Norris driven to win latest fight

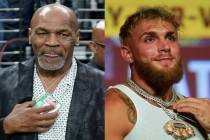

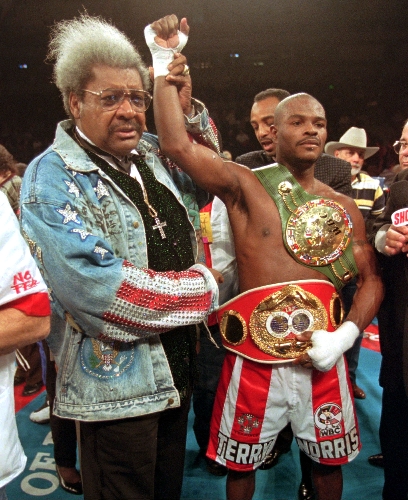

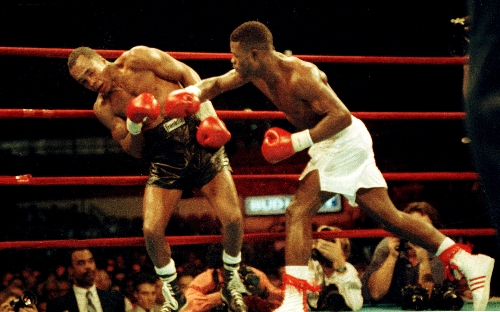

Terry Norris counts his victories over Sugar Ray Leonard and John “The Beast” Mugabi as the most memorable moments of his Hall of Fame boxing career.

But the former four-time light middleweight world champion can’t remember those fights or any others – nor, for that matter, the date of his 2009 wedding to his wife, Tanya.

Due to repeated blows to his head, Norris, 45, suffers from Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy – previously known as pugilistic dementia, or punch-drunk syndrome. It’s a degenerative brain disease with symptoms that include memory loss, confusion, depression and emotional outbursts.

Norris also is afflicted with Parkinsonism, a group of nervous disorders similar to Parkinson’s disease and marked by muscular rigidity, tremors, speech and swallowing problems, balance and walking problems, and more.

During a recent interview at Bellagio, Norris appeared physically fit but struggled at times to express his thoughts. He also broke down crying more than once.

“I need something to correct my memory. I’m losing ,” Norris said, before he suddenly stopped talking, buried his head in his hands and began crying and grunting in frustration.

Said Tanya: “The problem with Parkinsonisms is you can’t articulate. Sometimes he wants to say something and he just can’t.”

Regaining his composure after wiping away tears, Norris said, “I’m crying because it’s embarrassing. It’s embarrassing.”

DENIAL OF THE DAMAGE

Norris is the most high-profile athlete involved with the Professional Fighters Brain Health Study and Retired Pro Athletes Clinic at the Cleveland Clinic Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health in Las Vegas.

He started showing signs of CTE late in a career that included 295 amateur bouts (291-4), 56 professional fights (47-9, 31 knockouts) and thousands of rounds sparring.

Before his request for a boxing license was denied in 2000 by the Nevada Athletic Commission because of impaired speech indicative of brain damage, Norris was in denial about his condition.

“My dad and people in my camp were (asking) me, ‘Why (are you) stumbling?’ Even when I danced,” Norris said. “I used to be real smooth in the ring. My dad was always saying, ‘What’s wrong with you? You’re not fighting like you used to fight.’

“I wanted to convince myself I felt like the old Terry, but I didn’t.”

Dr. Margaret Goodman, a Las Vegas neurologist and former chief ringside physician for the NAC, vividly recalls the night in 1999 when she ran into Norris at the MGM Grand Garden, shortly before his brother, Orlin, fought Mike Tyson.

Goodman realized, to her horror, that something was seriously wrong with him.

“I said hello to him, and he couldn’t enunciate the words,” she said. “I remember pretty much running out to the ring where Dr. (Flip) Homansky is and I said, ‘Terry can’t talk.’ ”

The following year, Goodman and Homansky were part of the NAC when it denied Norris’ request for a license.

At the meeting, a tape of a 1994 TV interview of Norris was played, and Goodman said he “sounded clear as a bell.” It was a stark contrast to the slurred speech Norris used while answering questions from the NAC, which denied his request by a 5-0 vote.

“I’m not exaggerating. Every one of the commissioners had a tear in his eye, because it was right there staring you in the face what had transpired to this amazing young man,” Goodman said. “You didn’t need a million-dollar study to tell you this young man didn’t belong in a boxing ring anymore.

“Everybody respected Terry so much. To see that happen to such a wonderful boxer and wonderful person was tragic.”

GETTING HELP

Norris, a father of six who got divorced after he retired, continued to deteriorate in the years that followed. He self-medicated with alcohol, ballooned to 215 pounds and all but lost his ability to speak.

“My (14-year-old) daughter helped me talk,” he said. “She would speak for me because (people) couldn’t understand me.”

It wasn’t until 2009 that Norris – thanks to Tanya, a personal trainer and former medical school student – finally was diagnosed and treated, first at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, where the couple resides, and more recently at the Lou Ruvo Center.

“I’ve been to a number of doctors. I’m tired of going to doctors,” said Norris, who works out daily, has slimmed down to 170 pounds and attends appointments for speech therapy, physical therapy, balance therapy and psychological therapy.

“It’s working, though,” he said. “I feel a lot better. My speech is a lot better.”

Norris, along with Tanya, is an advocate for fighters’ safety and helps boxers through his foundation “The Final Fight.”

“His quality of life has completely changed,” Tanya said.

RESEARCH LEADER

The Lou Ruvo Center for Brain Health is at the forefront of CTE research. In addition to the fighter’s study and retired athletes clinic, the center recently hosted a national CTE conference that it hopes will become an annual event.

“The perception is, ‘How can any useful science come out of Las Vegas?’ In some sense, here’s an example of where we are among the leaders in the field,” said Dr. Charles Bernick, associate medical director of the Lou Ruvo Center. “We’re the ones who put on the (CTE) conference. This is the newest neurodegenerative disease, and we’re on top of it.”

The fighters study, which started in 2011 and features more than 270 boxers and mixed martial artists, runs participants through a battery of annual tests and measures changes.

The retired athletes clinic opened this year and has treated about 15 participants, even offering free comprehensive testing and treatment to those who can’t afford it.

“We should have some resource that actually helps these people instead of just poking and probing them,” Bernick said.

CTE has been known to affect boxers since the 1920s, but the disease has received more attention recently because of confirmed cases of CTE in retired pro football players and other athletes who’ve had a history of repetitive brain trauma.

“The bottom line is it may not even take that much trauma to the head to develop the condition,” said Goodman, who attended the CTE conference. “No one really knows. This is the problem. There’s really no test to determine when a fighter is starting to show evidence of (CTE). By the time they have the problem, it’s too late.

“How do we test this before it gets to the point of no return? Hopefully with the Lou Ruvo Center doing the research they’re doing, they can come up with a way to make a determination before this all happens.”

BREAKING POINT

While Bernick said it’ll probably be years before neurologists can determine when an athlete has reached the point in his career when additional blows are likely to cause permanent, irreversible brain damage, he hopes to discover that information through the pro fighters study.

“As far as we know, we are the only study that’s actually following people early in the disease process, or when they’re exposed,” he said. “We’re really interested in the start of the disease.”

The NAC, which requires boxers to have only one MRI at the start of their career, and the Ultimate Fighting Championship are supportive of the study. Bernick added the Lou Ruvo Center has applied for some of the $30 million NFL owners donated to the National Institutes of Health for brain injury research.

“Anything that’s involving potential funding for understanding CTE and head trauma, we’d be interested,” Bernick said. “We are probably better positioned than most places.”

In addition to the aforementioned research, the Lou Ruvo Center has developed an iPad-based test that can assess brain function and can be used at ringside. It also has a device under development that can be integrated into a mouthguard to measure the force of impact to the head.

Terry and Tanya Norris hope to come out with a book and a workout DVD, and also want to star in a reality show that might be called “Lady and The Champ.” Terry plans to continue to take part in the study and clinic at the Lou Ruvo Center.

“I think they’re doing a great job there,” Terry Norris said. “Dr. Bernick, he’s cool, and all his staff, they treated me well.

“I think he will be the one to get the job done. I hope he finds the cure.”

Contact reporter Todd Dewey at tdewey@reviewjournal.com or 702-383-0354.