Rebels in Ruins: As Las Vegas evolves, UNLV’s struggles continue

What goes up must come down is an adage often associated with Sir Isaac Newton, the classic rock band Blood, Sweat & Tears and, more recently, UNLV’s football and basketball teams.

It is based on the laws of gravity and the knowledge that things change over time.

Discounting a brief return to basketball prominence when Lon Kruger was coach, it has been decades since either of the Rebels’ primary sports have been described as on the rise.

As the losses mount amid the advent of major league sports in Las Vegas, the Review-Journal examines UNLV athletics in a five-part series beginning today that focuses on the issues surrounding its revenue-producing programs.

To understand how far UNLV has fallen, one must first recall the heights to which it had ascended.

“For the better part of two decades, from the early 1970s to the early 1990s, the Runnin’ Rebels of UNLV embodied the spirit of the city they represented: brash … bold … swaggering. And dedicated to the notion that winning, and winning big, was all that mattered.”

That is how the Rebels’ basketball team was recalled in the opening montage of the HBO documentary “The Runnin’ Rebels of UNLV.”

It was released in 2011.

Seasons in the sun

It has been 28 seasons since UNLV won the NCAA men’s basketball championship, 27 since they achieved the fourth Final Four berth of Jerry Tarkanian’s tumultuous 19-year run as head coach — a reign that generated 519 victories, 12 NCAA Tournament bids and more controversy than the Iraq invasion of 2003.

It has been even longer since the UNLV football team was relevant.

The Rebels have produced five winning football seasons over the past 30. Their all-time winning percentage of .401 heading into the 2018 season ranked 118th among the NCAA Division I’s 130 football-playing schools.

At most universities, college football pays the athletic department bills. At UNLV, it drains limited resources.

There was a time when the Rebels weren’t the pushovers they are today. The first three coaches in the program’s history retired, stepped down or moved on with winning records. One, the colorful Ron Meyer, became a successful NFL head coach.

During the 1981 season, UNLV upset eighth-ranked Brigham Young and its star quarterback Steve Young. Three years later, the Cougars were crowned national champions.

For at least a little while, the Rebels seemed on their way in football, too.

First-class coaches

Dr. Brad Rothermel, UNLV’s athletic director during much of the period comprising the glory years, said the Rebels’ success during that era is easily explained.

“Jerry Tarkanian and his coaching staff. Harvey Hyde and his coaching staff,” said Rothermel, 80, who resigned as an athletic department consultant in 2016. “Resources obviously. Financial resources are the most important thing, because you can convert those to the other resources you need, including personnel.”

Before the emergence of Power Five and Group of Five conferences and big TV money, the gulf between the NCAA’s haves and have-nots was less pronounced. It was easier to compete for victories and coaches.

The NCAA manual wasn’t as thick. If you wanted to structure a contract in which the basketball coach was promised 10 percent of the gate or a stack of complimentary tickets, you could do it without fear of NCAA reprisal.

But ultimately, Rothermel said, it still came down to X’s and O’s.

“Historically, there have been very few coaching staffs at major universities better than Jerry Tarkanian, Tim Grgurich and Mark Warkentien,” he said of his basketball staff. “We just had awfully good teachers and awfully good recruiters. Harvey was a big-time recruiter. That was one of the reasons I added Harvey.”

Guilt by association

Jerry Tarkanian and Harvey Hyde had been big winners at the junior college level. They were friends and allies at UNLV, their teams espousing the brashness, boldness and swagger.

Entrusted with taking the Rebels to the proverbial next level, UNLV’s two head coaches took risks on talented recruits with suspect academic and social backgrounds.

Many excelled in a structured college environment. Some did not.

“I had kids, like everybody does in a family,” Hyde said. “If you have 120 kids in your family, not all are going to be doctors and lawyers.”

There were NCAA investigations and suspensions. Academic transcripts were scrutinized. Prized basketball recruit Lloyd Daniels was caught on television trying to buy crack cocaine from an undercover police officer.

UNLV president Dr. Robert Maxson, initially a supporter of the basketball and football programs, became the new sheriff in town.

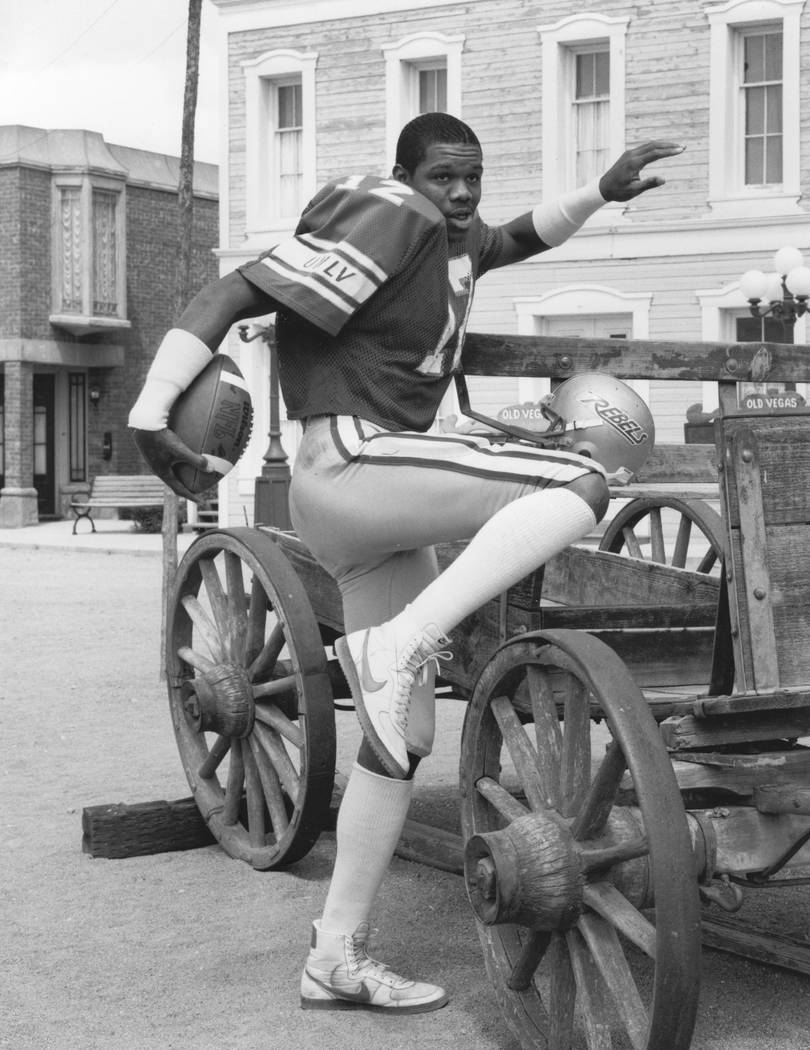

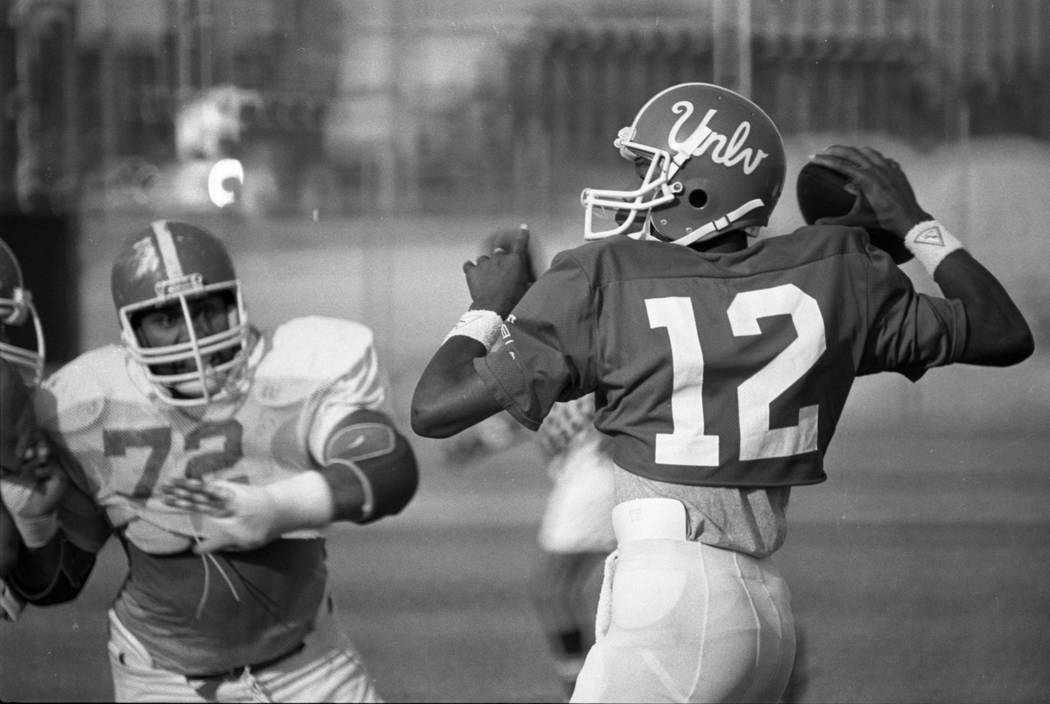

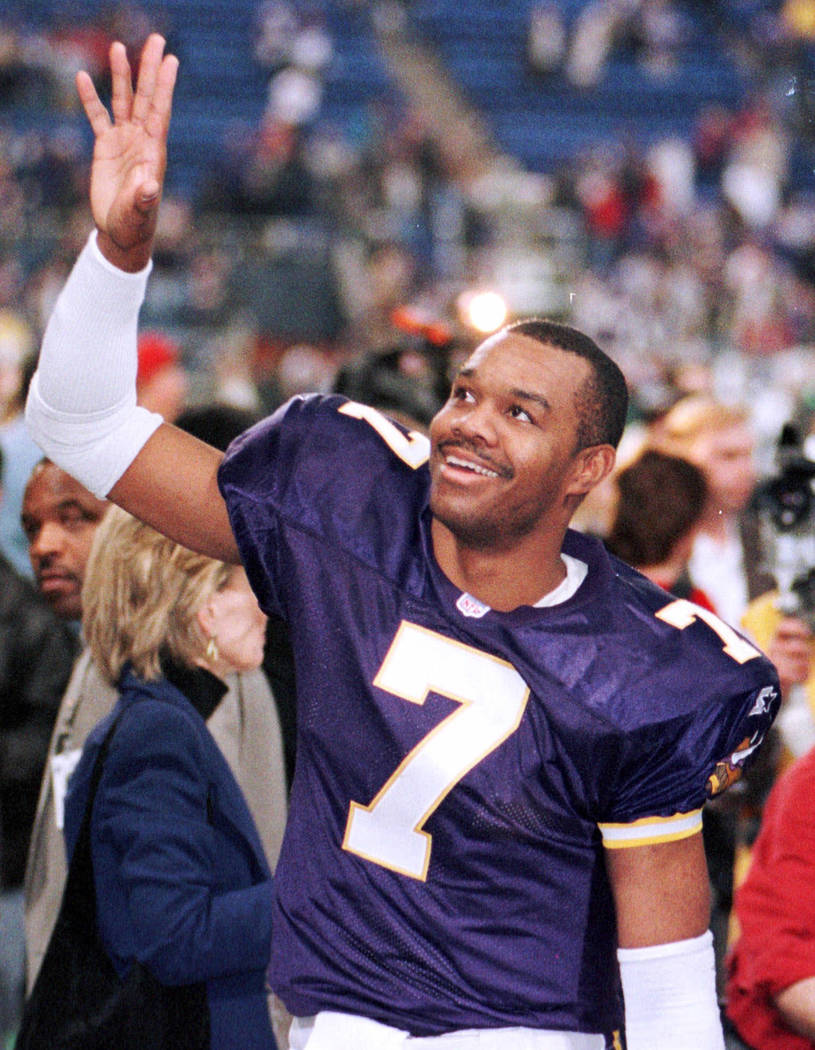

“For some reason, he thought football and basketball were a threat to academics and him,” said Hyde, whose 1984 football team, led by star quarterback Randall Cunningham, went 11-2 and defeated Toledo 30-13 in the California Bowl.

It was the first UNLV team to play in a bowl game.

The Rebels eventually had to forfeit the victory for using ineligible players during the regular season.

UNLV’s firing squad

“Any university knows (athletics) is one of the best marketing tools,” Hyde said. “You have more enrollment when you are doing well in sports. Your alumni are more proud of the school. You have more donations, you sell out your stadium, budgets are better.

“For some reason, (Maxson) had a jealousy toward me and Jerry, and I was the opening act.”

Hyde was fired before the 1986 season. It took Maxson longer to oust Tarkanian after the basketball team reached its zenith by blowing out Duke to win the 1990 NCAA championship.

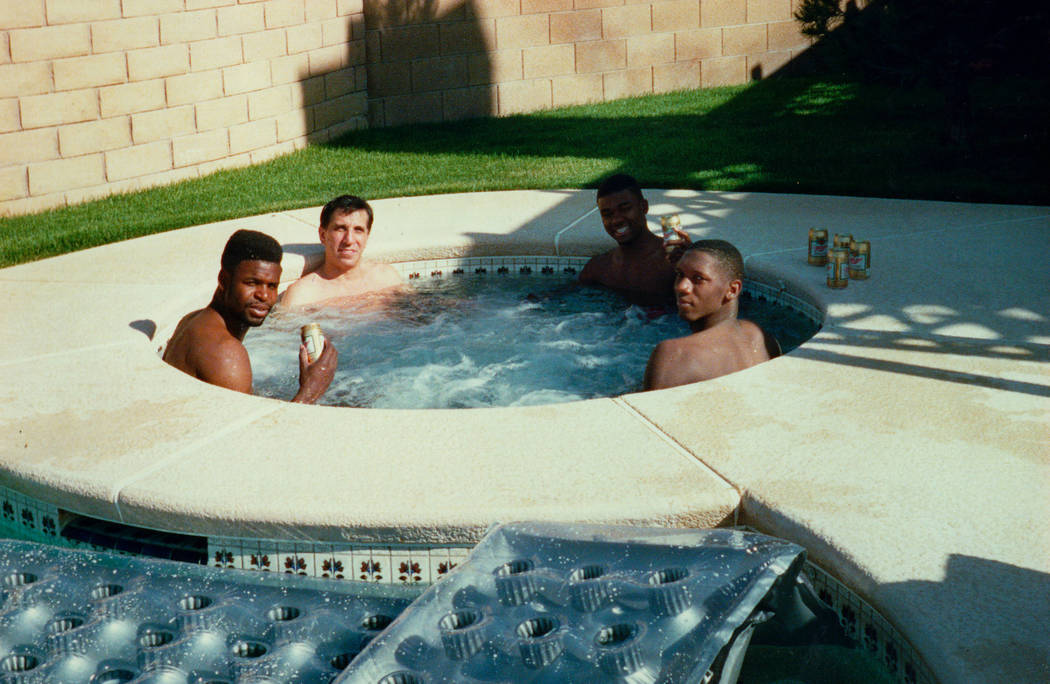

But when a photo showing Rebels players in a hot tub with Richard Perry, a convicted sports fixer, was published in the Review-Journal shortly after undefeated UNLV lost to Duke in the 1991 Final Four, Tarkanian announced his resignation. And then rescinded it.

Athletic director Dennis Finfrock, who had replaced Rothermel when the latter refused to fire Tarkanian, admitted to the placing of cameras in the rafters of the Rebels’ practice gym to film an illegal preseason practice.

It was viewed as Rebel-on-Rebel crime, and UNLV fans were outraged.

Ships go under

In a peculiar twist, Maxson, after leaving UNLV, would become president at Long Beach State, where both Tarkanian and Hyde had coached. He was president of Sierra Nevada College in Incline Village from 2007 to 2010 before retiring. Repeated efforts to reach him were unsuccessful.

Michael Green, a Las Vegas historian and UNLV history professor, said Bob Maxson and Jerry Tarkanian were ships on a collision course.

“And there was no way for them to change course,” Green said. “Yes, there was some machismo involved on both sides. Once they started butting heads, it was not going to end without somebody getting badly damaged. And it turned out it was both of them.”

Rebels fans and benefactors were irreparably damaged in the crossfire. When Tarkanian eventually was forced out, it caused a bitter split between the university and the community from which some believe the athletic department has never fully recovered.

“The community was completely divided,” said Hyde, who remains a staunch supporter of UNLV athletics despite his firing. “(Back then) there wasn’t the Golden Knights or some other thing to go to.

“UNLV was the NFL team, the NBA team. UNLV was everything.”

More Rebels: Follow at reviewjournal.com/Rebels and @RJ_Sports on Twitter.

Ron Kantowski at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow @ronkantowski on Twitter.

REBELS IN RUIN

Read Part 2 of the series in Tuesday’s print edition and online at 6 a.m.