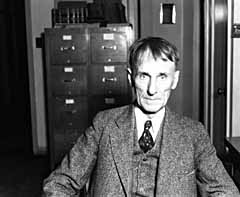

Sims Ely

On June 2, 1935, Boulder City Manager Sims Ely delivered a speech over NBC radio. Referring to Boulder City and the nearly completed Hoover Dam, Ely said “there have been manifested here in a very actual way some of the principles that have distinguished the Bureau of Reclamation … human sympathy, courage, and common sense … . The thousands of workers who soon will be leaving here will always remember Boulder City as a town of fine artistic planning and beautiful landscaping; a town of happy living conditions … where the highest American ideas were fostered.”

The idyllic life Ely describes was almost entirely his own creation, since he controlled every aspect of the city’s economy and morality.

He was “an honest, upright and thoughtful man,” wrote Ray Lyman Wilbur Jr. in his 1935 master’s thesis about Boulder City.

“He was a little Hitler,” remembered former dam worker Tex Nunley.

Ely was born Jan. 7, 1862, in Overton County, Tenn., and educated at the College of Commerce in Bloomington, Ill. He edited a newspaper in Hutchinson, Kan., and later was editor and publisher of the Arizona Republic in Phoenix.

Ely’s first link with the Boulder Canyon Project was his membership in the League of the Southwest, a private organization which promoted Western development. During a meeting in Los Angeles in April 1920, the league urged the federal government to build a dam on the Colorado River in Boulder Canyon.

Delph Carpenter of Colorado and Ely of Arizona suggested a water rights pact among the seven Colorado River states, leading to the Colorado River Compact, which made Hoover Dam possible.

In his book, “Hoover Dam: An American Adventure,” Joseph Stevens writes that Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur decided Boulder City and the Boulder Canyon Project Federal Reservation would be run by an appointed city manager. He wanted “a highly skilled administrator, an executive who was supremely self-confident but not openly arrogant, a leader combining the attributes of firmness, impartiality, and incorruptibility, an authority figure who could command total respect without being hated or feared.”

The man he chose was Ely, then 69 years old and approaching the age of mandatory retirement. As Wilbur noted in his memoirs, Ely “would have full control and would keep off the reservation those who socially misbehaved in any way. In a state as free and easy as Nevada this was important, but not always popular.”

It probably helped that Ely’s son, Northcutt, was Wilbur’s executive assistant.

Sims Ely moved to his office in Boulder City’s new Municipal Building on Feb. 29, 1932.

His power was near absolute. The police force took its orders directly from him. Ely could approve or refuse commercial and residential lease applications and through this power control competition and prices. He could have men fired and thrown off the reservation.

For all the effort to create a “model American community,” Boulder City was a dictatorship. The Bureau of Reclamation did establish a three-member advisory committee, but its members were picked by project construction engineer Walker Young and served at his pleasure. This commission advised Ely, who reported to Young. The commission had no authority to override decisions by Ely or Young, its meetings were private and it stopped keeping minutes after the first few.

As Wilbur Jr., son of the secretary of Interior, wrote, “It is true that by his actions Mr. Ely gradually became a very powerful influence in the community and could make rules as he pleased, but he was always subject to his superiors. However, the construction engineer (Walker Young), the commissioner (of Reclamation, Dr. Elwood Mead), and the secretary (of the Interior, Ray Lyman Wilbur Sr.) backed him up in all his major decisions and activities … .”

A case could be made for such iron-fisted control.

“A lot of your construction stiffs, they lived by their own rules,” said Floyd Jenne, who worked for Ely as a Boulder City ranger. “If they disagreed, they went out and hashed it out. And if they disagreed with you, why, they either beat hell out of you or you beat hell out of them. That was just the way it worked. In a construction town (with families) you couldn’t have that kind of a set-up.”

Mary Ann Merrill remembered that Ely “was fair in a lot of ways but he had his own ideas and he put them into practice. And you had to go by his rules. He thought of it as his town. I’ve heard that said so many times: This is Sims’ town.”

Boulder City was built in part so the government could keep liquor, gambling and prostitution away from its workers. Cars were stopped at the reservation gate near Railroad Pass and searched for liquor. If liquor was found, the car was impounded and the guilty individuals banned from the reservation. There were no exceptions, even after Prohibition was repealed in 1933.

On Dec. 28, 1932, Ely issued this broadside:

“In the interest of the workers here, it should be understood by everybody that to be drunk on the Boulder Canyon Project Federal Reservation means expulsion from the reservation with consequent loss of job. It is unfortunate that some of the men working here have very short memories concerning the terrible conditions of unemployment which prevail elsewhere. Within a short time after getting their jobs they forget all about the privations, hardships, and despair they underwent before they secured employment, and they proceed to ‘blow’ their money with bootleggers and toss away the jobs for which they have waited so long. If the workers on this reservation cannot refrain from getting drunk they must step aside for the sober men who are anxious for employment on this work. It is a matter of choosing between drink and the job.”

Liquor sales were not legalized in Boulder City until 1969. And that spectre Ely raised in his broadside of the Big Bad World Outside haunts Boulder City to this day and often influences its civic decisions and legislation.

The enthusiasm with which Ely enforced anti-liquor and anti-gaming laws contributed to Las Vegas’ growth. Construction workers with money burning holes in their pockets found their way to the bars and brothels of downtown Las Vegas, as well as those that lined the road to Boulder City.

Another way Ely made sure vice didn’t find its way into Boulder City was through his minute investigation of applications for business permits. Ely granted leases and permits “on the basis of personal, financial and service fitness, and on training and experience.”

One applicant for a taxi-dance hall assured Ely that his dancers would be “respectable girls on salary.” Unconvinced these respectable girls wouldn’t really be hookers, Ely refused the application. Ely revoked a permit for a cab service when he discovered owner Frank Gotwalls had arranged to deliver customers from Boulder City to the Railroad Pass Casino on the road to Las Vegas, and the casino paid the fare. To this day, gambling and prostitution are made illegal in Boulder City through deed restrictions.

Ely’s control of the business permit system also kept Boulder City from becoming a typical boom-and-bust Western town. Ely often refused to grant a business permit if, in his opinion, there was no chance “of success for their venture.”

Despite flying in the face of traditional American free enterprise, the system worked. As Ely reported in August 1932, “(T)here has been no business failure … and all establishments are doing fairly well. They, of course, are not doing so well as they would like, but all are probably doing better than they would do anywhere else just now … .”

Ely was appointed superintendent of the Boulder City grammar schools, selected the teachers, and supervised administration, until Clark County took responsibility in 1933. Ely also enforced school rules and punished “antisocial” behavior among pupils. A form letter he composed to send home to parents of truant youngsters read, “Certain pupils enrolled in the Boulder City schools are creating an intolerable evil in school control by absenting themselves without leave … . The bad example thus set has a demoralizing influence on pupils of studious habits and better impulses.”

And it was Sims Ely and Boulder City businesswoman Ida Browder who established the town’s municipal library. They prevailed upon the Library of Congress to donate 3,000 discarded volumes. Ely’s involvement didn’t end there. Carl Merrill had several overdue library books he’d been unable to return when his shift was changed at the dam. “I got a call from Sims Ely about these books,” Merrill said, “and I had to go up and see him and pay the fine to him.”

Ely was particularly concerned with family matters and didn’t hesitate to punish a worker who mistreated his family. “If a man beat up his wife,” said Mary Eaton, “he’d lose his job. Sims Ely would say, ‘You just get off the reservation and don’t ever come back.’ ”

In another incident, Ely actually took a child away from her family for her own safety. “There was a girl who lived down the street from us,” remembered Lida Buck. “Her stepfather drank and she was afraid of him … Her mother drank, too — neither of them was worth a hoot. One night (she) came up to our house in her nightie and didn’t want to go home. I let her stay the night and called Sims the next day.” Ely told Buck to keep the girl and she would get paid to care for her. The girl’s parents were run out of town and the Bucks raised the girl for several years. Despite Ely’s promise, Buck added, “I never got a cent for it.”

Boulder City was more at the mercy of Sims Ely than in his care. Ely believed no one employed on the reservation had the right to keep his job just because he was a good worker. He had to abide by Ely’s unwritten rules.

Nadean Voss’ first husband, Dave Laughery, nearly lost his ranger job because he wanted to invest in real estate. “When we wanted to buy one of the fourplex apartments over on Avenue B,” Voss recalled, “Sims didn’t want us to, and he threatened to fire my husband if he did.”

Macie Felts remembers that Ely threatened to have her husband fired from his job as an electrician on the dam if he went ahead with his plans to build a house in Boulder out of native rock.

The only plausible explanation for Ely’s discouraging buying or building houses in Boulder City is that most of Boulder City was supposed to be demolished when the dam was finished. But that didn’t happen, and many people missed out on property ownership because of Sims Ely’s orders.

Ely often ordered landlords to lower their rent. Since the landlords were subleasing property they had leased from the government, Ely could control them. “Nobody in the world could live up to the terms of those leases,” Jenne said. “You could find any number of little things you could cancel a lease for. So Sims would say, ‘$40 a month’s the most you can charge for this house.’ ”

There were times when Ely seemed to exercise his power merely for the sake of letting everyone know he was the law. He lived in a house on Utah Street across from the government park where there was a tennis court, and just beyond lay Smith’s Root Beer Stand, both of which were popular with Boulder City’s teen-agers. Ely liked to go to bed early and often called out the rangers to send everyone in the park or at the root beer stand home so he could sleep. Sometimes Ely would stalk out of his house and cross the street to send the kids home himself. “He had this cap on and his gown — he looked just like the Ku Klux Klan,” recalled Eileen Conners, who was a teen-ager then.

There was also an element of racism in some of Ely’s threats. Bob Parker relates that at Boulder City’s popular Green Hut restaurant, “Clarence Newlin (hired) … a black cook by the name of McKinley Sayles. Somebody went to Sims Ely and told him that Clarence Newlin had a black cook … and that there oughtn’t to be any blacks in Boulder City. Sims Ely took it upon himself to tell (Newlin) he had to get rid of his black cook.” Newlin refused and Ely’s appeal to Washington went nowhere.

It was one of the rare instances in which Ely failed to impose his will. There was an appeal process for those who felt Sims Ely had been unfair. But Wilbur Jr., wrote that, “Young had uniformly sustained Mr. Ely so that practice of appealing (is) seldom attempted.”

Appeals and complaints were seldom attempted for another reason. “Letters criticizing Ely were intercepted by someone in the government,” said Erma Godbey. “Ely would find out who wrote the letters then make their life miserable and nothing was ever done about it.”

Ely retained his position and his power for nearly 10 years after the Hoover administration that appointed him disappeared into history.

Ely finally retired on April 16, 1941, when he was 79. The Bureau of Reclamation’s Director of Power retained control of Boulder City until 1960, but abolished the position of city manager and ran it through a city administrative officer, who had nowhere near the sweeping powers Sims Ely had wielded. Today Boulder City’s government is headed by a city manager, but one with conventional powers.

Ely went on to write a book about the Lost Dutchman Mine. He died in a Rockville, Md., sanitarium in 1954 at age 92.

When Ely retired, Bureau of Reclamation Commissioner John Page paid tribute to him in a speech at the Boulder Dam Hotel. “The conscientious attention to detail exercised by Mr. Ely in his position of city manager of Boulder City will be greatly missed,” Page said. “It was this quality plus Mr. Ely’s firmness of purpose in carrying out his difficult duties that no doubt gave Boulder City the reputation of being a model government town.”

Don Belding was more typical of the Boulder City resident. He remembered being in a local tavern one evening after Ely retired. A prominent Boulder businessman was lamenting Ely’s absence.

“He’d had things almost his own way when his friend Ely controlled the permit system and Boulder City,” Belding said. “And now he wasn’t getting his way and he was upset. I wanted to knock him in the head.”

Part I: The Early Years

Part II: Resort Rising

Part III: A City In Full