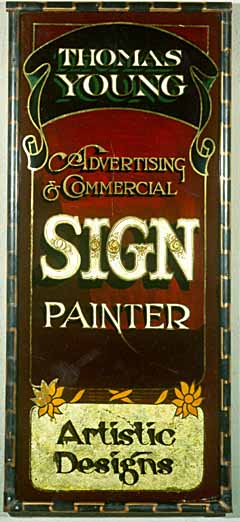

Thomas Young

It was 1931 and the guy figured the new dam would be good for business. After all, the turbines of Boulder Dam would generate more than enough electricity to light the fledgling gambling city of Las Vegas.

So, on the return from one of his road trips between his Salt Lake City home and the customers of Los Angeles, Tom Young Sr. cruised through the isolated town before returning to his family.

“They’ve just legalized gambling in Las Vegas, and we’ve got to build casino signs,” the sign maker told his wife, Elmina. “Mama, we’ve got to do that.”

For the British-born son of Mormons, it was logical, though he had qualms about profiting from the proceeds of games of chance.

“But Dad was dealing with these decent, honest people,” Tom Young Jr. remembered. “Sure they were in the gambling industry, but if they weren’t cheating, weren’t loading their dice, they were honest.”

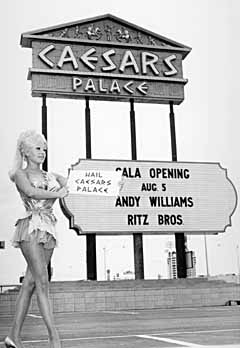

Young Sr.’s decision soon transformed his Young Electric Sign Co. into the dominant sign maker for the emerging casino industry. If Bugsy Siegel’s Flamingo was Hollywood’s playground, if the Rat Pack established the Sands as party central for Camelot-era chic, Yesco’s signs were the exclamation mark over it all.

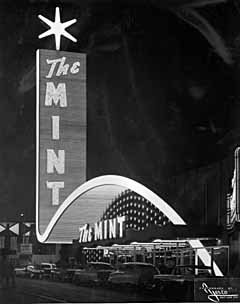

From the neon of downtown’s Golden Nugget to the multicolored lights of the Stardust, Young’s signs symbolized the 24-hour show.

“The only other place you could see neon like that was in New York City,” recounted longtime casino executive Jack Binion. “Obviously, Young was a real pioneer.”

The third of seven children, Young came to the United States in 1910 with his entire family, who settled in Ogden, Utah. A creative youngster with an entrepreneurial bent, Young grew up sketching people and animals before becoming an apprentice sign maker.

After receiving a pair of art degrees from correspondence schools, Young went to work for a sign construction company before opening Yesco in 1920 with $300. With a flair for lettering, the 25-year-old Young would take a camel-hair brush and produce sign boards that merchants would purchase for $2 down and a dollar a week.

“He found he had a way with people and could sell his product,” Young Jr. remembers.

With a slight English accent, Young Sr. carefully chose his words and knew when to flash a smile, making him the anti-Willy Loman.

“He could sell ice cubes to Eskimos,” Young Jr. says chuckling.

But he also had the 18-hour-a-day demands of running a family business, and a wife and six kids to feed during the Depression.

“Word was around, `Your dad is a wonderful guy, but I’d sure hate to be against him in a lawsuit or business deal,’ ” Young Jr. says.

Decades later, Mark Laymon offers the lament of a Vegas oldtimer. “It’s not the town it used to be,” Laymon sighs.

As the 38-year-old Yesco foreman cruises along the Las Vegas Strip, he eyes the computerized sign boards that have popped up in recent years. The MGM Grand, Monte Carlo, Bellagio, they all have them – “Tyson vs. Botha.” “Lance Burton.” “Van Gogh, Matisse, Monet.”

They’re a new generation of computer chip towers that can be rapidly reprogrammed to flash messages designed to separate casino-goers from their cash. To the out-of-towner, the multimillion dollar boards are the logical extension of the dot-com generation, where the high-tech world meets the high-risk town. Yet, Laymon remembers the very recent past.

“It used to be about neon,” he says. “It was a town known for its neon.”

True neon lighting, which relies on passing electric current through glass tubing filled with exotic gasses, is no longer common. Expert glassblowers could bend these tubes and combine them into almost any picture imaginable, and some classics of the art have been preserved in a sort of museum exhibit at the Fremont Street Experience.

Neon established Yesco’s reputation.

By 1921, his second year of operation, Young Sr. had grossed $7,400, at a time when the average monthly wage was $120. Within 10 years, his Ogden sign shop had 27 full-time workers, and was custom-bending glass tubes into the shapes of letters and trademarks and business themes.

When Young took to the road to meet with customers, he would sketch sign ideas on a hunk of wood, a paper napkin or linen. The original sign for the 1930s-era Boulder Club was sketched on a piece of butcher paper. “It was the first spectacular in Las Vegas,” Tom Young Jr. remembers.

Rather than selling his signs, the elder Young developed a program for leasing them, making them more affordable for new business owners while Yesco retained ownership of the equipment. The arrangement saw Yesco signs pop up throughout the West for banks, restaurants and hardware stores.

“Part of it,” Young Jr. says, “was we were working in the great Southwest where our customers were operating on a shoestring.”

By the end of World War II larger casinos had begun to open downtown and along the quiet stretch of highway that soon became known as “The Strip.” Owners of El Rancho Vegas, the Pioneer Club and the Las Vegas Club competed for the dollars of returning troops. The Golden Nugget joined the game in 1946; all worked with Yesco to create the biggest magnets.

“Tom and his people stood by ready to oblige,” reads a passage in “A Legacy of Light,” Yesco’s official corporate history.

A deal with Northern Nevada sign maker Dewey Laughlin also helped. The pair sliced the state in half, giving Laughlin and his QRS Neon the profitable Reno market while Young took the emerging Las Vegas territory.

They honored the commitment until 1964 when employee spinoffs from the two companies fostered the first competitive environment in Nevada’s sign making industry.

Throughout the early years, the Youngs dealt with the boys from the East, mobsters who financed the postwar Las Vegas boom with money earned from bootlegging, illegal bookmaking and prostitution.

“People would say, `You’re really in a hotbed down there,’ ” Young Jr. says, “but I can honestly say that was never apparent in our dealings.

“We had something they needed, and we were the only ones who could produce it. And they paid their bills. They were people of honor as far as we knew.”

“There was never a time some of them said, `C’mon, get in on the action.’ Besides, some of them were pretty crude, used crude language. That would turn us away quicker than any other thing. I detest crude language, and Dad did too.”

Don Lesson has been working at Yesco since the mid-1960s. An assistant manager at the company’s Las Vegas production plant, Lesson’s job description requires him to oversee service, maintenance and sign changes. As he speaks of the evolution of gaming signage, he flips through a photo album of some of his favorite work.

“I like the simple and neat,” he says, “but half the signs are not there anymore.”

He turns a few pages.

“It gives you a rush when you’re flying into Vegas and think, `There’s this one. There’s that one,’ ” he says.

To flip through the pages of Lesson’s photo album is to wander through a graphic history.

There were the combos: “Tony Orlando + Dawn.”

The ever present: “Wayne Newton.”

The one-name icons: “Dean,” and “Sinatra.”

“All of these were custom made,” Lesson says. “They are like art by themselves.”

There were the kitschy: “The Disco Party with Wolfman Jack, Peaches and Herb.”

The romantic: “Julio.”

The respect-starved: “Rodney Dangerfield.”

Sammy Davis Jr. loved his signs, and they had to be just right. If not, he’d threaten to cancel his show until the sign was fixed to his liking.

Latina bombshell Charo said hers, which included an artist’s image of her face, made her nose look like a pig’s snout.

Dangerfield loved his sign so much — it included a cartoonist’s version of his memorable visage — that one day he visited the company’s Las Vegas warehouse to ensure that it was in stock. After finding his beloved sign, the herky-jerky one stuck around long enough to shoot some hoops with the afternoon crew.

“The guys still talk about that,” Lesson says.

The ultimate Las Vegas sign may be the Fremont Street Experience, the $75 million canopy of 2 million bulbs that was opened in 1995 to lure tourists and locals to the troubled downtown casino market.

Most of the bulbs are no wider than a finger tip and generate 3 1/2 watts of light. They are covered by red, green or blue boots to throw off color.

Sixteen, though, are powerful 7,000-watt bulbs, strong enough to burn the face of a worker who stands just inches away for more than 40 seconds. After a minute the lights can leave a worker’s jacket smouldering.

Ron Ischer has been overseeing the maintenance of the Fremont Street Experience since its opening.

“Our job is monotonous because we take care of that structure every night, over and over and over,” Ischer reflects, “but it’s like show business for us. The less flaws you see, the better for us.”

The 36-year-old high school dropout did some crazy things during his younger days as a journeyman light repairman.

He’s hung over the top of buildings without a protective harness, 300 feet above the roadway, to replace one last burnt out sign bulb.

There was the time he climbed inside the old Vegas World sign in a wind storm. Perched more than 200 feet above Las Vegas Boulevard, the sign swayed four feet back and forth, as he repaired a light in Bob Stupak’s neoned signature.

With 1,050 employees at 25 offices, Yesco bills itself as the largest sign company in the country. An estimated 37 percent of its 1998 revenue came from its casino operations, a market that has expanded with the use of interior signage to lure gamblers to slot banks.

Overall, the privately held company generated 1998 revenues that were in the “high eight figures,” Young says. The company anticipates a 10 percent revenue jump for 1999.

Young Sr., who died in 1971 at the age of 76, may have unwittingly stumbled onto the formula: Use your highly visible casino signs as marketing tools for your noncasino business.

The company’s longtime policy of leasing rather than selling its signs has generated a steady revenue stream, with maintenance contracts contributing to the bottom.

“Dad would turn over in his grave if he knew the size of some of these leases,” Young Jr. says.

The company has also spawned spinoffs in a field that along with Yesco includes Mikohn Lighting & Sign, Federal Sign and Ad Art Esc of Nevada.

The son is the first to admit he’s different from his father.

“He was tougher-fisted and tougher-minded than I am,” Young Jr. says. “Verbally, businesswise, I wouldn’t say he was feisty, but if you got into a business deal with him, you didn’t push Tom Young around.

“By the time I came around I could hire people to do that for me.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full