Legendary UNLV basketball coach Jerry Tarkanian dies at 84

Jerry Tarkanian loved a good fight.

It could be on the basketball court matching wits with Bob Knight, Mike Krzyzewski, Lute Olson or John Thompson. Or it could be in a courtroom taking on the NCAA with a boatload of lawyers in tow.

Tarkanian wasn’t the type to back down, and he always scrapped and fought. Even when his health failed him in the latter years of his remarkable life, he showed a willingness to fight in a hospital intensive care unit.

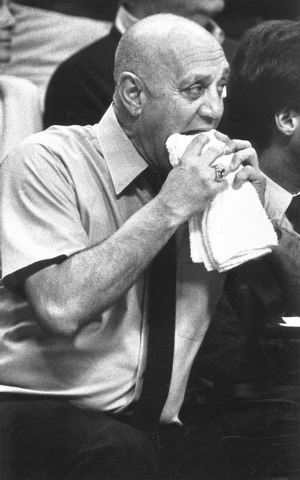

Tarkanian, the iconic towel-chomping coach who put UNLV on the map as a national college basketball power and repeatedly clashed with the NCAA during his career, died from respiratory and cardiac failure at 9:05 a.m. Wednesday at Valley Hospital Medical Center. He was 84.

In a statement issued by the Tarkanian family, his wife, Lois, said: “Jerry has been in fragile health since 2009. He fought his health problems with the same tenacity he showed throughout his life. Our family thanks, from the bottom of our hearts, all those who have sent letters and prayers, who have shown their love for Jerry and support for our family, the numerous fans and the many players who considered him a second father. Our hearts are broken but filled with incredible memories.”

Tarkanian had been recovering from a nearly monthlong stay in the hospital and was getting his strength back, Lois Tarkanian said of her husband of 60 years.

On Sunday, he was home, resting, watching basketball on TV and even making plans to attend Tuesday night’s Fresno State-UNLV game at the Thomas & Mack Center.

But on Monday morning, Tarkanian began having trouble breathing. His blood pressure had dropped to a dangerous level, and he was rushed to Valley, where doctors had managed to keep him alive in previous visits. He was unresponsive throughout the day in the intensive care unit and into the early evening until doctors were able to get his blood pressure elevated. He suffered a setback in the early morning hours Tuesday and was in critical condition.

A private funeral will be Monday. A public memorial service will be held March 1 at the Thomas & Mack Center at a time to be determined.

‘THERE WAS ONLY ONE TARK’

Tarkanian, a 2013 inductee into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield, Mass., coached 31 years on the Division I level at Long Beach State, UNLV and Fresno State and finished his career with a 784-202 record. In his 19-year run with UNLV, from 1973 to 1992, Tarkanian went 509-105 for an .829 winning percentage. He took the Rebels to the Final Four four times, winning the NCAA title in 1990, the only one the program has ever won.

“He was like a second father to me,” former UNLV star Larry Johnson said in 2013 when Tarkanian was inducted into the Hall of Fame. “I loved that man.”

Greg Anthony, Johnson’s teammate from 1989 to 1991, echoed similar comments at the induction, saying: “Some of us didn’t have fathers. But Coach Tarkanian’s door was always open. You could talk to him about anything.”

Dave Rice, the Rebels’ head coach who played for Tarkanian and later coached under him, said: “The qualities that make UNLV a great university — opportunity, self-determination and equality — are the same qualities that Coach Tarkanian ingrained in his teams. The impact of Coach’s contributions to our university, our community, his players and all of college basketball are immeasurable.”

Former UNLV athletic director Brad Rothermel, who worked with Tarkanian from 1981 to 1990, said Tuesday: “There wasn’t an individual who gave us more recognition as a university than Jerry Tarkanian. He took us from Tumbleweed Tech, a small college in the desert nobody had ever heard of, to a nationally known institution.”

Mark Warkentien, who worked as an assistant under Tarkanian from 1981 to 1987, said of his former boss: “There was only one Tark. A coach who could show Las Vegas how to win and make the NCAA a tighter ship.”

Tarkanian had success at virtually every stop during a coaching career that spanned five decades. But it was at UNLV where he achieved the most success.

Thirty-nine of his players were drafted by NBA teams, nine in the first round. Johnson was the No. 1 overall pick in the 1991 draft, selected by the Charlotte Hornets, and Armon Gilliam was the No. 2 overall pick in the 1987 draft by the Phoenix Suns.

That success landed Tarkanian a spot among the basketball elite in Springfield. Despite his failing health and inability to carry on a lengthy conversation, Tarkanian enjoyed the induction weekend, during which he was given a lengthy standing ovation at the ceremonies.

“This is wonderful,” he said. “This is a great honor, and I’m very grateful to the Hall of Fame. I’m glad my family was able to enjoy it with me.”

Tarkanian’s contributions to basketball still can be found today. His defensive pressing style. His up-tempo offense. His effective use of the 3-point shot. His ability to relate and communicate with African-American players.

Those elements are used by many of today’s college coaches.

“The first thing we need to remember about Jerry is what he brought to the game of basketball,” Rothermel said. “He was the first to employ a full-court defense combined with a fast-break offense. Some schools had one or the other but not both. He helped change the way basketball was played and is still played today.”

OFF AND RUNNIN’

Tarkanian was born the son of Armenian immigrants on Aug. 8, 1930, in Euclid, Ohio. His relationship with basketball began as a player at Pasadena City College in California. He transferred to Fresno State in 1954 and played two years before graduating in 1955.

His coaching career began at the high school level. But unlike most in his profession, Tarkanian never served as an assistant coach. He always was a head coach.

After stints at three high schools, Tarkanian moved to the junior college level in 1961, becoming Riverside City College’s head coach. His teams won three straight California junior college titles.

From there, he went back to Pasadena City College, where he coached for two years before he was named the head coach at Long Beach State.

It was with the 49ers that he had his first run-in with the NCAA. He questioned UCLA’s pristine image under coach John Wooden in a newspaper column he wrote for the Long Beach Press-Telegram, and eventually the NCAA came to Long Beach State to investigate Tarkanian’s program.

By the time the NCAA was through with its investigation, Tarkanian was gone. He had been approached by a group of boosters from Las Vegas in 1972 to come to UNLV. Initially, he rejected their offer but reconsidered after the 1972-73 season and accepted the school’s head coaching position.

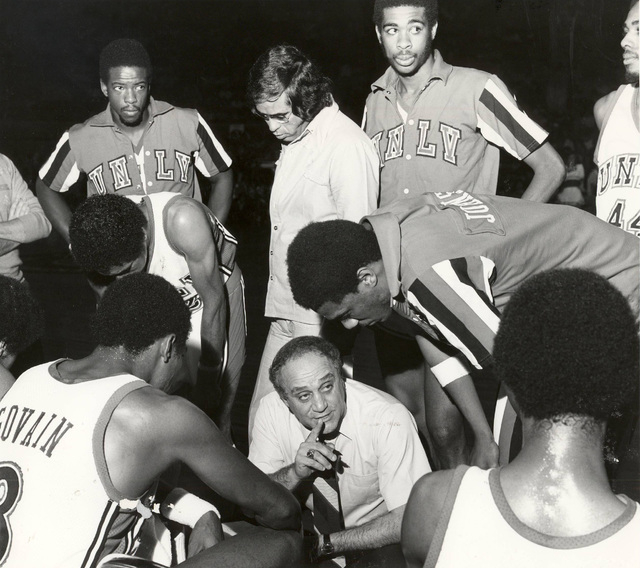

At the time, the Rebels were playing in the rotunda at the Las Vegas Convention Center. They were in the West Coast Athletic Conference and had played a deliberate style of basketball under then-coach John Bayer.

In Tarkanian, the boosters were hoping to see a more up-tempo offense, one that would get crowds excited and generate more donations to the university, as it was looking to build an on-campus basketball arena.

Tarkanian delivered. With deft recruiting, he signed much more athletic players. The Rebels used pressure defense to force turnovers and easy baskets. Suddenly, they were pushing the ball on offense and blowing out teams.

But his first game at UNLV did not go well. His team lost to Texas Tech 82-76, and Tarkanian went on the postgame radio show and said he wouldn’t be surprised if he were fired, given the lofty expectations attached to his arrival.

That wouldn’t happen for 19 years.

His first Rebels team went 20-6. In 1975, UNLV made its first-ever NCAA Division I Tournament appearance, going 24-5 and losing to Arizona State in the second round.

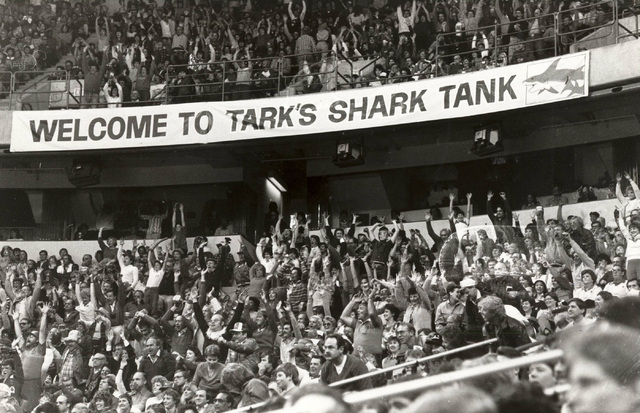

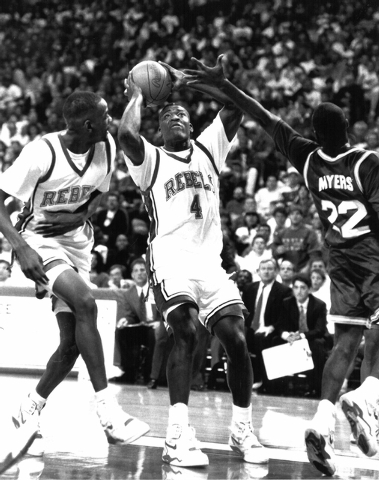

The team was dubbed the “Runnin’ Rebels” because it was up-tempo and posted triple-digit scores. Tarkanian was known as “Tark the Shark,” as fans embraced his style and his players’ flair.

“We had to play that way because of the kids we had,” Tarkanian said years ago in a documentary about the program. “We didn’t have a lot of size. But we had great athletes, and we used our speed and quickness.”

NATIONAL SPOTLIGHT, AND NCAA SCRUTINY

By 1977, the Rebels had become a national power, and after beating San Francisco, Utah and Idaho State in the NCAA Tournament, Tarkanian was in his first Final Four.

That team, known as “The Hardway Eight” because he played a short rotation, faced North Carolina in the national semifinals at the Omni in Atlanta. The Rebels, who averaged 109 points that season, struggled against the Tar Heels, who employed coach Dean Smith’s famous “Four Corners” offense and defeated UNLV 84-83.

At that point, kids from all over the country wanted to be part of the Rebels’ fast-paced style of play and coached by Tarkanian, who had a reputation for giving his players freedom on offense provided they worked hard on defense.

Tarkanian had become a celebrity. He rubbed elbows with the likes of Frank Sinatra, and a ticket to a UNLV game became the most sought-after in Las Vegas.

Tarkanian would later use his celebrity to make it to the big screen. He appeared in the 1992 movie “Honeymoon in Vegas” as poker player Sid Feder, and he played himself as a coach in the 1994 basketball movie “Blue Chips.” In 2011, HBO did a documentary on Tarkanian and the UNLV basketball program — “Runnin’ Rebels of UNLV.”

Still, despite landing some excellent players, including future NBA star Sidney Green, UNLV would not return to the Final Four for another 10 years.

Meanwhile, Tarkanian’s battles with the NCAA were heating up. Just before the 1976-77 season, the NCAA placed UNLV on probation for two years, and the university was to suspend Tarkanian from coaching during that period. But he sued the NCAA, claiming he had been denied his rights as an American citizen under due process.

That case eventually went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in 1988 ruled the NCAA, as a private voluntary organization, had the right to discipline its members. But it also ruled that Tarkanian was entitled to a proper hearing and that his due process rights had been violated.

In 1998, the NCAA and Tarkanian finally settled their differences. Tarkanian, who was coaching Fresno State at that point, was awarded $2.5 million, and while he was happy with the result, he was bitter at what he had to go through to win his case.

“It wasn’t worth it, everything I went through,” he said after the settlement.

On the court, UNLV continued to enjoy success. In 1982, while still playing at the Las Vegas Convention Center, the Rebels became part of the Pacific Coast Athletic Association after a failed attempt to join the Western Athletic Conference in 1981. The PCAA, later the Big West, would be dominated by Tarkanian’s teams throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s.

Buoyed by a renewed success at recruiting and with the support of Rothermel, his new athletic director, and assistant coach Tim Grgurich, who had previously been the head coach at Pittsburgh, Tarkanian guided UNLV back into the NCAA postseason.

In 1983-84, the Rebels went 29-6 as they christened their new home — the 18,500-seat Thomas & Mack Center, which was built on-campus and would become a house of horrors for opposing teams. In 1986, the Rebels returned to the Sweet 16 and finished 33-5, then a school record for most wins in a season.

That set the stage for UNLV’s second Final Four appearance. The 1987 team won 37 games and was a mix of an aggressive defense and deadly perimeter shooting. But the Rebels fell short in the national semifinals at the Superdome in New Orleans, losing to eventual national champion Indiana 97-93.

It was around that time that Tarkanian and the NCAA were about to butt heads again. This time, it was over the recruitment of Lloyd Daniels, a New York schoolyard prodigy who the NCAA alleged received extra benefits to attend UNLV.

Daniels was busted in a North Las Vegas crack house for trying to sell drugs and never played for UNLV. But the NCAA didn’t back off, and the school, under new president Robert Maxson, did not back its coach this time.

REBELS’ RISE, FALL AND FIXING ALLEGATIONS

While the NCAA was continuing its investigation, UNLV remained eligible for postseason play. In 1989, it reached the West Regional finals, losing to Seton Hall.

But the following year, with the addition of Johnson, a junior college All-American, joining Anthony, Stacey Augmon and Anderson Hunt, Tarkanian had the kind of team he thought could win the national championship.

The 1990 UNLV team was not perfect. It lost conference games at New Mexico State and UC Santa Barbara. Anthony, the indispensable point guard, had broken his jaw in early February against Fresno State.

But the team got hot at the right time.

It survived a scare in the West Regional semifinals, edging Ball State 69-67. In the final, UNLV blew out high-scoring Loyola Marymount 131-101 to reach the Final Four for the third time in Tarkanian’s UNLV tenure.

This time, things would be different. In the national semifinals in Denver, the Rebels rallied from seven points down at halftime to beat Georgia Tech 90-81 and earn a spot in the national championship game against Duke.

In the final, UNLV led early on, built its lead and then blew out Duke in the second half, winning 103-73, the largest margin of victory in an NCAA title game.

But the NCAA was prepared to not let Tarkanian celebrate for long. The plan was to prevent the program from defending its title in 1991. But the school negotiated a deal with the NCAA that would allow the team to play in the tournament that year in exchange for no postseason in 1992.

Johnson and Augmon returned for their senior seasons. UNLV, the No. 1 team in the country in The Associated Press and United Press International polls, went undefeated, taking a 34-0 record into the Final Four at Indianapolis, where a rematch with Duke awaited the Rebels.

And while heavily favored to repeat, the Rebels were blindsided by an aggressive Duke defense. Anthony fouled out with less than five minutes remaining, and with their point guard on the bench, UNLV struggled offensively.

In the end, Duke pulled one of college basketball’s biggest upsets ever, defeating UNLV 79-77 and ending its dream of back-to-back national titles.

Almost immediately after the game, allegations surfaced that some UNLV players might have been shaving points.

The allegations were never proved, but a cloud hung over the program, one that intensified when a photograph in the Review-Journal in May 1991 showed UNLV players in a hot tub with Richard Perry, a convicted sports fixer.

Tarkanian said he had no knowledge of the association between Perry and players Moses Scurry, David Butler and Anderson Hunt. But the school’s administration had seen enough, and ultimately it was decided that Tarkanian would resign after the 1992 season.

His final team went 26-2 but had no postseason to look forward to because of the deal it made with the NCAA. So UNLV went to court, looking for relief and a chance to rescind the ruling. It was denied.

LIFE AFTER UNLV

Tarkanian, who had turned down several offers during his UNLV tenure to coach in the NBA, including the Los Angeles Lakers in 1977, moved on. He became the coach of the San Antonio Spurs in late spring 1992 despite having no experience at the pro level.

Ironically, he was reunited in San Antonio with Daniels, who was a free agent trying to save his career. But their association didn’t last long. Tarkanian clashed with general manager Bob Bass and was fired in December 1992 with a 9-11 record.

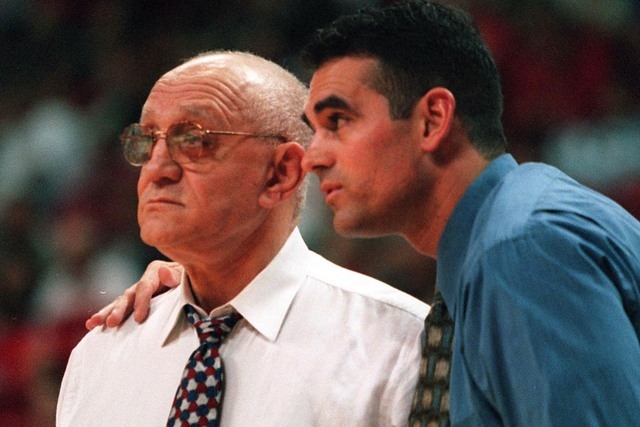

In 1995, Tarkanian got the itch to coach again. And again, boosters approached him, this time from Fresno State, his alma mater.

He accepted the job and brought son Danny with him as an assistant coach. He was 153-80 in seven seasons at Fresno and went to two NCAA Tournaments, never making it out of the second round.

But as was the case at Long Beach State and UNLV, Tarkanian fought with the NCAA. After his retirement in 2002, Fresno State was placed on probation for violations committed under his watch, though he never was implicated.

Tarkanian never returned to the sidelines. He spent his retirement shuttling between Las Vegas, Fresno and San Diego, where he owned a summer home. He was a frequent visitor to the Del Mar Race Track, though he rarely bet on the horses.

HALL OF FAME INDUCTION

When the Southern Nevada Sports Hall of Fame was in its infancy, Tarkanian was one of its early honorees, going into the organization’s second class in 1998 with his 1977 Final Four team. It would be the start of several local and national honors Tarkanian would receive.

In 2005, UNLV named the floor at the Thomas & Mack Center “Jerry Tarkanian Court.” He had been coming to games regularly since 2001, when then-coach Charlie Spoonhour asked him to show up. That courtesy was extended further by Lon Kruger, who took over in 2004. It was Kruger who persuaded then-UNLV president Carol Harter to name the court in Tarkanian’s honor.

His health began failing in 2007. An operation to remove pressure from his spine in 2009 slowed him considerably. He was an occasional visitor to UNLV games and other college basketball events in Las Vegas, preferring to remain in the background.

When he was well enough to attend a UNLV game, his appearance would be noted on the Jumbotron video boards in the Thomas & Mack, which would elicit a standing ovation from fans.

In March 2012, Tarkanian contracted bronchitis, and after a visit to his doctor, an EKG revealed he was in the midst of suffering a mild heart attack. He was admitted to MountainView Hospital, where he spent two nights.

No surgery was required, but it was not Tarkanian’s first heart issue. He had received an angioplasty procedure twice since he had retired from coaching. He also had circulation issues in 2010 that limited his mobility to the point to which he needed assistance to walk.

He was on the ballot for the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame on three occasions but failed to gain the necessary votes for induction. In a 2012 interview, Tarkanian said going into the Hall of Fame would have meant a lot to him.

“It would be nice, not only for me but for all our players and coaches,” he said. “But it would also be nice for my family.”

The call finally came shortly before the 2013 Final Four in Atlanta. After years of trying, Tarkanian was now a member of the Hall of Fame. Among those he was inducted with included college coaching contemporaries and friends Rick Pitino and Guy V. Lewis.

“It’s a real exciting time for me,” Tarkanian said. “I think it validates everything I’ve done in basketball.”

Jerry Colangelo, the chairman of the Hall of Fame, said of Tarkanian’s election: “Time has a way of healing things. And in this case, time worked in his favor.”

Many of Tarkanian’s former players and coaches attended the ceremony in September 2013. He needed assistance to walk to the stage, where he was presented by Hall of Famers Bill Walton and Pete Carril.

In October 2013, UNLV unveiled a life-sized bronze statue of Tarkanian on the plaza adjacent to the Thomas & Mack Center and Cox Pavilion. The statue, which shows Tarkanian chewing on his trademark towel and with the empty “ghost chair” next to him, was made possible through private donations in the community for what is officially known as the “Jerry Tarkanian Legacy Project.”

Tarkanian also was honored by Long Beach State and Fresno State after his Hall of Fame induction. A high school tournament — The Tarkanian Classic — has been played at Bishop Gorman High since 2012 and features some of the nation’s best teams.

HEALTH TROUBLES

His declining health had made it tough for Tarkanian to enjoy all the honors that had been bestowed upon him. A series of small strokes and the heart problems robbed him of his strength, and he could not speak for extended periods. In an eight-month period in 2013 and 2014, he had three stays in the hospital of a week or longer.

Tarkanian was admitted to Valley on April 9 after returning from Dallas for the 2014 Final Four, where he had been a special guest of Kentucky coach John Calipari, whose team lost to Connecticut in the championship game. Tarkanian had suffered a heart attack and contracted pneumonia and spent 10 days in the hospital.

Tarkanian returned to Valley on Nov. 19 after contracting pneumonia. He was released Nov. 24, just in time to celebrate Thanksgiving with his family.

But he suffered a relapse in early December and was admitted to the hospital again, this time for a month before being released Jan. 7.

“He’s a fighter, he really is,” Lois Tarkanian said after her husband returned home following his lengthy stay.

Tarkanian’s death comes just four days after another legendary college basketball coach — North Carolina’s Smith — died after a lengthy illness on Saturday.

Tarkanian is survived by his wife, Lois, a Las Vegas councilwoman; daughters Pamela Tarkanian and Jodie Diamant; sons George and Danny; all of Las Vegas; a sister, Alice; a brother, Myron; both of Pasadena, Calif.; and 11 grandchildren.

In lieu of flowers, the family requests that donations be made to the Jerry Tarkanian Scholarship Fund at UNLV. Donations can be sent to Tark Fund, Box 451010, 4505 S. Maryland Parkway, Las Vegas, NV 89154.

Contact reporter Steve Carp at scarp@reviewjournal.com or 702-387-2913. Follow him on Twitter: @stevecarprj.

RELATED:

Tarkanian gave media plenty to cover — good and bad

Tarkanian changed the game forever

Vegas remembers Jerry Tarkanian — PHOTOS

Delayed but not denied, Tarkanian finally opens door to Basketball Hall

Players, officials, family honor Tarkanian at induction ceremony

Tarkanian: Hall of Fame election ‘validates everything I’ve done’

Tarkanian overwhelmed by overdue election to Basketball Hall of Fame

Bronze statue honors ‘Tark the Shark’ on UNLV campus

Signs of Tarkanian’s innovations all over college game

Tarkanian recalls three matchups against Wooden, UCLA

‘Shark Attack’ author Yaeger holds Tark close to his heart