Teacher of the Month: Be an example

Earth science teacher Megan Krier leaves her classroom once a day to meet with Western High School’s student council in a backroom that serves as a graveyard for canceled programs.

Crosscut saws and stage props are headstones for recently axed wood shop and theater programs at Western, on Bonanza Road near Decatur Boulevard. The school is among the lowest-performing high schools in the struggling Clark County School District.

The district’s 2012 graduation rate is a low 61 percent, and Western’s is lower at 54 percent. That means about one of two Western freshmen graduate four years later, according to the state’s system for calculating the rate.

Although she’s surrounded by reasons to be pessimistic, Krier is not.

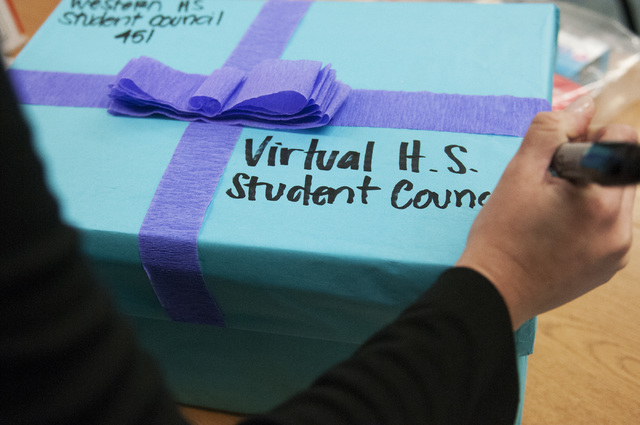

The student council meeting room is less a classroom and more a space between two garage doors where the theater department stored costumes and props. To Krier, the room was the home that the 38-member student council needed. It’s all theirs, something they didn’t have before.

And the school’s students are pure potential energy, to put it in Krier’s scientific terms.

One failing student about to accept defeat and contribute to Western’s low graduation rate said the science teacher changed her course.

“Thanks to her, I’m a senior and I’m ready to graduate,” said Elizabeth Rodriguez, who used to think graduation was out of reach. “But then came in Mrs. Krier, who talked me into coming to school every day.”

Rodriguez, who often received after-school and lunchtime help from Krier, nominated her former teacher for Clark County Educator of the Month, leading to the Western teacher being given the prize for October. Krier was chosen by a panel that includes members of the Clark County School Board, the Public Education Foundation, Teach for America and private school representatives. The Las Vegas Review-Journal sponsors the program.

All monthly winners will be honored at an end-of-the-school-year banquet, where an Educator of the Year will be named.

Krier knows the school’s stats. She came here last year despite Western’s recent designation as a “turnaround school,” meaning it has been chronically underperforming for so long that a drastic intervention and staffing changes were instituted in 2011.

But Krier sees what the school could be, as she did when looking at a room of defunct programs.

“I love Western, the students. They have such potential. They just don’t realize it. They think doors are closed to them,” Krier said.

She’s shocked when students tell her they probably couldn’t get into University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and other colleges when they actually could.

“You need to apply to Pepperdine (University). You have the grades and test scores,” she told one promising student.

She’s constantly battling what she and others in education call the “knowledge gap,” which is when students are unaware of opportunities and how to apply for college or financial aid and therefore think it’s out of reach.

The 32-year-old teacher comes from a family of educators, but it was never her idea to become one. Her mother, Jane McCoy, taught in the Clark County School District for 36 years. Grandmother Pat McNutt taught for 20 years, and her father, Jeff McCoy, taught for a few years before going the Clark County Family Services Department.

She was born and raised in Las Vegas, graduating from Cimarron-Memorial High School and then UNLV with a bachelor’s degree in environmental science and economics. Her plan was to become a lawyer, but she changed course to become a youth pastor in Paradise Valley, Ariz. That’s where she stayed for four years before coming to a realization.

“I liked doing this, teaching,” she said. “But I could impact more kids in a public school.”

She returned to Las Vegas in 2007, got her teaching license and master’s degree in teaching in 2010 and landed a job in the same school she attended, Cimarron-Memorial. There, she met her future husband, physical education teacher Tommy Krier. He transferred to Western, and she followed later at the request of Western Principal Neddy Alvarez.

In her few years, Krier has come to discover that rapport comes before all else in education. Without that, it doesn’t matter what you say to students. They won’t listen.

“If they don’t like you, or they think you don’t like them, you’re toast,” Krier said.

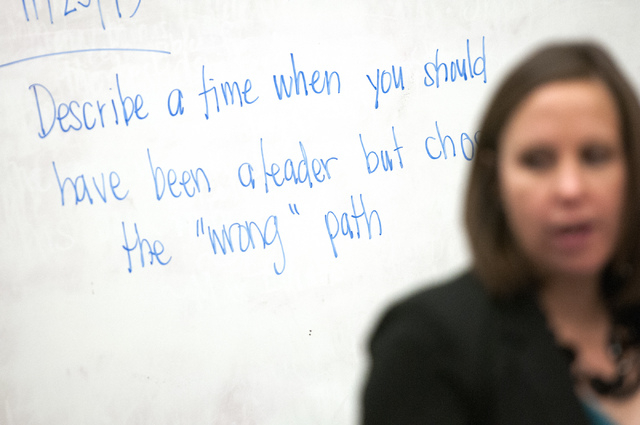

Teachers need to be an example, she said. Tell students they can do it.

“But I’m not going to coddle you through it,” Krier said Monday, shortly after the end of a class where students didn’t follow a simple instruction. She told them to place their practice quizzes on the table and move four places to their left to grade a classmate’s work. They couldn’t do it, so she told them to all sit down and explained how she was disappointed in them. They can do better. She expects better.

They all looked to her and listened quietly.

She’s a teacher. After searching for something else, she wandered back to the family profession and is glad she did.

“I love it, love it,” she said. “Ask me again in 20 years.”