A billion gallons is a lot of water. Enough water that it would require nearly 30,000 tanker cars—a train stretching from Summerlin to San Diego—to deliver. Every day, Las Vegas Valley Water District (LVVWD) customers shower, brush their teeth, fill sports bottles, make coffee, and irrigate their landscapes, unaware of a vast network of largely invisible water infrastructure that brings highly treated water from Lake Mead to faucets around the valley.

Having a reliable water supply available at every tap and fire hydrant requires a tremendous amount of infrastructure. The LVVWD’s enormous pumping stations that can move 1.25 million gallons of water a minute and 6,500-mile labyrinth of water mains and service lines are only part of the equation. One of the most important components of Las Vegas’ elaborate water system is the network of reservoirs, a collection of nearly 80 concrete and metal behemoths that collectively stores nearly a billion gallons of drinking water.

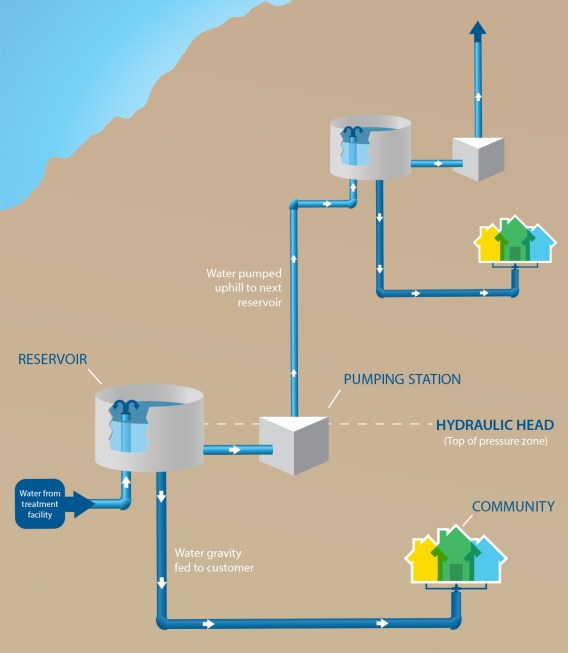

Discreetly tucked behind stucco walls in neighborhoods throughout the LVVWD’s 300-plus-square-mile service area, these reservoirs do more than just hold water—they help deliver it. With nearly 2,000 feet of elevation difference between the valley floor and the community’s western edge, gravity can be an ally or an adversary. LVVWD engineers have harnessed its power to increase reliability and reduce power costs. The siting of the community’s drinking water reservoirs is anything but random; choosing locations involves anticipating how many customers it will need to supply and, perhaps more importantly, the elevation of the homes and businesses being served. The LVVWD strategically positions reservoirs upgradient from customers, allowing gravity to push the water through the water lines and build pressure.

Capitalizing upon the valley’s topography has two advantages. The first is decoupling water delivery from the community’s electrical grid; because almost all customers are “gravity-fed”, a power outage won’t cause an immediate water service interruption. The second is reduced energy costs, which directly benefit customers. LVVWD operations technicians fill the reservoirs during “off-peak” hours, when electrical costs are at their lowest, so that its energy use is minimal during the high-use morning and early evening hours. Given that treating and delivering water is the single greatest use of electricity in Southern Nevada, this small operational adjustment yields huge dividends.

Like all facilities, reservoirs have a finite service life. During the next decade, the not-for-profit LVVWD will invest $600 million replacing and/or renewing water system components—including many of the community’s water reservoirs—to keep water service reliable, expanding the water distribution system, and protecting water quality. For more information about the LVVWD’s infrastructure reinvestment initiative, visit www.lvvwd.com