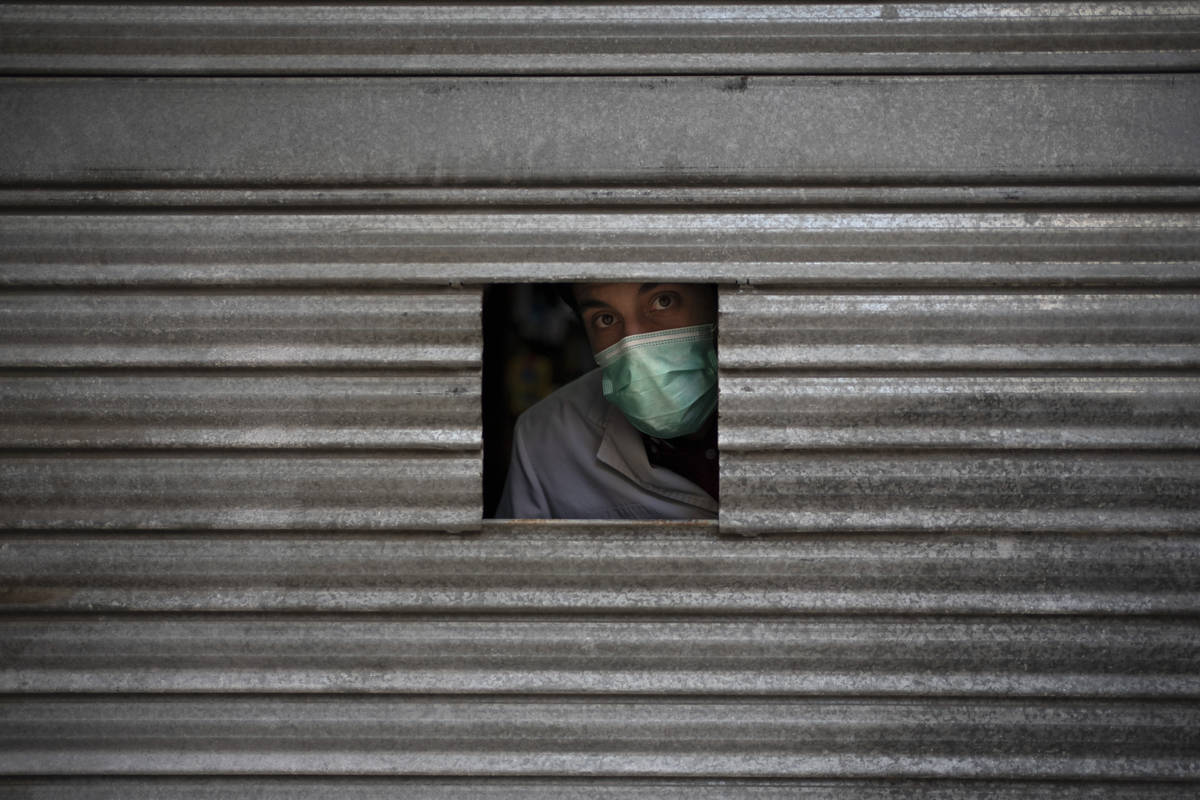

EDITORIAL: Virus lockdowns don’t appear to have worked as advertised

As states begin to relax their pandemic restrictions in the wake of dramatic reductions in confirmed cases, hospitalizations and deaths, some observers are reaching a sobering conclusion: strict government lockdowns didn’t do much good.

“Lockdowns can destroy the economy,” wrote Phillipe Lemoine of the Center for the Study of Partisanship and Ideology in a Wall Street Journal oped last week, “but it’s starting to look as if they have minimal effect on the spread of COVID-19.”

Mr. Lemoine, who says he favored the tactic early in the pandemic, notes that “not a single government has published a cost-benefit analysis to justify lockdown policies.”

The Associated Press picked up on the theme over the weekend, finding that states which enacted tight restrictions on commerce and other activities performed no better in preventing coronavirus deaths or confirmed infections. California Gov. Gavin Newsom, for instance, imposed some of the most draconian curbs in the nation. Florida was at the opposite extreme. Yet “California and Florida have experienced almost identical outcomes in COVID-19 case rates,” the AP reports, and both rank in the middle in terms of deaths per capita.

The latter is even more significant given that California’s younger demographic means that a higher percentage of Florida residents were at high risk for serious virus complications.

The AP also highlights the contrast between South Dakota and Connecticut, which are both among the 10 worst states in terms of death rates. But the latter was much more aggressive in restricting the actions of its residents, while the former took a laissez-faire approach.

While there are obviously many factors in play when making comparisons between the states, such anecdotal evidence is in line with a peer-reviewed Stanford study of eight countries — including the United States — published in January that found “no clear significant beneficial effect” from stay-at-home orders and business closures.

Amesh Adalja, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told the AP, “This is going to be an important question that we have to ask ourselves: What public health measures actually were the most impactful and which ones had negligible effect or backfired by driving behavior underground?”

Indeed. Even comparing raw numbers on deaths and case counts fails to take into account the staggering economic, academic and mental health costs associated with lockdowns and school closures.

In coming years, we’ll learn more about the various public health strategies governments and public health officials employed to fight COVID and their long-term ramifications. But at this point, the long-term lockdown experiment appears to have been an expensive failure.