51s recount what it’s like to be a first-round draft pick

Being a first-round draft pick comes with life-changing money.

But it also comes with a unique set of pressures — be it internal or external — and expectations that accompany the opportunity of a lifetime.

With the Major League Baseball First-Year Player Draft starting Thursday, four 51s and manager Wally Backman took a trip down memory lane, recounting their experiences as first-round selections.

And while they mostly said they were treated similarly to other draft picks, first-rounders undoubtedly have a different experience moving through organizations.

“If you’re a first-round pick or a second-round pick or even a third-round pick … teams are going to give you more of an opportunity because they have that investment,” said Las Vegas starter Sean Gilmartin, a first-round pick in 2011. “I think there is some leeway for a first-round pick, top-round picks. You’ve just got to go out there and not worry about that and just do your thing.”

Josh Smoker

The spring of 2007 saw an influx of visitors in Calhoun, Georgia, a small town about 70 miles northwest of Atlanta.

The visitors — about 40 to 50 scouts — were there to see Calhoun High School’s top players.

“I think it was amplified a little bit just because we had a few prospects on the team,” said Smoker, a left-handed pitcher.

But Smoker was the first of his teammates picked, selected in the supplemental first round — 31st overall — by the Washington Nationals.

As a first-round pick, he said he was treated fairly and more or less the same as everybody else.

“Playing-opportunitywise, you’re always going to get to play over some of the other guys, but at the same time, you have to perform,” Smoker said. “If you don’t perform, that first-round status slowly starts to fade away a little bit. They give you a lot of money to perform, and they expect a lot out of you.”

Smoker didn’t have much of a chance to show the Nationals what he could do, constantly hampered by injuries while with the organization. As he battled through them, he put an increasing amount of pressure on himself to stay healthy.

That didn’t work, and he found himself in independent ball, though he had a tough time latching on with a team there, too, because of his injury history.

Eventually, his first-round status came in handy as he found his way back to affiliated ball, with Smoker saying it would have been a lot harder latching on with a major league organization if he had been a later-round guy.

“I think just getting a change of scenery was a good thing,” said Smoker, 27. “I’m grateful to the Nationals and everything they offered me and every opportunity they gave me, but like I said, a change of scenery is defintiely a good thing, too.”

Sean Gilmartin

When Sean Gilmartin was drafted in the 31st round out of high school as an outfielder, he considered signing with the San Diego Padres.

“I thought I was ready at the time to start my professional career,” Gilmartin said. “Key word, I thought I was ready.”

He decided he wasn’t, and opted for his other choice — a scholarship to Florida State.

He was going to be a two-way player, playing in the outfield and pitching, but because of need, he became the school’s Friday night starter the third week of his freshman season and held that role throughout the rest of his college career.

After his junior year in 2011, he was drafted again, this time in the first round (28th overall) by the Atlanta Braves.

The Braves gave no indication they were taking him — a scout called the day before, but Gilmartin described that conversation as a normal check-in.

Shortly before he was picked, the Cincinnati Reds called. They had the pick before the Braves and wanted to work out a deal in which Gilmartin would sign for below slot money.

Gilmartin thought he would be drafted anywhere from the first to third round. If he turned down the Reds’ offer and then wasn’t picked until the third round, he would have missed out on a significant amount of money.

“I’m a 21-year-old kid thinking, ‘Wow, I’m going to sit here and I’m about to pass up that much money. What am I doing?’” Gilmartin said.

He quickly hung up and called his parents and agent, who all told him it was a decision he would have to make for himself.

He decided to give the Reds a call back. They had already gone with another pick.

“Me having that little bit of hesitation there, it was kind of a blessing in disguise, because no more than 30 seconds later, I’m getting a phone call from the Braves telling me that they’re taking me,” said Gilmartin, a 26-year-old left-hander.

Brandon Nimmo

Brandon Nimmo’s path to becoming a first-rounder was about as atypical as they come.

With no high school baseball in Wyoming, Nimmo played American Legion — not the ideal place for attracting scouts.

But after his coach took him to the Tournament of Stars in 2010, scouts started noticing him.

“Everybody was like, ‘Who is this kid?’ And so then they would come out to watch,” Nimmo said. “It really started there.”

Nimmo wound up being the New York Mets’ 2011 first-round pick, going 13th overall, the first spot he said he could possibly go.

“We had a good inclination that I probably wasn’t going to fall past 33, but we didn’t know,” Nimmo said. “There’s a lot of uncertainty in the draft because we also knew that (I) couldn’t get picked, too, and I would have just gone to (the University of) Arkansas.”

Nimmo played it safe — even though he was invited to attend the draft in person, an honor extended only to players who are essentially locks to become first-round picks, he wanted to avoid the Brady Quinn “horror story.”

Quinn, a quarterback out of Notre Dame, was projected to be a top pick in the 2007 NFL Draft. He showed up to the draft only to see himself fall to the 22nd pick.

Things worked out better for Nimmo.

He watched the draft at home with his family and best friend, finding out the Mets picked him when he saw his name flash across the TV. He received a call shortly after.

“It’s part of a dream come true,” said Nimmo, a 23-year-old outfielder. “It’s the start of a new chapter in your life and just a very, very fun day that I’ll never forget.”

Gavin Cecchini

Unlike Nimmo, Gavin Cecchini wasn’t afraid of the Brady Quinn horror story.

By the beginning of his senior year, the shortstop knew he would be a first-round pick, and, sure enough, the Mets picked him 12th overall in 2012.

“We were getting feedback from the scouts, from my agent and stuff like that, there was no way I was going to be slipping,” Cecchini said. “I either had to get seriously injured or something like that, but I was projected to go first round the whole year.”

If Cecchini had slipped to the second round, he said he would have gone to Mississippi instead of signing.

But the possibility of that happening was slim, because if the Mets hadn’t selected him, he said teams such as the Toronto Blue Jays (picks 17 and 22) and St. Louis Cardinals (19) had been especially interested.

Shortly before he was picked, Cecchini had a predraft workout at Citi Field. He took in Johan Santana’s no-hitter from a suite and met some of the players. A few days later, he attended the draft with his family at the MLB Network studios in Secaucus, New Jersey, where he met CC Sabathia, Torii Hunter and Mike Cameron.

After the draft, he went back to Citi Field with Kevin Plawecki, whom the Mets picked in the supplemental first round that year, and they got to take batting practice on the field.

“People can predict the draft, and they can make mock drafts all they want … but you don’t really know because so many things can happen,” said Cecchini, 22. “I did not know that I was going to be picked by the Mets until two minutes before they picked me.”

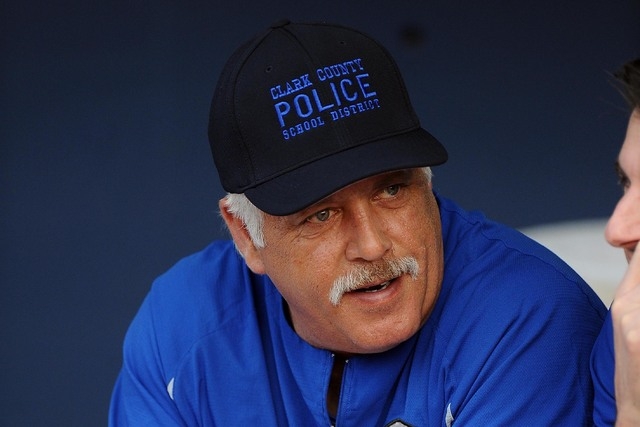

Wally Backman

Wally Backman was sitting in school — typing class, if memory serves — when he found out he was drafted over the loudspeaker.

The 51s manager was selected 16th overall by the Mets in 1977.

From what he had heard, he knew he would go in the first two rounds. The Mets had watched him play “quite a few times,” though the only team to bring him in to showcase for them was the Seattle Mariners, who picked 26th.

In the span of a few weeks, he signed, went to Florida for workouts and then began his professional career in the New York-Penn League.

Backman’s signing bonus was $70,000, a far cry from the $2,660,800 assigned value connected to the 16th overall pick this year.

He used it to buy a truck, and eventually it was the money that got him through the minor leagues, as he made $500 a year in the New York-Penn League.

He moved through the minor league system relatively quickly, debuting in the majors in 1980 when he was 20.

Now as a manager, Backman, 56, said first-round picks aren’t really treated differently, though there are a couple of little things that might come up.

Nimmo and Cecchini, for example, are staples in the lineup — Backman wants to make sure they get 500 plate appearances — and he doesn’t pinch-hit for them, letting them have their chances against tough pitchers.

“The opportunity for a high round draft pick … they’re going to get an opportunity, especially the way that money is today,” said Backman, a second baseman who played 14 years in the majors, “but I would say there’s no coddling those guys compared to somebody else.”

Contact reporter Betsy Helfand at bhelfand@reviewjournal.com. Follow on Twitter: @BetsyHelfand