conference. They also led the league in scoring offense (35.8-point average) and scoring defense (19.0). In comparison, UNLV’s averaged 126.8 yards rushing per game, scored 24.8 points per game and gave up 32.4 per game.

Hauck’s ground-based attack is an old-fashioned answer to the growth of wide-open spread offenses, which UNLV ran for five seasons under coach Mike Sanford.

The possession-style offense requires a physical and disciplined unit with the willingness to outmuscle defenders.

That toughness at Montana largely was built at the "M" and in twice-a-week winter conditioning workouts that began at 5:30 a.m., something Mullins said the Rebels better get used to in the offseason.

"It’s very regimented, and everything has to be done perfectly, or you’re doing it again," he said. "It’s definitely not easy. Let’s just say there are a lot of trash cans put out in case anyone needs to use one."

JOB-WINNING INTERVIEW

Even as an assistant under Neuheisel, the always-prepared Hauck knew how to sell. When Neuheisel needed to close the deal on a recruit, he sent in Hauck.

So when Hauck had to sell himself in an interview for the Montana position, he had a plan. Two other candidates were Brian Kelly (now Notre Dame’s coach) and Robin Pflugrad (now Montana’s head man).

Then-athletic director Wayne Hogan, sports information director Dave Guffey and Paoli, an attorney and former Montana player and later Hauck’s fishing buddy, interviewed Hauck in Seattle, where he was the Huskies’ defensive backs coach.

"It was probably the best interview I ever sat through," said Hogan, now Georgia Tech’s associate athletic director for public relations.

Hogan said Hauck "absolutely blew me away" by explaining in detail how he would contact recruits and arrange visits, what his practices would be like, how he would instill discipline, and how his coaching staff would be assembled. Hauck even provided names and résumés, and said he already had contacted potential assistants.

"I knew he would win games," Hogan said. "I knew he would be able to recruit."

Hauck also won the UNLV job with his interview, specifically laying out his plan for the entire calendar year much like he did when he applied for the Montana job.

"There was a lot of thought that went into it," UNLV athletic director Jim Livengood said. "He didn’t leave anything to chance."

OFF-FIELD INCIDENTS

From the beginning, Hauck took control of the Montana program, learning class schedules and having assistant coaches make sure players actually were in class. When they weren’t, they had a date with the "M." Players quickly learned the importance of being students.

Diligence and discipline paid off for some Grizzlies. Last semester, the football team had a 2.89 cumulative grade-point average. Four players earned straight-A’s, and 47 of 92 players on the roster had GPAs of at least 3.0.

But Hauck’s handling of discipline regarding off-the-field incidents tarnished his and Montana’s reputation for many. At least eight players were arrested and charged with various crimes in 2007 and 2008, including one for murder (he later was acquitted) and three for a home invasion plus a fourth previously kicked off the team for another offense.

Hauck’s supporters point out that, other than that difficult stretch, most of his tenure was incident-free.

Players charged with felonies never played again for Hauck, who said "sometimes public perception" of how disciplinary matters were handled was "not correct."

The issue of how Hauck handled these off-the-field incidents boiled over this past season and launched Hauck into the national sports spotlight — in a negative light.

The Kaimin, the student newspaper, reported that two cornerbacks were involved in an assault, an allegation where eventually no charges were filed. The story and following questions by Kaimin beat writer Tyson Alger so incensed Hauck, the coach and players refused to answer any questions asked by Kaimin staff for more than a month.

Members of the national media called Hauck a "bum," "a bully" and "egotistical." Athletic director O’Day stood by his embattled coach.

O’Day said Hauck handled the matter correctly by taking away playing time from the players involved while trying to keep the matter private.

"He got his message across to each and every (player) without embarrassing them publicly," O’Day said. "He could’ve just as easily ignored it, and it would never have come to light."

Upon his return from Europe, university president George Dennison didn’t believe he needed to say anything to Hauck. "He made it pretty clear he had learned from it," Dennison said.

But what if a similar situation arises with UNLV’s student paper, The Rebel Yell? How would Hauck handle it?

"Maybe not different," Hauck said, "but I don’t know the answer to that."

STADIUM SOLD OUT

On Grizzly game days, bartender Shane Kelly arrives at 5:30 a.m. at what locals call The Mo Club in downtown Missoula to prepare for fans who begin to arrive at 8 a.m.

Missoula has about 107,000 residents, but the 25,000-seat stadium is sold out each game. About 20,000 season tickets are sold each year to fans from as far east as Sidney, Mont., a 650-mile one-way drive.

It’s a fan base that expects to win, and usually gets it wish. Hauck’s largest sin in the eyes of some is not winning a national championship as two of his predecessors did, including Glenn in 2001.

Expectations are considerably lower at UNLV, which hasn’t had a winning season since 2000. But Glenn said Montana "can be a harder deal. You get the keys to a new car, and you’re scared because you don’t want to wreck it. You’re someone’s Super Bowl every week."

Hauck’s supporters said it was a matter of time before he moved up to college football’s highest level. Now it’s up to Hauck to show he can win in victory-starved Las Vegas.

"That place," Hauck said of Montana, "in terms of the pressure, the scrutiny, the intensity of the competition — I go back to the need-to-win games there — that’s great on-the-job training for any school in the country."

One of Hauck’s immediate challenges is to create the Rebels’ version of the run to the "M."

"No one likes being punitive," Hauck said. "It’s our least favorite thing as coaches, but I’m a firm believer in doing that early in the morning because it’s hard for guys, and it sends a reminder. And we’ll have something. It’ll be something that makes a point to our players."

Contact reporter Mark Anderson at manderson @reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2914.