Tom Williams

The early history of North Las Vegas unfolded pretty much as its founder intended that it should. Except, perhaps, for the illegal booze.

Thomas L. Williams was probably the most obscure civic patriarch in the history of any Nevada city. He died before North Las Vegas actually became a city, and seems never to have been interviewed. What is known about him comes from the people who knew him, and the occasional news item published in the Las Vegas newspapers.

But the man is not exactly a mystery, either.

He was a libertarian, though he probably wouldn’t have recognized the term. For the most part, Tom Williams thought government was a bad idea. His utopia would be free of building codes, land use regulations, laws concerning livestock, nosy cops — and people of color. The founding father of North Las Vegas was a racist.

Las Vegas had been formed overnight in May of 1905, when the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake City Railroad auctioned townsites to an enthusiastic horde of bidders.

In 1909, Las Vegas engineered a split of Lincoln County, creating Clark County.

By 1911, Las Vegas was an incorporated city with a cadre of politicians and bureaucrats, who were feverishly compiling an ever-lengthening list of dos and don’ts for the populace. Still, it was a fairly crude and rough-edged place when Williams arrived for a visit in 1917.

Whether Williams disliked Las Vegas because of its rowdiness — he was a pious, church-going man — or whether he was put off by its attempts at municipal regimentation, he decided that Las Vegas was not for him. What he did like was the valley, with its seemingly inexhaustible supply of artesian water, and potential for agricultural development.

In 1919, he moved his wife, Lola, and sons Don, Bert and Tom Jr. from Eureka, Utah, to a barren 160-acre tract about a mile down the hill from Las Vegas. He paid $8 an acre for the property.

He wasn’t the first man to attempt to establish a community in what would become North Las Vegas.

In the 1860s, Conrad Kiel had established a ranch near what is now the intersection of Carey Street and Losee Road; Kiel’s ranch had come into the hands of Las Vegas banker John S. Park by the time of the Williams’ arrival.

Peter Buol, the first mayor of Las Vegas, had drilled wells in what became the Craig Ranch and formed the Las Vegas Land and Investment Co. to interest settlers in land north of town.

But it was Williams who started an actual town. In 1919, he built his family a house, then subdivided 100 of his 160 acres, sunk a well, graded roads, extended power lines a mile down the hill from Las Vegas, and installed a system of irrigation ditches. The nucleus of Tom Williams’ town is near the current site of Jerry’s Nugget on Las Vegas Boulevard North.

The lots were offered at $10 down, which included water and power. Williams was especially eager to attract churches. Free sites were offered to any church willing to locate in the townsite. His view was that churches and church people, not civil authorities, should govern the town and keep the peace. The first house of worship was the Emanuel Church, which would become the town’s social center.

The main problem with Williams’ ideology was that it clashed head-on with a federal experiment in social engineering — the Volstead Act, which went into effect in 1919, prohibiting the manufacture, sale, possession or consumption of alcoholic beverages.

The result was that Las Vegas bootleggers, though only nominally persecuted in Las Vegas, moved their operations to the new community, which had somehow picked up the nickname of “Old Town.” There were no local laws against hooch, and no one to enforce them even if there had been.

One of the enduring legends of North Las Vegas is that of the first 80 lots sold in Williams’ subdivision, 31 were purchased by moonshiners. The founder seems to have been unaware of this, though he surely became aware of it in a hurry. But even though he was himself a teetotaler, he was not a hypocrite. As far as Tom Williams was concerned, if a man wished to make his living manufacturing liver lubricants, it was his own business.

The new cottage industry required enormous amounts of fresh grain mash. The standard cover story was that it was for livestock. If this had actually been true, the town would have had a bovine population second only to the Fort Worth stockyards. Williams stuck with legal farming but, in 1920, he seems to have unknowingly provided the moonshiners with the makings for an unusual batch of brew.

His first big crop of watermelons came in that year, but at market time, a railroad strike occurred. His good neighbors, however, saved him from ruin by purchasing the whole crop and rendered it into melonshine.

Las Vegas attorney Clifford A. Jones recalled in 1984 that when the federal agents were snooping about, Clark County Sheriff Joe Keate would race up and down the border between Las Vegas and Old Town in an open car, bellowing through a megaphone, “The feds are coming! The feds are coming!”

But what really made Old Town “Prohi-proof” was its elaborate system of tunnels, which connected the town’s numerous speakeasies, and probably a few of the major underground distilleries. The extent of the tunnel system is unknown, but former Las Vegas Police Chief Don Borax described a series of passages that was undoubtedly several miles long.

“North Las Vegas was a maze of tunnels,” he said. “But I’m not saying where they are or who built them. It was sure one wet town, though.”

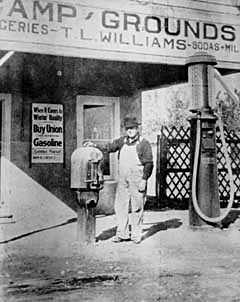

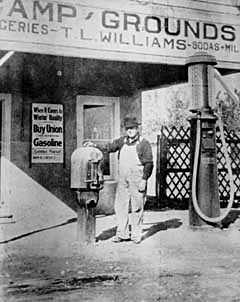

In 1924, Tom Williams built his second house, which became the town’s first business, on Las Vegas Boulevard North. (Again, near current-day Jerry’s Nugget.) It was the Oasis Auto Court, and it boasted a grocery store, campground, post office, community center — and the town’s only telephone.

There is a commonly held belief that Las Vegas was spared the full brunt of the Great Depression because it coincided with the construction of Hoover Dam.

Surely, tens of thousands of young men descended on Southern Nevada between 1928 and 1935, and a good many of them did find work at the Boulder Canyon project.

More of them didn’t, and settled down to wait for an opening. Las Vegas was intolerant toward hobos, but they were unmolested down in Old Town. An enormous squatter’s camp — a “Hooverville” — grew up on the main drag between Woodlawn Cemetery and Tonopah Avenue. The unfortunates who lived there fashioned shacks and shelters out of scrap lumber, cardboard, or mud. The richer among them owned tents. By 1932, Old Town was governed informally by a town board. It consisted of William Cohn, George Hansen, Elton Garrett and was chaired by the Rev. Albert Melton. Williams, despite his misgivings about government, also served. Of paramount importance was a school. Parents were obliged to either organize car pools and haul their kids to school in Las Vegas, or leave them to slog a mile uphill along a road with no sidewalks. The problem was solved in 1932 with the construction, on Tom Williams’ donated land, of North Las Vegas’ first grammar school, Washington School, at the corner of White Street and College Avenue. (The latter since renamed Lake Mead Boulevard.)

Then there was the sticky matter of naming of the town. Williams didn’t want it named for him. Town leaders narrowed it down to two names; North Las Vegas or Vegas Verde, which means “green meadows” in Spanish. The latter won, but only for a few months. George Hansen, who favored the North Las Vegas name, noted at one town meeting that two members who had voted for the Vegas Verde name were conveniently absent. So he brought the question to a vote once again. There was some grumbling, but he won and the name stuck.

World War II brought prosperity and growth to North Las Vegas. Nellis Air Force Base, then the Las Vegas Aerial Gunnery School, closed in 1947, but was designated as a mustering-out base for servicemen, a lot of whom settled in North Las Vegas. It re-opened in 1948 as a training facility for fighter pilots, and was generally regarded as a good neighbor even when it brought tragedy to the town.

On May 13, 1964, Lt. Raynor Hebert, a student pilot from Texas, had just taken off from Nellis when he radioed his flight leader that he couldn’t retract his nose gear, and could not gain altitude. He was high enough to bail out, but low enough to see that it was very likely that if he did so, his F-105 jet would probably strike an elementary school in its path. The school was in session. Lt. Hebert kept the crippled fighter’s nose up long enough to clear the school, and stayed with it until it came down on a row of tract homes on Lenwood Avenue, near what is now Civic Center Drive and Evans Avenue. The crash killed Hebert and four people on the ground.

North Las Vegas did not excoriate the pilot or the Air Force. Instead, it named a park for him and installed a plaque at the crash site.

In 1939, Tom Williams suffered a stroke and died.

North Las Vegas had successfully fended off several annexation attempts by the city of Las Vegas. It permanently forestalled those attempts when the city of North Las Vegas was incorporated on May 1, 1946. In the first municipal election drew 200 of the city’s 965 registered voters, and Horace Tucker edged out welder Joe Evans 185-152.

Tucker, whose successor, the late Mayor James Seastrand, would later characterize him as a “just a mean old man” served only one term.

In the early 1960s, the town began to see a serious growth boom.

The city government, under the leadership of City Manager Clay Lynch, began an aggressive and rather indiscriminate program of development. During the 1970s this included a dramatic increase in construction of federally subsidized, low-income apartment buildings. These were usually poorly built and, shoehorned onto lots originally intended for single-family dwellings, rarely had adequate parking. Population density increased, and the crime rate did, too, since the new housing generally housed the poorest of the poor. Businesses fled, banks “redlined” the city, meaning they would not make real estate loans in the city, and the leading citizens began to talk about the “image problem.”

The city expanded dramatically during the 1990s to include more “upscale” housing. and some of the more decrepit parts of Lake Mead Boulevard were spruced up.

As for that “image problem,” well, it’s just part of the city’s legacy. It was founded as a working-class town and largely remains so. The late Mayor James Seastrand, who vigorously fought the “image problem” and worked successfully to reverse the town’s downward economic trend, said in a 1988 interview: “There are those of us who live here and care for this city and would not move out of it — even though we could afford to.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full