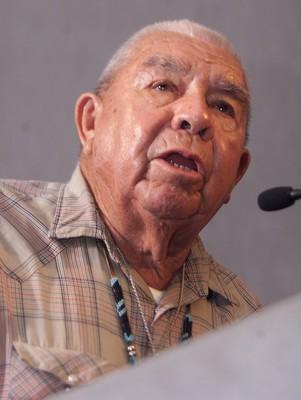

Western Shoshone leader dies at 87

For decades, Corbin Harney was a fixture at anti-nuclear rallies advocating for peace and protection of “Mother Earth,” especially his native land, Newe Sogobia, which stretched across a wide swath of what became Nevada.

On Tuesday, Harney, spiritual leader of the Western Shoshones, died of complications from cancer in a rural area of Santa Rosa, Calif., his family and friends said. He was 87.

“We have truly lost a lot,” said his nephew, Santiago Lozada, who was at his side when died.

“He was an incredible man who touched a lot of people throughout the world and throughout the country,” Lozada said. “It was hard to stay strong.”

Julie Fishel, Harney’s friend at the Western Shoshone Defense Project, said, “Corbin passed in the way he was supposed to. He was with family and friends. He was comfortable. We had golden eagles circling this place after he passed away.”

In Lee, Nev., where friends and family members will gather for a three-day wake 22 miles south of Elko, Harney’s cousin Larson Bill recalled how “he was always out there speaking about the wrongs the government did to the Shoshone people.”

“He talked about Mother Earth, plant life, bird life, fish life. They’re all connected. The land, everything has life to it. Plants and rocks, they have a spirit,” Bill said.

“One of the things he hated to see was using the Shoshone land for testing weapons of mass destruction. He didn’t believe in that,” he said.

Bill said his cousin recently had traveled to Northern California from the Poo Ha Bah healing center Harney had founded in Tecopa, Calif.

“He went to Santa Rosa to finish up his book. … I think he pretty much knew he was going to go, but he wanted to get a lot of things done before he went,” Bill said.

Ian Zabarte, secretary of state for the Western Shoshone National Council, said Harney “was always steadfast in trying to prevent the proliferation of nuclear weapons and guard the people against the threats and hazards that nuclear technology poses.

“He did that right up to the end despite everything else,” Zabarte said.

Harney was born March 24, 1920, in Little Valley, Idaho. He spent much of his life in Nevada and was among the leaders of the anti-nuclear movement that drew thousands of protesters to Peace Camp, outside the Mercury entrance to the Nevada Test Site.

From 1986 through 1994, two years after the United States put full-scale nuclear weapons testing on hold indefinitely, at least 536 demonstrations were held at the test site involving 37,488 participants and 15,740 arrests, according to government records.

After the demonstrations, held by the American Peace Test, Harney through the Shundahai Network continued to protest the government’s continued nuclear weapons work and effort to put a repository for highly radioactive waste adjacent to the test site at Yucca Mountain, 100 miles northwest of Las Vegas.

He backed opposition to the Yucca Mountain project by Citizen Alert, a statewide environmental group, and once described the mountain as a snake that’s constantly moving. “Underneath, hot water is going to cause a lot of friction in that tunnel,” he warned in 2001.

Six years later, the Department of Energy has yet to submit a license application for the planned repository to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission though Congress approved the project over then-Gov. Kenny Guinn’s veto of it in 2002.

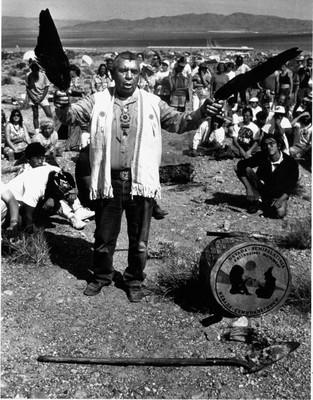

In a 1998 protest, Western Shoshones supported by hundreds of protesters erected a tepee beyond the entrance to the test site. Harney issued a statement saying the Shoshones “were put here by the creator as a native people to take care of this land and all the life on it.

“Shoshone people have taken care of this land for thousands of years,” he said. “The government has stole this land from us, and now it is very contaminated. For 50 years they have kept us out with fences and guards.”

In 2000, Harney continued to condemn the government’s actions, particularly the Department of Energy for conducting subcritical nuclear experiments at the test site, saying, “It is with blatant disrespect that the DOE continues to violate our Mother Earth as well as disregard the Treaty of Ruby Valley.”

More recently, at a public meeting in Amargosa Valley in 2005, Harney questioned the integrity of the Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed 10,000-year and 1 million-year radiation safety standards for the Yucca Mountain site, saying, “I want to know for sure if we’re going to tell the truth. We cannot be telling each other fibs.”

The truth “from the beginning,” he once said, is that “the people are going to have to wake up to the problem and get a cleaner source of power, wind or solar, that doesn’t have waste.”

Harney traveled around the world as a speaker and environmentalist. He received national and international awards and spoke before the United Nations in Geneva.

He authored two books, “The Way It Is: One Water, One Air, One Earth” and “The Nature Way,” soon to be released.

Fishel said that before Harney died, he said, “We are one people. We cannot separate ourselves now. There are many good things to be done for our people and for the world. … It is important to teach the younger generation so that things are not lost.”

The family is finalizing funeral plans, but burial services will be at Battle Mountain Indian Community, where his wife, Marge, is buried.

He is survived by his daughter, Reynaulda Taylor; two granddaughters, four grandsons; seven great-grandchildren; two great-great grandchildren; and the family of his sister, Rosie Blossom.