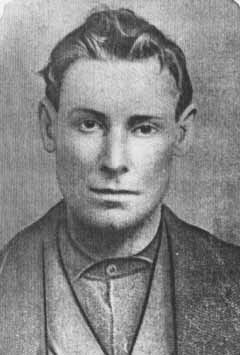

Ute Warren Perkins

When Elizabeth Whitemore of St. George, Utah, decided to move to Southern Nevada in 1880, she and her young son, Brigham, were in the vanguard of the second Mormon colonization of the Muddy River country. She was a widow. Her husband, a doctor, had been killed by Indians at Pipe Springs, Ariz., in 1866. She needed to hire a stout and fearless man to assist and protect her.

Everyone knew who was the toughest man in St. George: Ute Warren Perkins. He had demonstrated his physical prowess on many occasions. Grandson Orville Perkins told of an incident when Ute Warren encountered an Irish miner from Silver Reef who was full of whiskey-fueled ferocity. He made a loud declaration:

“I can whip any man this side of Salt Lake City,” he brayed.

Ute Warren Perkins stepped up to answer the challenge. Fists flew, facial features underwent modifications, and the men fought until both were exhausted. It was a draw. The Irishman wearily got to his feet and made another announcement:

“I can whip any man this side of Salt Lake City except Ute Perkins,” he croaked.

Whitemore purchased what is now virtually the entire Overton townsite for $4,000, then set her sturdy new hired hand, Perkins, to clearing mesquite, digging irrigation ditches, handling livestock and fending off human predators.

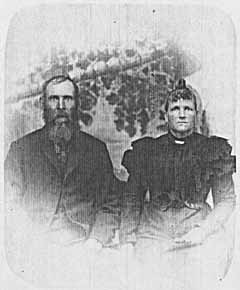

Perkins was born in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 1849. He came to Utah with his parents as an infant, and the family settled in St. George, where he later married Sarah Laub.

The Mormons had originally been called by Brigham Young to colonize the Muddy River area in 1865, as part of what was called “The Cotton Mission.” With their policy of total self-sufficiency, the missionaries had attempted to find a place where cotton would grow. They had some success in this endeavor at St. George, but the Muddy River country was at a lower altitude, hence warmer and better suited for the crop.

On Jan. 8, 1865, Thomas Smith of Davis County, Utah, was named to preside over the first settlement on the Muddy, which was named after him, St. Thomas. The first crop of settlers consisted of 11 men and three women, and within a few days that number had swelled to 45.

Living conditions were less than idyllic. The river itself, which had its headwaters at geothermal springs in the upper valley, was warm and had an unpleasant taste which sickened some settlers. Malaria and dysentery were rampant. And the constant theft of livestock taxed the patience of the Mormons, whose normal practice was to treat the Indians with respect and charity.

In 1861, Nevada became a territory, but what is now Nevada’s southern tip was then part of New Mexico Territory. In 1863, much of it became part of Arizona Territory. The Mormon settlers insisted their colony was in Utah.

In 1864, Nevada was admitted to the Union and, in 1870, commissioned a survey, which established once and for all that the Muddy River colonies were in Nevada. The state demanded that the settlers pay their taxes “in U.S. gold and silver coin,” retroactive to 1864.

It was an impossible demand. Brigham Young, who had been disgusted by the place when he had made a brief visit, sent the colonists a message:

“If the majority of the saints in council determine that it is better to leave the state whose laws and burdens are so oppressive, let it be done.” He added that it would be prudent to move as much livestock and property as possible into Utah to avoid seizure by the rapacious Nevadans.

The vote was taken, and it was nearly unanimous for abandonment.

So, in February 1871, 600 colonists packed their wagons and headed for St. George, leaving behind 150 homes, 500 acres of cleared land, about 8,000 bushels of wheat in the fields and an irrigation system valued at about $100,000. In 1881, Martha Cox was hired by the state of Nevada to be the valley’s first schoolteacher. She didn’t think much of her new posting, or her new neighbors. In her autobiography, she wrote, “The class of men who lived on the Muddy was of a low type. Old ’49ers from the California gold fields, unsuccessful prospectors … these had wandered into the valley on their way and settled down on the fields the pioneers left, and lived in their houses.”

The Pioche Record was more direct in its analysis of the valley population, describing it as “a swarm of murderers and law-breakers.”

The upper Moapa Valley had been allocated to the indigenous people, the Southern Paiute or Nuwuvi. This was done in 1873, when Maj. John Wesley Powell and G.W. Ingalls were dispatched to the area to persuade the Indians to adopt reservation life. They had farmed in the upper Moapa Valley before the advent of the white man, and were happy to take over the newly cleared farmlands they left behind. However, as usual, the government promises were empty. Whites still were allocated the best lands and the lion’s share of the water, and by 1875, they were subsisting on what water the whites would allow them, not really enough to make a living.

One of the white settlers in the area during the Mormon re-occupation, was Jack Longstreet, who came in 1882 and opened a drug store and saloon, “a combination of enterprises that promised to cure what ailed a man either one way or the other,” observed Sally Zanjani in her seminal work on Longstreet, “Jack Longstreet: Last of the Desert Frontiersmen.”

Longstreet, then in his 40s, was married to an Indian woman, spoke their language and liked to join them in their gambling games. He was known as a man quick with the gun, and with a checkered past. He is supposed to have been one of a gang of rustlers captured in Texas. His cohorts were hanged, but Longstreet, because of his youth, had one ear cropped and was sent packing. Until the end of his life, he wore his hair long to hide the rustler’s shame.

In 1883, he gave up the booze business, and homesteaded a tract of land a few miles south of the Moapa Indian Reservation.

Longstreet’s white neighbor in the upper Moapa Valley was Alexander Dry, known as a kindly fellow who would often loan one of his cows to a newly arrived family so their children could have milk, but also the author of the killing in 1878 of one John Hanley. He was exonerated, there being no witnesses.

Being a naturally quarrelsome sort, it was inevitable that Longstreet would eventually get into a disagreement with his sole neighbor. According to Orville Perkins, in his book, “Hooky Beans and Willows,” Longstreet and Dry quarrelled over water rights and the fact that the horses Dry raised had been trampling the crops of his neighbors, the Indians.

Zanjani believes there was much more to the incident. Longstreet was a passionate horse-race enthusiast and, over a period of two years, had won over $2,000 betting the ponies. However, a year later, he lost $1,000 in a race to Dry.

One afternoon, a few months later, after a few friendly rounds of tonsil wash in St. Thomas, Dry and Longstreet departed north for their ranches, apparently harboring no ill will toward each other.

As Perkins tells the story, Dry was riding alone, when a bullet knocked him from his saddle. It is supposed to have come from Longstreet’s .44 revolver. According to Perkins, Dry tried to draw his weapon, but Longstreet lunged from his hiding place and finished him off with two more shots. Longstreet claimed self-defense, which was hard to argue since Dry’s weapon was found unholstered.

On and around the land that Elizabeth Whitemore had purchased, Ute Warren Perkins had planted and rebuilt to prepare for the eventual return of the Mormons. He turned out to be a natural leader, not just because of his martial skills — which prompted Lincoln County officials to deputize him — but because of his organizational skills and capacity for hard work.

Trouble with Indians had been a serious problem during the first colonization. Despite admonitions from church leader Erastus Snow to treat the Indians well and “shoot them with biscuits,” there were occasional incidents. Perkins put an end to all of that. Perkins took the time to learn the natives’ language, and insisted that his sons do the same. He also took in an orphaned Indian boy, Jim Peters, and raised him as his own.

The second colonization was much more successful than the first. For one thing, the mines in Eldorado Canyon and Pioche were booming and the Muddy Valley farmers had a ready market for their produce and livestock. The railroads from Salt Lake City had reached Milford, Utah, only 70 miles away. Civilization was definitely moving toward the settlers, but there were still some of the old bad guys lurking about.

On one Fourth of July in St. Thomas, two of the worst of the lot got into a row that was later recalled by Orville Perkins.

A well-known rogue named Black Jack Kellett headed a gang of horse thieves who passed through the Muddy Valley about once a year. They would begin their depredations in Idaho, stealing only the finest equine specimens, driving them south at a breakneck speed to outrun the law, and stop in the Pahranagat Valley to rest and water the stock. From there, they would continue at a leisurely pace to the Muddy Valley — where they carefully avoided touching any local livestock — and then alter brands, break the broncs and otherwise prepare the animals for sale in Arizona and New Mexico.

Kellett was in town that Independence Day, as was Jack Longstreet, who got drunk and began using profane language in the presence of Mrs. Allen Gentry. Kellett demanded he apologize. Longstreet sneered. Black Jack drew his revolver, replaced it in his holster and dared the offender to draw his own weapon. Longstreet, aware that he was not at that moment in top gunfighting form, declined the offer. Black Jack noticed some small boys nearby playing marbles, and he ordered the dreaded Longstreet to get on his hands and knees and roll a marble down the street with his nose.

Kellett later moved on to California, where he shot a man over a woman and landed in San Quentin prison. He was later pardoned.

But neither Black Jack Kellett, nor Jack Longstreet nor any other outlaw misbehaved on Ute Warren Perkins’ turf. In fact, Black Jack showed up at the Perkins’ home one rainy evening when Ute was away on business and asked for food and shelter and stable space. Sarah Perkins gulped, but allowed him in, and fixed him something to eat.

As she cleared the dishes. he removed his gunbelt, took out his knife and began to pull the cartridges from his belt as Sarah watched in horror. He quietly stood each cartridge on end, then cut an X into the lead projectile, making a “dum-dum” bullet, which caused more damage to the person it struck than did a regular bullet.

“You’re afraid of me. Aren’t you, Mrs. Perkins?” Kellett said, looking up from his work.

“Yes, Jack, I am,” she trembled.

“Well, you go to bed now. I’ve done many bad things in my life, but God knows I’ve never harmed a woman, and I won’t harm you.”

When she arose the next day, the brigand was gone and three silver dollars were stacked on the kitchen table.

When Jack Longstreet left the area, it is probable that he did so because he felt sure that he would eventually get into a tangle with Ute Warren Perkins.

Ute also appreciated the need for entertainment, and he freighted the town’s first organ from Milford to Overton and was famous for organizing dances that lasted until the wee hours of the morning.

In the spring of 1903, Ute Warren Perkins was stricken with Bright’s disease, a form of kidney failure. He was taken to a hospital in Salt Lake City, where he died in April of that year. His body was brought back to Overton for burial. Sarah Perkins survived for 35 more years, and died at age 88.

In addition to making the Muddy Valley a fit and safe place for their people to reclaim, Ute Warren and Sarah Laub Perkins did their part to repopulate the valley, parenting 13 children, plus caring for the adopted Indian boy.

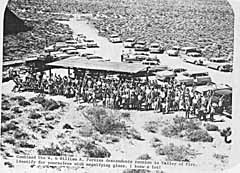

Today, the Perkins family descendants number in the hundreds, as evidenced by the enormous family reunion held in Overton in 1980, the 100th anniversary of Ute Warren Perkins’ arrival in the valley. In fact, in the old days, there was a common local saying in the Muddy Valley. “Only three kinds of people live here. White people, Indians and Perkinses.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full