Raiders’ Kolton Miller reaches NFL dream to help brother

ROSEVILLE, Calif. — Hospital nurses said Kolton Miller would have topped 10 pounds at birth in Redwood City, California, if not for the C-section weeks before the due date.

At 6 months, he was baptized in a white embroidered outfit. Its size was intended for a 24-month-old toddler. Two weeks before the ceremony, it fit comfortably. By the day of, buttons barely fastened.

From 10 to 16 years old, his shoe size matched his age. His mother Karrie Miller fought his growing pains with massages, drawn baths and German chocolate cake. He and father Dan Miller often wrestled until, once as a teen, Kolton threw Dad darn-near across the width of a room.

“You’re not fun anymore,” Dan said to him.

Kolton Miller became the tallest active Raiders player at 6 feet, 8 5/8 inches when the former UCLA offensive tackle was drafted April 26 with the No. 15 overall pick. But growth spurts aren’t what led him here. Not entirely. He cites his brother as his main motivation.

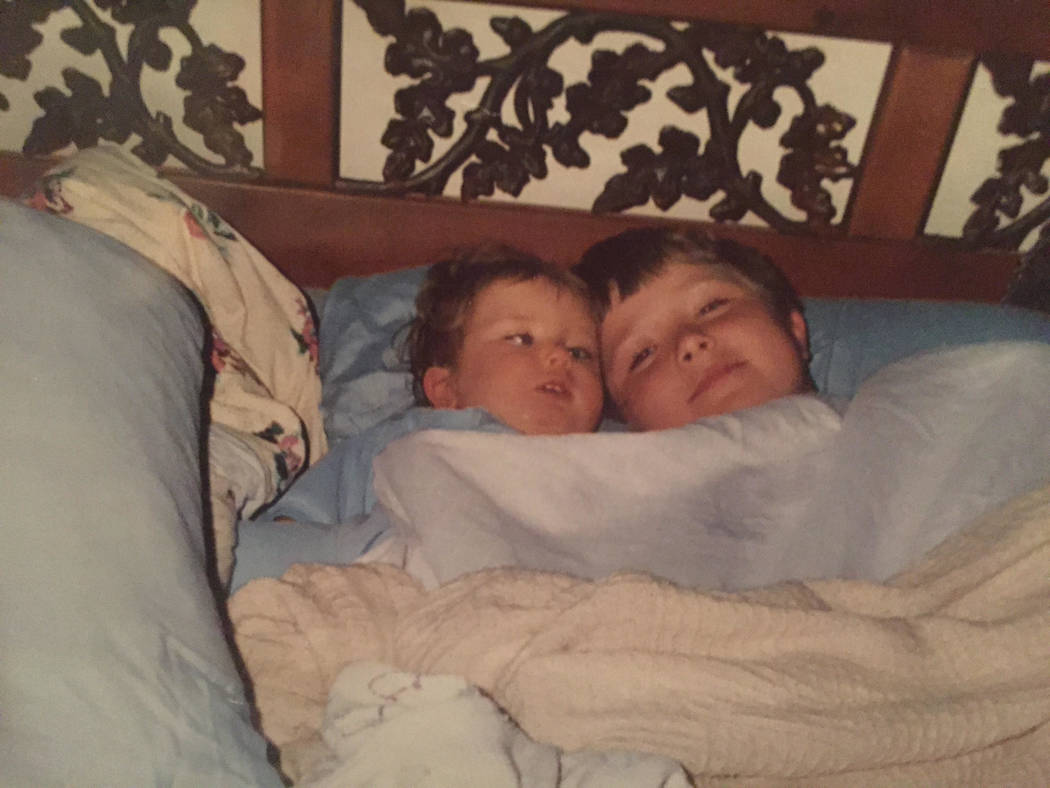

As a boy, Kolton asked his parents for a sibling. They tried for years in vain. Finally, he was 6 when Chad was born at 2 pounds, 13 ounces. They met behind the glass of a neonatal intensive care unit and formed a strong bond.

Their relationship and the NFL career it inspired now allow Kolton to provide financial security to Chad.

“I’m his number one fan,” said Chad, who wore a Raiders hat to school the past two weeks. “And he’s mine, too.”

“I want him to be taken care of,” Kolton said.

A protector

Karrie Miller cannot help it.

She sees some of her own father in Kolton.

Her dad, Glenn Blomseth, was a professional protector. He wore an FBI ring commemorating his graduation from the agency’s academy. The 6-foot-4 man, whose Scandinavian bloodlines lent height to Kolton, served as a police lieutenant in Antioch, California, before retiring as the department’s interim captain.

On March 26, 2002, he was on call for his family.

A doctor prescribed Karrie bedrest at home in Alamo, California. Complications arose from a pregnancy still in its 26th week. Blomseth stayed overnight. Early in the morning, when complications worsened, he urged her and Dan not to wait for an ambulance, Karrie said.

He’d watch Kolton. Just go. Hurry. Go.

Specifics regarding the situation are a private family matter, aside to say Blomseth’s crisis management proved momentous. Karrie and Chad endured, the latter born minutes upon arrival at a Walnut Creek hospital. Once Chad was home, a proper introduction with Kolton could be made.

It became clear Kolton was a protector, too.

If Chad sat atop someone’s lap on a couch, Kolton sat next to them. If Chad was in a baby carrier, Kolton often sat on the floor, playing beside him. Chad was unable to sit up on his own until 2 years old. When needing someone against whom to prop himself, big brother was there.

Chad was born with Moebius syndrome, a rare neurological condition affecting certain cranial nerves linked to muscles that control eye movement and facial expressions. Physical therapy and other medical care often required attention. This meant Dan and Karrie missed some items on Kolton’s extra-curricular calendar, including certain sporting events.

No problem.

“We had people who would take him to his practices and things like that,” Karrie said. “We would address things with him. He’d be like, ‘No, I’m fine. Take care of Chad.’ That was his response. ‘Take care of Chad.’”

Kolton’s maturity extended beyond height.

Before his parents’ divorce, Dan and Karrie regularly hosted family functions. Kolton often socialized with adults, not kids, at the parties. His youthful spirit would surface when retiring to his bedroom room for a wardrobe change. He returned in a Superman or Batman costume.

In elementary school, his morality was the stuff of superheroes, as teachers marveled over his willingness to confront bullies. On multiple occasions, Kolton witnessed a peer being mistreated. The tall boy from Redwood City did not spectate. Rather, he spoke up and stepped in.

Such acts included helping female students whose clothes were being pulled or had a ball stolen during a game of Four Square.

“It was how I was raised,” Kolton, 22, said. “I was raised to be a good kid. Maybe it came naturally because I was bigger than other kids.”

Protecting quarterbacks came naturally, too.

Shared success

Kolton kept an open mind with sports.

He first tried youth soccer but, after a few practices, told his parents he did not enjoy it. They asked if he wanted to quit. His response: “I’m not a quitter.”

He lasted the full season before retiring his shin guards for good. He later played basketball, a more natural fit because of his height, and baseball. He dabbled in track and field in high school, hurling in the discus and shot put.

But no sport compared to football.

Kolton was a two-way player at Roseville High, an offensive tackle and defensive lineman. One of his teammates at the time, running back Matt Razzano, is the son of Dave Razzano, the Raiders’ director of football research.

Chad was a four-year captain to Kolton’s cheering section, watching games and practices from the stands or sideline. Kolton often invited him into the postgame locker room where Chad effused positivity, individually congratulating teammates on a good game with high fives or encouraging them after a loss.

Coaches at Roseville saw Kolton’s potential. Jon Osterhout soon did, too.

Dan Miller reached out to Osterhout, coach at Sacramento’s American River College and founder of offseason training program Linemen Win Games, during Kolton’s sophomore year. Other alumni from the academy include Raiders defensive tackle Eddie Vanderdoes, who also attended UCLA.

“He had all the redeeming qualities that you look for in a guy who’s truly trying to create the best version of himself,” Osterhaut said. “Extremely inquisitive. Very professional in everything, from being there early to staying there late, asking great questions and really trying to improve himself every single day.”

Attention from colleges followed.

When Kolton attended an Oregon football camp, he brought Chad with him. When he made official stops to Wisconsin, Oregon State and UCLA, he brought Chad with him. Over his life, Kolton outgrew shoes and shirts and pants. His profile widened and expanded across the country.

He always brought Chad along.

Chad, 16, now attends Roseville High. Before the draft, he regularly would be asked about his brother. Chad would discuss his strong performance at the NFL Scouting Combine — Kolton’s broad jump of 10 feet, 1 inch set an event record for an offensive lineman — or which teams Kolton was visiting.

“You could just see the shine in his face that he was so happy,” said Adam Lenakakis, Roseville offensive line coach. “Now that he is a Raider, it’s even better because he’s only an hour and a half from his brother. He’ll be able to watch him in training camp and the preseason and as many home games as they can get to, of course.”

The missed game

A graham-cracker square is covered in a cookie dough mixed with marshmallows and chocolate chips. Once baked, the crunchy, gooey result from Cookie Connection, a Roseville-based gourmet cookie company, is the highlight to a care package Karrie routinely presented Kolton and his fellow UCLA offensive linemen when driving to all home games.

That was until Oct. 1, 2016, against Arizona. No cookies. No Mom and Chad.

Kolton was entering his fifth start at right tackle as a redshirt sophomore. As game day approached, Karrie called Kolton and informed him she’d be unable to travel to Rose Bowl Stadium in Pasadena, California. She and Chad would watch from home in Roseville instead.

On the morning of the game, something felt wrong.

“She mentioned, ‘I have this awkward, strange feeling something is going to happen,’” Chad said.

Karrie repeated the sentiment, as Chad tried to assure their mother. But in the second quarter, a teammate accidentally was tackled into Kolton’s lower left leg. Kolton heard four pops is his knee. Never before needing surgery, he feared the worst. Fortunately, it was a spiral ankle fracture that did not require a procedure, although he missed the remainder of the season.

Missing the next game irked Kolton most. He could not help Josh Rosen, who suffered a season-ending injury on a fourth-quarter hit.

Kolton was unable to protect him.

“You watch, and you feel like it’s partly your fault,” Kolton said. “Of course, you can’t say that, but it kind of feels like that.”

Still growing

While at UCLA, Kolton had a sense he was NFL-bound. He told his parents they didn’t need to worry. He would take care of Chad. With an upcoming four-year contract worth more than $13 million, he is positioned to do so.

But Kolton has other goals.

He wants to earn a starting job in 2018, he said. He wants to win a Super Bowl. One day, he wants to wear a gold jacket as a Pro Football Hall of Fame inductee. These are goals he can chase now, potential future moments he can share with his family.

Last year, Chad was among those to visit Kolton for Thanksgiving and a Nov. 24 game versus California. Karrie was preparing for the day when, from a hotel restroom, she overheard her two sons chatting. Kolton waved over Chad and told him he’d be going to the NFL soon. He asked what his thoughts about it were.

“Chad said, ‘That’s pretty cool,’” Karrie said. “And he said to Chad, ‘If you don’t want me to go, I won’t go.’ And Chad was quiet, and he said, ‘Did you hear me? If you don’t want me to go, I won’t go because I’m going to do this for you.’

“And Chad said, ‘No, bro. I want you to go.’ And he said, ‘OK, I’m going to do it for you, Chad.’”

More Raiders: Follow all of our Raiders coverage online at reviewjournal.com/Raiders and @NFLinVegas on Twitter.

Contact reporter Michael Gehlken at mgehlken@reviewjournal.com. Follow @GehlkenNFL on Twitter.