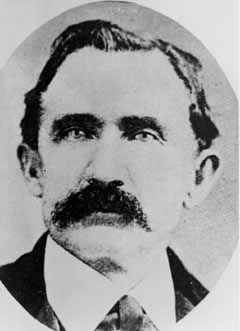

William Bringhurst

By 1855, travelers already knew the harshness of the Mojave Desert. They knew that the 52-mile jornada from the Muddy River to Las Vegas was best attempted in winter. Yet on June 13, perhaps 15 young men broke camp, filled every keg, bucket and fruit jar with water, cracked their bullwhips and headed southwest on a day one called the hottest he had ever seen. Men and oxen plodded all night, following a trail marked by bones.

It was 3 p.m. on the 14th before they reached the good water and grass of Las Vegas. “Their teams and their wagons were pretty well used up,” remarked their historian. Even so, some men dumped their other cargo, refilled water barrels, and headed back into the desert to help another party of 15 who were driving weaker teams and started the hard journey 24 hours later. It was June 15 before the last stragglers made it into camp.

What drove men into the desert summer was not a matter of life and death, but of eternal life. Once assigned to teach their Mormon faith to the Indians of the Las Vegas Valley, they did not wait on a better season, but left almost at once.

None would strive harder to complete the mission than its president, William A. Bringhurst. So committed he became that, when the mission’s purpose was changed, he defied even the will of his church’s leader, Brigham Young.

Born in Philadelphia in 1818, Bringhurst married Ann Dillworth in 1845, and traveled to Utah with the John Taylor Company, arriving in 1847. But for nearly two years, beginning in 1855, the diaries of others paint his efforts to colonize, civilize and proselytize Las Vegas and its native inhabitants.

Las Vegas was targeted for several reasons. The main road through Las Vegas, mislabeled as the “Old Spanish Trail” when John C. Fremont mapped it in 1844, became so important to Utah colonists that it was also called the “Mormon Road.”

Up that road came cuttings of California fruit trees, destined to bloom in Utah. Mormon converts from abroad landed at Pacific ports and traveled up the road to Utah. As early as 1851 church authorities envisioned a line of settlements, between the ports of the Pacific and Utah’s southern counties, to provide travelers with food, fodder, and blacksmith services.

The way stations also were to protect travelers and the mails from hostile Indians, and there may have been some hope of finding and exploiting minerals.

Some historians have denied any relation between the Las Vegas Mission and the Mormons’ fear of military confrontation with the United States. Yet an alliance with desert Indians was clearly on the mind of colonist John Steele, when he wrote: “We can have 1,000 brave warriors on hand in a short time to help quell the eruption that might take place.” Brigham Young himself, in a meeting with departing missionaries that spring, said of the Indians “… by and by they will be the Lord’s battle ax in good earnest.” Ultimately, the differences were settled without war.

The missionaries were supposed to teach the Las Vegas Paiutes, who were hunters and gatherers, how to farm.

But in the eyes of many, notably Bringhurst, the main purpose was religious. Mormons believed American Indians, or Lamanites, were descendants of the people of ancient Israel, and it was the responsibility of Mormons to convert Lamanites to their religion.

Though the missionaries hoped to live peaceably among the Indians, laying out a fort was almost their first step, commenced on June 18, only the second working day after their arrival. Part of this fort still stands at Las Vegas Boulevard and Washington Avenue. The location is three miles from Big Springs, but here Las Vegas Creek flowed down a hillside, allowing for a small water-powered mill.

An uprising in central Utah in 1853 prompted Young to advise that forts be built in all new settlements, and as many as 35 were accordingly built by Mormons.

The one in Las Vegas was large and well-designed by frontier standards, and those who saw it in its heyday wondered how farmers and missionaries came to build in such a military manner. Research by James Hinds, a Las Vegas military historian, found the probable answer. Steele, the fort’s designer, had served in the Mormon Battalion during the Mexican War. The war carried him to Pueblo, in what is now Colorado, where he presumably had the chance to study nearby Bent’s Fort, built by traders. Irish born, Steele also had lived in Scotland, where he would have had other opportunities to view fortifications.

The main material for the fort was adobe brick, made on the spot. Foundations were stone. Walls were 14 feet high, 2 feet thick for the first 8 feet of height, and a foot thick above that. The fort’s east wall doubled as the wall of “mess houses,” or dwellings for families or groups of men who shared cooking and housekeeping chores. These were built inside the fort and faced out into the courtyard. Hinds found the messes were two stories high, and suggests the first floor must have been made of dirt and the second of rough wood planks. Wood was used sparingly, for the closest timber lay many miles away in the Spring Mountains. Nails also were in short supply, so rawhide thongs or wooden pegs would have been used to attach the planks to beams.

There were holes in the wall for shooting at attackers, and two corners of the fort had bastions, protruding structures from which defenders might fire along the walls.

Garden plots and farmland were apportioned to each man, and the fields were fenced with branches of thorny mesquite. The missionaries planted “grain of all sorts” and at first the crops grew well; in July Bringhurst remarked in a letter that the corn grew an inch and one half in 24 hours.

But the soil proved too alkaline for many crops. By October, Steele wrote to a friend, “I planted three acres of corn, oats, peas, beans etc., and my oats came up most beautiful; and so did everything else, but … the saleratus killed it, and I will not have three bushels of corn on it.”

Relations with the Indians began auspiciously. In July Bringhurst wrote the Deseret News, “Shortly after we arrived here, we assembled all the chiefs, and made an agreement (treaty) with them for permission to make a settlement on their lands. We agreed to treat them well, and they were to observe the same conduct towards us, and with all white men.”

The mission’s recorder, George Washington Bean, had learned the Ute tongue years before. He found the Paiute language different but could make himself understood. Bean wrote that the Indians “helped us grub the land, make adobes, attend the mason and especially to herd the stock.” The Paiutes’ favorite unit of exchange was the squash, and they didn’t expect many for a day’s work.

In the spring of 1856 the missionaries laid out a farm for the Indians, about a mile and a half north of the mission, plowed it and showed the Indians how to plant it. Trying to teach Paiutes to farm was not culturally hopeless, as some have depicted. Paiutes to the northeast had been farming at least 80 years.

The missionaries, however, found they could not grow enough food to feed themselves and all the Paiutes. Colonists estimated at least 1,000 Indians lived in the Las Vegas Valley or near it; there were never more than 103 members of the Las Vegas Mission, and some of those were children too young to work.

In the fall of 1856 the mission was 4,000 to 5,000 pounds short of the amount of flour required to sustain it until the next harvest. Bringhurst called upon men skilled with carpenter tools to go to California and work for the flour.

That same year, some missionaries reported, a drought also hurt the Paiutes’ traditional supplies of wild foods. Thefts became a problem. In July the mission books record, “Brother Bringhurst being informed that the Lamanites had been committing serious depredation upon the grain, melons, etc., by coming into the fields in the night time, he called up chief Joshua (Patsearump, a Paiute leader who had been baptized and thus had a Christian name also) and gave him to understand that such things must be stopped immediately … Joshua pleaded his inability to govern his people when they were hungry, but his intentions were always good and friendly toward the brethren.”

In early August, at the Paiutes’ request, Mormon riflemen brought their better weapons and joined them in a hunt, but no game was found.

The mission log records: “Sunday, Aug. 17. At night the brethren were watching in the corn field and caught an Indian boy stealing corn. Several others were with him, but ran away before they could be gotten hold of. Prest. Bringhurst ordered the boy chained up in the fort all night to see if it would have a salutary influence upon him and the others.”

“Monday, Aug. 18. In the morning the chief and some of the Indians came into camp, feeling perfectly friendly. They said it was alright to punish the boy, although some wanted to retaliate upon the cattle and horses, but the chief talked peace, saying that if they did not want to be tied up they must quit stealing. The boy was released early in the morning and sent to his camp.”

An ox was driven off but recovered. A calf was killed. Tensions grew among the missionaries themselves. Steele wrote, “Things began to change. The same old-fashioned sermons was preached and arses threatened to be kicked if men did not do what was wanted of them … (I thought) that more mild treatment would do just as well.”

The discovery of lead nearby, at what is now called Mount Potosi, caused problems within the mission.

In May 1856, Nathaniel V. Jones arrived in Las Vegas bearing orders from Young himself, and claiming authority to take men from the mission to work the mines. Steele related, “Jones presented his letter of instruction to President Bringhurst and there was a great storm between them calling each other anything but gentlemen.”

Bringhurst refused to accept Jones’ authority. When food grew short, Bringhurst refused supplies to Jones’ mining party, encamped southwest of Las Vegas at the location which would later be named Potosi. He refused to send the mission blacksmith to the mines.

Jones returned to Salt Lake City to buy suitable material for an ore smelter. Returning Dec. 4, he bore a letter from Young, notifying Bringhurst that he had been “dropped from the mission and disfellowshipped from the Church.”

One week later, Bringhurst started for California.

Getting the lead out proved to be even more challenging than harvesting a corn crop. The ore proved complex, and could not be profitably mined by smelting alone, yet there was insufficient water at the site for other processes. In January 1857, the Jones group abandoned the mines. The Las Vegas missionaries were allowed to leave the mission in March, though a few remained voluntarily.

The final blow to the Mormon settlement came in the fall of 1858, when Indians who had not yet accepted the Mormons’ teachings swept down from the mountains and stole the harvest from the fields. At a special conference in Santa Clara, Utah, church officials officially abandoned the Las Vegas Mission.

Yet the mission was not such a failure as it might appear. The local Indians’ relations with whites improved immediately upon the Mormons’ arrival, and remained better, after their departure, than in much of the desert West. Las Vegas Paiutes retained their identity, and also part of their original home territory near the fort. They regained more of it in recent years, the Snow Mountain reservation.

The Mormons’ buildings and irrigation trenches, though unable to support 100 missionaries, did support ranchers who took them over later. The Mormon Fort was the seed of European-style civilization in Las Vegas.

Bringhurst would soon regain good standing in the church. He served several years as bishop of the ward at Springville, Utah, and Young selected him as one the six founding trustees for Brigham Young Academy (now Brigham Young University). He died in February 1883.

Standard directories of Utah pioneers, and a biography provided by the BYU public information office, do not mention his service at the Las Vegas Mission, though it consumed nearly two years of his life.

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full