COMMENTARY: Risk, the herd mentality and public schools

Last month, I offered some bad news for megacity office workers: You’re probably not going back anytime soon. Today, I have to break it to the parents among them that I suspect your kid isn’t going back to school this year, either. Some of you — including those in Las Vegas — already knew that, because your district has announced it will be 100 percent online.

Yes, I know that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has revised its older, more conservative guidelines to urge schools to reopen, saying it will be “safe in communities with low SARS-CoV-2 transmission rates.” But that’s a description many states don’t currently fit. No matter what the CDC says, moreover, districts moving to in-person classes will face daunting logistical challenges, fierce resistance from teachers and even pushback from parents. Those challenges will be exacerbated by a phenomenon I first noticed as a tech consultant in the 1990s.

Back then, we had a saying: “No one ever got fired for buying IBM” (sometimes “Microsoft”). Those companies might not have been making the best products, and they were definitely more expensive than the competition. However, while their products might have been a bad deal for the users, they delivered excellent paycheck insurance for IT managers: If something went wrong, you could always say, “I used the industry standard.” That defense wasn’t available to anyone who tried to “think different.”

Once a few folks decided upon a “safest option,” everyone else ended up falling in line behind them. And this sort of behavior is hardly limited to computer nerds — money managers, for example, are notorious for herding.

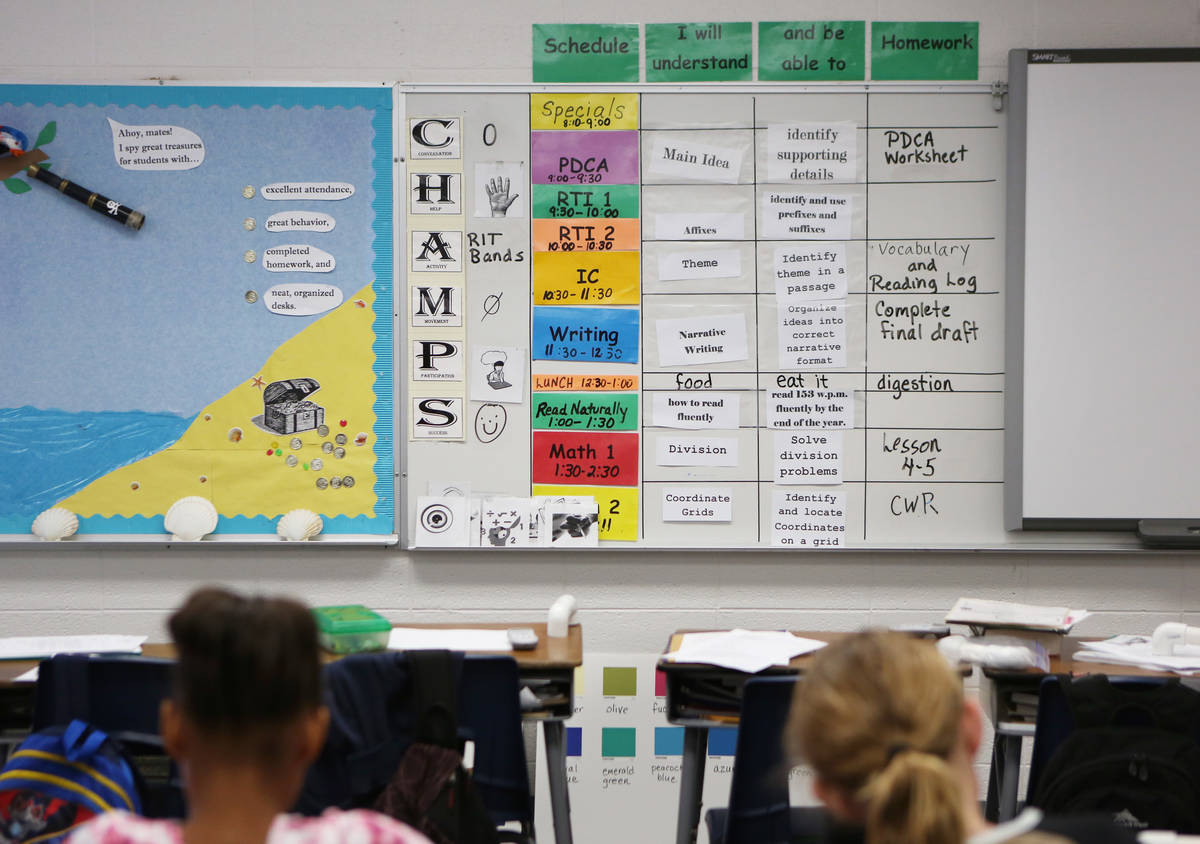

So are schools likely to be. While the decision to reopen them may look to us like a complicated trade-off between the epidemiological risks of reopening and the socioeconomic costs of staying closed, for the people making those decisions, the stakes are even more perplexing. Teachers wonder, “How can I possibly avoid catching COVID-19 in a classroom full of natural anarchists whose personal hygiene skills are still evolving?” Administrators puzzle over a related query: “What happens if a child dies?”

Spoiler alert: The parents may well sue, and the district officials who made the call will, at minimum, spend days in court defending the placement of every single hand-sanitizer dispenser. Long before then, frightened teachers will be pointing to the all-online districts and demanding to know why their district doesn’t care about the safety of its teachers or kids. If almost every school opens up, those officials could take refuge in an “industry standard.” But as some districts close, the pressure on others begins to grow; as more give into it, I expect the snowball will become unstoppable.

Parents are familiar with this behavior, by the way. It’s the same phenomenon that has been ratcheting up the demands on them for years.

When I was a kid, most 11-year-olds were allowed to sit alone in a car while Dad ran into a store, bike miles to a friend’s house, wait at the bus stop by themselves or stay home alone for a few hours after school until mom got home from work. Today, most parents would never dream of allowing their children to do any of these things, even though crimes against children have been falling for decades.

Talking to those parents, I often find that they are buying themselves a kind of regret insurance. If they do everything the other parents do, and something happens to their child, they will still feel unimaginably awful. But they won’t have the added pain of feeling it happened because they were irresponsible.

To give themselves a margin of error, parents tend to take cues as to what’s “responsible” from parents who are slightly more anxious than they are. Because those parents are doing the same thing, this means standards are increasingly set by the most neurotically overprotective mothers and fathers around.

Even “free-range parents” who resist that psychological pressure often find themselves forced to comply when government authorities adopt the narrowing standards. Authorities, too, are being driven by loss-averse logic: The results of missing one case of neglect or abuse loom much larger than the consequences for parents who are forced to hover like helicopters, or for children who end up caged like a canary.

That’s the environment in which we’re asking districts to reopen schools. In deference to President Donald Trump, those in the reddest states may resist the pressure toward safety at all costs. But in blue states, near megacities, the effect is more likely to go the other way: The more Trump insists, the more parents will resist.

Of course, policy should not be set by doing whatever Trump recommends or its opposite. Nor should policymakers blindly pursue safety over every other public good. But if we wanted a different process, some careful weighing of costs against benefits, then that’s a conversation we probably should have had several decades back.

Follow Megan McArdle on Twitter, @asymmetricinfo.