Many southern Nevada residents have ties to Indy 500

After he held off Scott Goodyear to win the 1992 Indianapolis 500 by an eyelash, Al Unser Jr. pulled into Victory Lane and was overcome by emotion.

He had won it by .043 second — still the closest of all the 500-mile races.

Maybe that was it.

Maybe it was “Back Home Again in Indiana,” and “Gentleman Start Your Engines” and Gasoline Alley, and the yard of bricks, and the cold bottle of milk and the myriad other rites and passages of the hallowed Brickyard near downtown Indianapolis that left the second generation driver speechless and choking back tears.

“You just don’t know what Indy means,” Little Al said.

They’ll run number 100 on Sunday.

The centennial observation of the 500-mile speedfest must mean a lot of things to a lot of people — a supercharged horde approaching 400,000 is expected to bear witness to history, and to what everybody is calling the biggest Indy 500 ever.

Southern Nevada will be well represented, beginning at the front of the field.

That’s where Sam Schmidt, the longtime Henderson resident who competed in three Indy 500s before a terrible racing accident rendered him a quadriplegic, finds himself.

Schmidt is now a successful car owner, one of the speedway’s most admired patrons. The fastest of his three entries will start from the pole position. It’ll be driven by James Hinchcliffe, the pleasant Canadian who nearly lost his life after crashing Schmidt’s car in Turn 3 last year.

Others have their own Indy stories to tell.

They are scattered among the rows of three cars, in the pits, in the massive grandstands that have been sold out for months.

They are people who know what Indy means.

THE CREW GUY

A couple of weeks before the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500, Cody Selman was making sandwiches at the Jimmy John’s on West Charleston in Summerlin, just off the 215 Beltway. It is one of two local sandwich shops he owns with his wife, Jamie Little, the Fox TV NASCAR pit road reporter from Las Vegas.

Selman was wearing a hat with Kevin Harvick’s number on it — the NASCAR driver is sponsored by Jimmy John’s. He said the goal of his crew is to serve hungry customers a sandwich with all the trimmings in 30 seconds.

That sounds fast. He’ll have to be faster than that in the famous 500-mile race.

Selman is the left rear tire changer on the Dreyer & Reinbold-Kingdom Racing No. 24 Gas Monkey Chevrolet driven by youngster Sage Karam. A fast pit stop at Indy is less than 10 seconds.

The big race at the Brickyard has always been a family affair for the Selman men, regardless of the efficiency of the pit stops.

Wayne Selman, Cody’s father, started out with two-time Indy winner Al Unser Jr. and the New Mexico-based Galles Racing Team during the early 1990s. Wayne Selman is now the transport manager for Ed Carpenter Racing.

Chase Selman, Cody’s brother, is team manager for Dreyer & Reinbold. Chase Selman, who resides in Indianapolis, is married to Danica Patrick’s sister, Brooke. He’ll change the right rear tire on race day.

Carter Selman, Cody and Jamie’s son, will mostly be a spectator. Carter is 3 years old. Too young to work an airgun. Not too young to have attended every Indy 500 since he was born.

“Just growing up around IndyCar my whole life, it’s always been my favorite form of auto sport,” Cody Selman said. “To be part of the 100th race — there’s so much prestige and honor. I’ve been lucky to go back and be part of it every year since I was 18. That’s a lot of fun.

“Having my family there is just going to make it that much better.”

THE JUDGE

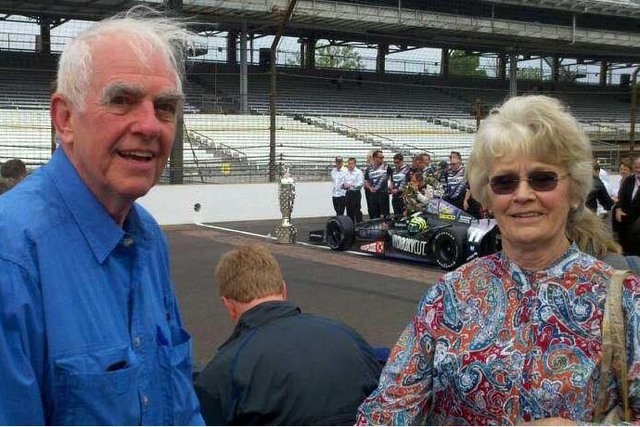

Sometime during the middle of the night before the Indianapolis 500, Justice Court judge Bill Jansen invariably will wake up from a restless sleep in his hotel room not far from the track and check to see if it is raining.

There’s not a darn thing one can do about the rain. Not even a judge. But he’ll have checked for rain anyway, because this is is the 100th running of the famous 500-mile race — his 50th — and they’ve yet to run one when it rains.

“This is the big one,” says the Judge, who as Justice of the Peace presided over the Las Vegas weddings of auto racing luminaries Carroll Shelby, the pioneer car builder, and Ray Evernham, Jeff Gordon’s former NASCAR crew chief. “Fully sold out — 238,000 seats, another 100,000 in the infield.

“They say this will be the biggest crowd ever to attend the 500.”

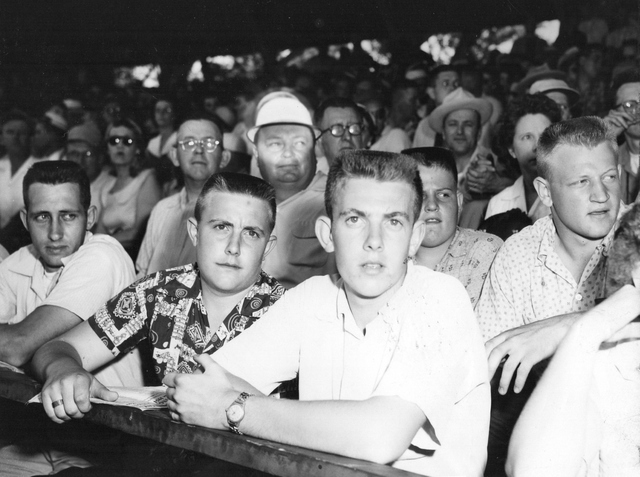

The crowd wasn’t nearly that large when the Judge saw his first 500-mile race in 1949 although to a young boy it may have seemed like it. A guy named Bill Holland won, driving 500 miles in a car called the Blue Crown Special. Bill Jansen, who was 13, rode in a car called a Packard. It had a giant ornament on the hood. It was 211 miles from his boyhood home in Pekin, Illinois, to the speedway.

The grandstands were made of wood. The track was made of bricks.

The Judge has witnessed most of the great ones drive at Indianapolis; his favorites were A.J. Foyt and Bill Vukovich, who won consecutive 500s back in the day of the Blue Crown Special and the Packard, but was killed at Indianapolis while racing toward three in a row.

Bill Jansen, 80, said Ol’ Vuky was a hard man who drove wearing a T-shirt. No fireproof overalls for him. Tony Bettenhausen wore a helmet with cloth ear flaps. Sometimes you’d see the flaps flying in the breeze when he was really on it.

You should have heard the roar of the Novi engine and those four-cylinder Offenhausers, The Judge says.

THE DRIVER

In Jimmy Vasser’s home on Canyon Gate golf course is the big trophy he received for having won the U.S. 500 in 1996. There’s a cup on top.

“It holds about three cans of beer,” Vasser said during a break in practice for the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500.

While there have been 99 runnings of the venerable Indy 500, there were only four U.S. 500s. The first was a result of American open-wheel auto racing splitting into two series. A change in the qualifying rules at Indianapolis meant most of the established teams, who stayed loyal to Championship Auto Racing Teams (CART), were not eligible to compete at Indy.

So the CART teams held their own race at Michigan Speedway on the same day as Indy, and Vasser won it.

“Who needs milk?” he said upon wheeling into the winner’s circle, alluding to one of the Indy 500’s most storied traditions.

Vasser won 10 races during his driving career, and three were 500-milers, and those are the big ones. But he stayed loyal to the CART series. So although those triumphs came against the best teams and drivers, none were at Indianapolis.

He raced in eight Indy 500s, most a little before or a little after his driving prime. He finished fourth twice.

The result is that Jimmy Vasser, now an Indy 500 car owner, is not nearly as famous as he might have been, though those in Gasoline Alley still hold him in high regard.

“I wouldn’t use the word cheated,” said Vasser, 50, who with partner Kevin Kalkhoven will field three cars in Sunday’s race, to be driven by veteran Sebastian Bourdais and rookies Matthew Brabham and Stefan Wilson.

“I won three 500-mile races,” he said. “Unfortunately, they are only 500-mile races in the record book. But I got to drive into Victory Lane; I got my Indy 500 with Tony Kanaan (in 2013).”

When he joined his driver in the winner’s circle for what was a popular victory, he drank the milk.

THE ATTORNEY

It was Tuesday morning, five days before the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500, and Marc Risman, a local attorney, was complaining about Southwest Airlines having inflated its fares from Las Vegas to Indianapolis this year as if they were Firestone racing tires. Hotel rooms are at a premium, too.

Risman said he was able to find a reasonable fare on Allegiant, with the drawback being he couldn’t catch a return flight until Wednesday.

“That’s OK,” he said. “I’ve never been to the victory banquet. And if Scott wins this year, I’d like to be there.”

Scott is Scott Dixon, the 2008 winner of the 500 and one of the best and coolest drivers on the circuit. The New Zealand native has 39 victories over a 15-year career. Only four drivers have more. Their names are Foyt (A.J.), Andretti (Mario and Michael) and Unser (Al Sr.).

Marc Risman has been Scott Dixon’s attorney since 1999, when Dixie, as he is called around Gasoline Alley, was just getting started. Dixon had several financial backers then, but it was a lousy deal for the young driver. Risman, who has represented boxers, was familiar with these types of lousy deals.

He had done legal work for Stefan Johansson, the former Formula One and IndyCar driver who had become Dixon’s manager, and that’s how Risman came to dot the i’s and cross the t’s for Scott Dixon. He also has provided legal aid to Conor Daly (and his racing father Derek) who also will drive in the 100th running of the 500.

Should Dixon cross the yard of bricks first, maybe Risman will be interviewed on New Zealand TV again.

When Dixon won in 2008 and was summoned to take take the traditional victory lap in the pace car, he handed the giant victory laurel to Risman. The New Zealand TV reporters thought Risman must be somebody special, holding the victory wreath like that. So they interviewed him.

“It was amazing,” Marc Risman said of watching his client bask in the glory of winning at Indianapolis. “You saw that smile on Sam Schmidt’s face when (James) Hinchcliffe (Schmidt’s driver) got the pole? That’s what it was like.”

THE DAUGHTER

During the 57th running of the Indianapolis 500 in 1973, a tall driver from California with shaggy blond hair and movie-star looks was leading the Indianapolis 500 when he pitted for fuel. The driver’s name was Swede Savage. He came out of the pits in second place, sandwiched between Unser brothers, when his DayGlo-red colored racecar spun across the track in Turn 4 and slammed into an inside retaining wall.

The DayGlo car exploded in a ball of flames. It was a terrible, devastating crash.

Swede Savage survived the impact but he would die in the hospital 33 days later. He was only 26 and a rising star when the racing gods intervened. He was the last driver to lose his life at Indianapolis as the result of a crash during the race.

Angela Savage of Boulder City was born a few months after her father died.

She grew up without her a father; it wasn’t easy. She had issues, she said. Then her older sister, Shelly, died of leukemia. How much tragedy can one soul bear?

Angela Savage kept some of her dad’s racing things in a storage shed. Rarely, if ever, did she take them out. To racing fans, Swede Savage was a hero. To Angela Savage, he was just the father she never knew.

Then, an epiphany. Race fans reached out to her via social media. The people at Indianapolis Motor Speedway reached out to her, too. They flew Angela and her family in for the 2014 race. The next day, they even allowed her onto the track, in Turn 4, for a moment of reflection.

“Going to the track in 2014 changed my life,” she said before departing for this year’s 500, which will be her third — one more than her father drove in. “It was like somebody plugged a lamp into a wall.”

When she returned from Indianapolis, Angela Savage started a Facebook page to honor the father she got to know through other racing people. She got to know Rich MacDonald and Eddie Sachs III, siblings of two other drivers killed in a fiery wreck at Indianapolis; she now has a talk show streaming on the Internet — “Good News with Angela Savage.” Most of her guests are racing people. A lot knew her dad.

One of her recent guests was Pippa Mann, who will be the only woman driving in Sunday’s race.

Pippa Mann told Angela Savage she’s going to take her dad and sister along for the ride on Sunday. She said she would inscribe their names in the cockpit for the 100th running of the Indianapolis 500.

Las Vegas Review-Journal sports columnist Ron Kantowski can be reached at rkantowski@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0352. Follow him on Twitter: @ronkantowski